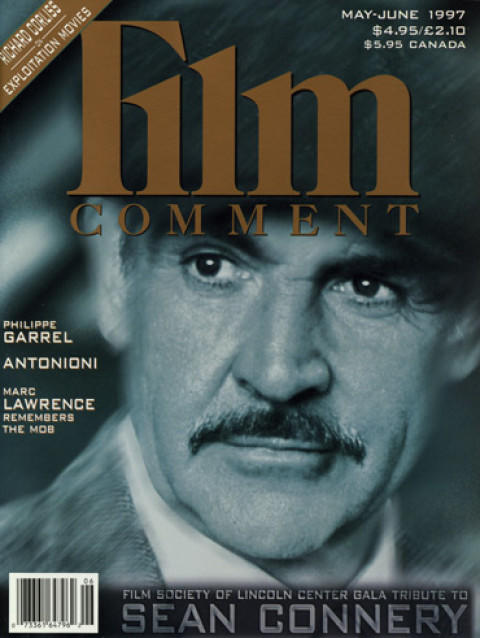

The Man Who Would be King: Sean Connery

Just back from the Crusades after twenty years, Sean Connery’s Robin Hood peers up at an abbey window to espy his onetime Maid Marian (Audrey Hepburn) decked out in nun's habit. “What,” demands her scruffy swain, “are you doing in that costume?” “Living it,” she retorts. In Robin and Marian, Richard Lester’s superb deconstruction of sustaining, fatal legend, Robin is a player past his prime, so taken by his own heroic mask he would choose to die under its weight. In fashioning one of his finest performances, Sean Connery must have called upon something of his own struggle with a devouring fiction, the near-loss of his own face to a single fixed expression of heroism.

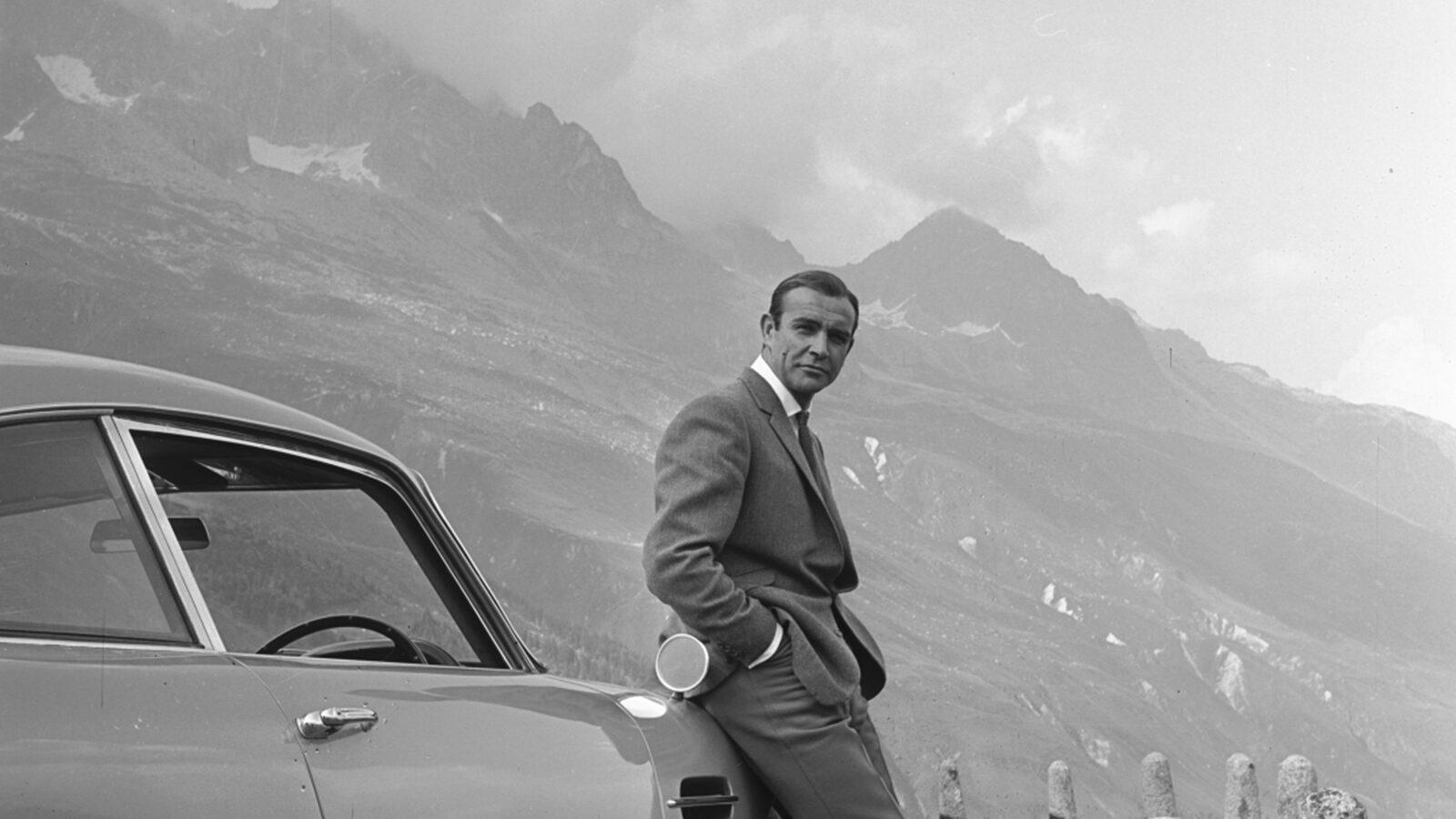

In forty years of filmmaking, Sean Connery has climbed into a remarkable variety of cinematic costume: suits from Savile Row, uniforms of every stripe, American West gear, exotic regalia from loincloth to kilt to Spanish grandee’s piratical splendor, the robes of a Benedictine monk, the sturdy tweeds of an elderly British archaeologist, and the slightly seedy duds of a boozy publisher. He’s been spy, soldier, scientist, submarine captain, cop, poet, miner, thief, messiah, sheikh, fertility god, and dragon. No matter the clothes, period, or genre, Connery displays the sang-froid of an instinctively naturalized citizen, at home from Sekandergul to Oz.

In the business of wearing fictions, projecting assumed identities, Connery has been more creatively calculating than most about the masks he tries on. Willing, with uncommon pleasure, to expose himself body and soul, but simultaneously conserving, he keeps some core of self away from the light. Almost from the beginning, he’s taken a strong hand in shaping the way his often exotic personae look, move, and speak. Offering himself to the consuming, carnal gaze of the camera, this extraordinarily centered star has quietly chosen to “live” costumes on his own terms. The off-screen Connery is adamantly reticent, opting for self-possession and privacy. He refuses to “reveal his soul to complete strangers” or to “screw in public”—past metaphors for unhappy relations with the press.

From Russia with Love

There’s room for mystery here: it lies between mask and man, between this actor’s gift for generous—though carefully curated—exhibitionism and the guarded ground where Connery lives as privately and mundanely as can be. He applies to the dangerously seductive art of movie masquerade Jimmy Malone’s first rule of law enforcement in The Untouchables: “When your shift is over, make sure you go home alive.” After his shift, Sean Connery, near-casualty of Bondmania in his 30s and People magazine’s “sexiest man alive” at 60, shuts up shop and goes home —to longtime monogamy and the serious game of golf.

Alec Baldwin, his costar in Hunt for Red October, calls Connery “the most physically beautiful man to stand in front of a camera.” Pauline Kael remarked his absolute “confidence in himself as a man. I don’t know any man since Cary Grant that men have wanted to be so much.” Snapshots of the 22-year-old Scot as nearly nude art model and cocksure Mr. Universe contestant show the kind of easy, arrogant physicality few men can muster, even movie stars B.A. (Before Androgyny). In early films, Connery is a heated presence, oozing testosterone. As the drunken sailor who assaults Martine Carol in Action of the Tiger (57) and a truck-driver in chunky turtleneck who literally snatches up a passing woman for a dance in Hell Drivers (58), he’s all thick, dark machismo, a Caliban on the way up. (Carol suggested he should have replaced washed-out wimp Van Johnson in Action’s tough-guy lead.)

That excess of unfocussed energy is a bit much for the frame to hold; you fear Connery might bust out all over. Discovered singing—“My darling Irish girl”—and scything in Darby O’Gill’s magical outdoors, our Celtic Pan levels one grand, unthreatening grin after another at his pretty colleen. But as she skips prettily away with a parting sally, his “Aren’t you a clever girl?” has the germ of something hard and dangerous in it.

The Man Who Would Be King

Unrepressed, that tone would grow into the grating, edged nasality with which James Bond, Connery’s civilized savage, aimed his hardball double-entendres. “[He succeeded] on-screen because of the promise of force behind the smile —that’s what made the smile knowing. As a young man, especially without the ‘wink’ of his mustache, he had a hard, menacing quality. He was like Jack Dempsey in a tuxedo · his integrity as natural and quick as the grin.” Writer-critic David Thomson catches Sean—boy and man—to a T … except he’s actually pegging Clark Gable, the former “King of Hollywood” whom Connery most recalls. Particularly as young men, the two share a signature expression: Amused, they cock heavy, dark brows, accents ague and grave respectively, to up the ante of the eyes’ level, suggestive gaze. Deep furrows —vertical dimples —bracket a sensualist’s smile, variously cruel and charming. Blue-collar boys, both parlayed every kind of silver-screen roguery into gold, though Gable had only John Huston’s The Misfits to crown his later years, while even mediocre movies fail to tarnish Connery’s ever-increasing majesty.

If Huston had gotten Gable, as he had hoped, for Danny Dravot in The Man Who Would Be King, the actor might have dispensed —as deftly as Connery —the sweet charm of a confidence-man taken in by his own grift. But would he have caught Danny’s deep, natural nobility as a former British soldier and scam-artist aspiring to “civilize” Kafiristan? Connery, master of bodily signature, makes us literally see gravity weight his lighthearted “Tommy” into a second Alexander, possessed by dreams of empire and justice. And it’s hard to imagine that Gable could have achieved the brave boyishness with which Connery endows his big man’s final moments: his fears of losing the affections of his brother-in-arms (Michael Caine) allayed, another Huston player whose reach has exceeded his grasp sings his way to death, gaily cashing in his chips.

But check out 30-year-old Gable’s hardcase chauffeur—sans mustache—in William Wellman’s Night Nurse; beating up on Barbara Stanwyck, he conjures a blacker, low-class James Bond, whose license to kill is not yet sheathed in elegance. Similarly, in his sociopathic charm, brutality, and dissociation, Bond is like a great sleek wolf who’s slipped into a perfectly tailored Homo sapiens suit. But the predator’s mouth and aimed gaze give away the game. The thinner upper lip may signal good taste and control, but the lower pushes outward in sensual, animal appetite. Bond’s smirk of superiority —targeting men and women alike —can expand into a killer grin, white teeth bared, lips as avid as the skinned-back gums of a hungry beast. During his hi-tech hunts, 007’s sense of humor runs to estranging sarcasm and innuendo, private puns that mark out prey—for sex and/or death. It is the antithesis of Connery’s later twinkling wit and irony. A matter of private pleasure and public service, his seasoned smile enlarges and enlivens community.

This is just the intro to Kathleen Murphy’s career appreciation of Sean Connery. Read the whole article in our May-June 1997 issue.