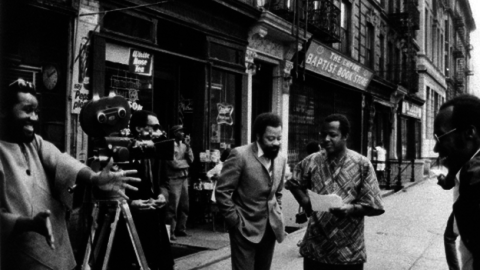

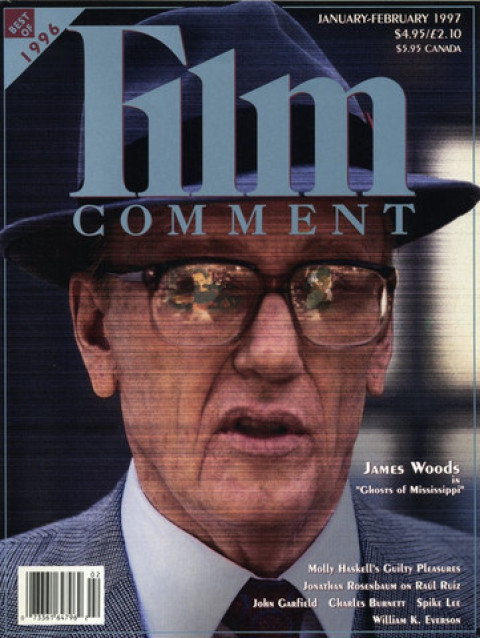

Spike Lee

The proof of Spike Lee’s insight is the clamor of opposing rash positions around his films—how difficult is it to imagine a scene from a Lee movie in which a gaggle of film critics scream their opinions about the relative worth of a young African-American filmmaker’s oeuvre in each other’s faces, shot in contrasting off-angles and perfectly sculpted light? His less sophisticated admirers, in other words those who are unwilling to apply the same sort of hardworking analysis to his work that he applies to American society, have never done him any favors by pushing him as an “innovator.” (Some innovator: his actor-on-the-dolly move, cribbed from Mean Streets and monotonously reprised in every film from Mo’ Better Blues through Girl 6, is numbingly off-key and gives the impression to the unsuspecting viewer that certain sidewalks in the New York area are equipped with conveyor belts.) Then there are those who claim that he is basically reheating old-fashioned social consciousness in a rock video microwave. But the classic social consciousness of, say, To Kill a Mockingbird begins with an abstraction—Racism, and How It Can Be Overcome—and structures its narrative accordingly: a racist malefactor and a good and righteous man square off against the backdrop of an amorphously indifferent populace that could be swayed either way and finally listens to reason. Lee, on the other hand, always starts from the specifics that make up the fractured consciousness of African-American males. “Hey daddy, I’ll suck your big black dick for two dollars!” drawls the teenaged whore to Wesley Snipes’s Flipper Purify before he screams with indignation and takes her in his arms at the end of Jungle Fever. It’s one of the few sweepingly rhetorical moments in modern cinema that earns its weight and self-importance because it’s the culmination at a whole battery of anxieties, horrors, disappointments, and subterfuges that have all been laid out by Lee with his typical block-by-block, hard plastic clarity.

There is also the overgrown-film-student charge, somewhat easier to fathom but essentially wrong and recklessly dismissive. What I understand people to mean by this is that Lee is a showoff, which is true enough. His camera never gets comfortable, and no stroll down the block is complete without at least six changes of angle. He is also constantly throwing aesthetic blankets over large chunks of his movies: changes of film stock for different locales in Clockers and Get On the Bus, high-def video for the images of the phantom callers in Girl 6, the infamous (and truly maddening) squeezed anamorphic image for the Southern section of Crooklyn. That’s not to mention the liberal application of pop songs ladled over large portions of his films. There are few filmmakers whose work seems less organic and more the sum of their aesthetic choices.

Moreover, there are few filmmakers who are less interested in (or less adept at?) giving us the rhythms of quotidian existence. The world of Spike Lee is almost completely devoid of the everyday tasks and actions that make up the backbone of most films. When he does have a go at everyday life, it is often editorialized to a level beyond absurdity. Annabella Sciorra’s family in Jungle Fever is so heavily singularized and lacking in nuance that “Italian Family” seems to be a new flavor of salad dressing. The opening scenes of Malcolm X are the most embarrassing, a fifth-hand evocation of zoot-suit culture. Lee’s relentless, never-ending control leaves you with the feeling that when his good actors (Snipes, Denzel Washington, Angela Bassett, Alfre Woodard, Giancarlo Esposito) score a few points, they’re getting one over on their director.

Mo’ Better Blues

The fact is that legibility and visibility are more important to Spike Lee than anything else. Every film has its own eye-catching design and every moment is held only as long as it takes to register as a sign; everything beyond that feels like a holding action. Lee is a completely arrhythmic filmmaker in this sense: tempo and nuance are always sacrificed for clarity. It’s fascinating to watch one of his attempts to render abandon because of his complete unwillingness to surrender his lock on the visuals. (Image and sound often seem like two separate categories with their own energies: while the visuals feel uptight, cramped, and fixated on the center, the soundtrack is always a mighty river of words and music.) When Denzel Washington’s Bleek is composing a tune in Mo’ Better Blues, Lee puts his poor actor on the dolly and spins the room around him. It’s very similar to Troy’s dream of a glue-induced flight over the block in Crooklyn because of the way that both actors are all but stapled to the camera. What is supposed to play as a sense of flight, artistic in the first instance and psychosexual in the second, is instead tidy and tight as a drum. On close inspection, though (and close inspection of Lee’s cinema is always rewarding), there’s something conceptually right about the Mo’ Better scene, since the story deals with the way that artistic expression can be the unhealthy result of a transferral of guarded aggression from mother to son, a mask of mastery to wear in a racist world.

Which is pretty close to a self-portrait, at least based on the evidence of Lee’s films (and his acting: in all of Lee’s performances his voice and his body seem to be going in two different directions, which plays like a bizarre and quite intriguing evasion technique). His detractors make an enormous leap when they lazily insist that there’s nothing but a vacuum behind all that “style.” How ridiculous: what other filmmaker has been more adept at delineating the process of American racism and treating it as a living organism rather than a frozen entity? It’s no small achievement, even when the film is as artistically pallid and mushy as School Daze or Mo’ Better Blues. The insistence on leaving nothing to chance, which often flattens out his representations of jazz clubs, city blocks, and middle-class homes to the point that they feel like computer art, has a painful, extracinematic edge. You can feel Lee’s desire to loosen up, but it’s always checked by his fear of making a move without the protection of his agile mind. His films are personal in the strangest sense: the artist is revealed by the many ways with which he chooses to constantly camouflage his personality.

The film school complaint is the other side of the coin from the more absurd charges of “reverse racism,” divisiveness, and separatism, all of which are hogwash, and all of which start from the wrongheaded assumption that Lee is some kind of “special interest” filmmaker. Aside from the fact that people are constantly attributing sentiments voiced by Lee’s warring characters to Lee himself, what’s so striking about the frequent criticisms and judgments of his work is their eagerness to reduce it to a lowest “cinematic” denominator and sweep it under the rug. The idea that Lee is a propagandist grows out of what can only be understood as fear of encroachment on the sacred territory of American cinema and its myths. It’s the same kind of fear that once prompted a friend of mine to make the following remark to an acquaintance on the neighboring barstool who said he was afraid to go to Harlem: “Let me get this straight—you’re afraid to be a white man in America?”

Jungle Fever

Lee goes against the grain of the model well-rounded filmmaker, balanced between the thematic and the organic, between action and emotion. As an artist, he has firmly positioned himself midway between didacticism and dialectics. The didactic side is his tireless effort to keep the desires, frustrations, looming terrors, and class diversity among African-American men visible and viable within mainstream, i.e. white, i.e. racist American culture. (He is less interested in women but willing to keep his films democratically open to their viewpoints, as in the interminable but informative improvised discussion in Jungle Fever.) The dialectical side is the rigorous manner in which he breaks down and presents the warring components of American society, a pot in which nothing melts and everything congeals (he has never been interested in the currently fashionable Hollywood idea of “positive images of black people,” in which Wesley Snipes or Samuel L. Jackson is afforded the same golden opportunity as Bruce Willis or Harrison Ford to play the lead in idiotic action movies). The ensuing tension, which catches characters in a grid between the personal and the societal, is palpable in every one of his films, from the throwaway Girl 6 to the hymnlike Get On the Bus, from the synthetically delicate She’s Gotta Have It to the grandiose Malcolm X, from the awful yet shaggily lovable School Daze to the magnificent Do the Right Thing and Jungle Fever. And that tension makes something odd but undeniably beautiful out of Crooklyn, an autobiographical reminiscence filtered through his sister Joie (he co-authored the script with her and brother Cinqué) that all but denies the possibility of Proustian reverie in favor of a systematic and seemingly exhaustive survey of the focal points, obsessions, and imagery of an early-Seventies African-American childhood. It’s a haunting film in which the action is interestingly dispersed across a more delicate visual palette than the burnished tones of Ernest Dickerson would have allowed (courtesy of Daughters of the Dust cinematographer Arthur Jafa), suggestive of public-school mural art.

Placing Lee as a filmmaker rather than as a public figure or a provocateur has been somewhat set aside over the years. An instructive comparison would be Claire Denis, another essentially cold and precise filmmaker intent on rendering the multicultural makeup of modern life, who also strategically casts her films in warm, convivial tones and atmospheres. Denis is also a filmmaker of choices: a handheld camera for S’en fout la mort, interlocking narratives in J’ai pas sommeil, extreme closeup sensuality spread dolloped all over Nénette et Boni. But there are moments of comfort and reflection for her characters, and none whatsoever for Lee’s—the people in his films are just as guarded and wary as their creator, who may never be relaxed enough to make a spontaneously generated autobiographical work like U.S. Go Home. A better precedent for Lee in world cinema is Nagisa Oshima, in whose films the patient accumulation of dry detail and opposing forces bursts open with an emblematic action at the film’s climax. The ending of Jungle Fever or Mookie’s garbage can in the window at the end of Do the Right Thing are kissing cousins to culminating moments like the eating of the apple in Cruel Story of Youth or the moment in Dear Summer Sister when the girl says, “They should never have given Okinawa back to the Japanese.” Oshima is a more naturally elegant and economical filmmaker than Lee—more than he would probably have cared to admit in his angrier days—but they are both children of Brecht with a shared obsession with clarity, specificity, and the abandonment of personal concerns in favor of political directness. An interesting cultural divide: where one might say that Lee “likes” all of his characters, one might in turn say that Oshima “hates” all of his, at least in early films like The Sun’s Burial (perhaps it’s more correct to say that he equalizes them to a uniform unpleasantness). In any case, the net effect is virtually identical.

Lee may be even bleaker than his relentlessly tough Japanese cousin. There is always a lot of high spirits, Fifties-style sentimentality, and verbal jazz in Lee’s work. But they hide what is in the end a despairing vision of existence, in which the backdrop of divisiveness and polarization not only never gives way to transcendent action and understanding (the way it does with the kiss at the end of Oshima’s Merry Christmas, Mr. Lawrence) but shadows his characters mercilessly. When it’s not felt in the restless visuals or through the neurotically inert characters—Lee’s people, like Fassbinder’s, are forever making small, tightly circumscribed movements across a limited selection of folkways that make them look like rats in a maze—it’s there in the oppressively heavy atmosphere, a side effect of turning every field of action (Morehouse College, a movieish jazz club located in some unimaginably bland netherworld, the life of Malcolm X, a project courtyard, a Brooklyn block) into a metaphorically charged space. There’s an uncharacteristic moment in Jungle Fever when Lee suddenly cuts to Flipper standing on a bad corner of Harlem a split second before he consorts with some unsavory characters in search of his crackhead brother (Samuel L. Jackson). You can feel his tension, distaste, and angry confusion in the way he mills around, his body tight. It’s an unusual moment because it hands over the reigns to an actor, no matter how short the duration. The entire Harlem-swanky-architectural-firm-Bensonhurst social grid that Lee has set up seems to be pressing down on Flipper.

Malcolm X

There are appalling things in Jungle Fever, but it remains his most devastating film, perhaps for the crazy reason that it’s the one most packed with interlocking thematic material. That’s the paradox of Lee as an artist: the more linear and streamlined his films are, the duller they get and the more they flounder. The Tim Robbins-Brad Dourif yuppie tag team, the Italian family scenes (Anthony Quinn’s performance as a supposedly prototypical Italian father—“Your mother was a real woman!”—is like an industrial disaster in an olive oil factory), the floating conversations between Lee and Snipes all just sit there, but their place in the grid that Lee sets up, the way they counterpoint, amplify, and bruise one another, give the film a remarkable fullness and social three-dimensionality. As in Do the Right Thing (which has some similarly awful moments that are nonetheless vital cogs in the machinery, like Lee and Turturro’s conversation about niggers), Lee achieves something rare in American cinema, which is an illustration of the degree to which people are products of their environment, a far cry from the bogus individualism of so much American cinema. Flipper and Angie (Sciorra) are ciphers at the center of Jungle Fever, surrounded by a range of far more vivid characters: Ossie Davis’s terrifyingly stern, separatist, Old Testament father and Ruby Dee’s pathologically genteel mother, John Turturro’s haloed candy store proprietor, and Samuel L. Jackson’s horrifying crackhead. And on reflection what seems like an artistic miscalculation turns out to be a dialectical strategy. Lee is speaking to middle-class people like Flipper (and himself, presumably) who keep things status quo by avoiding the cacophony of warring voices in their ears, just as in Do the Right Thing he is speaking to layabouts like Mookie who try to float through the world and eventually act out of sheer psychic exhaustion. When Mookie throws that garbage can through the window, he is egged on by his neighborhood friends, as Jonathan Rosenbaum has correctly pointed out, but he is also making a fruitless and mindless gesture that is the result of so much heat, aggravation, and sloganeering. It seems appropriate that the characters are diminished by the confusion that makes up their world (was this the reason Wim Wenders made his insane and now legendary comment that Mookie was not enough of a hero?) and that they have no time or room to analyze calmly.

In his less successful work, the striking moments come unmoored in a sea of heady aesthetic choices. Since Lee films every moment with equal weight and at an unvarying rhythm, his hyperbolic clarity can backfire on him when the focal points are reduced in number. Clockers is an unsatisfying film because the sheer immersion technique of Richard Price’s novel is antithetical to Lee’s aesthetic strengths. If any of his films does actually follow the old social-consciousness model it’s this one, in which every character represents not a societal force but a different symbolic aspect of The Drug Problem In The Ghetto. (Lee is about as good a candidate for an in-depth study of life in the projects as Richard Attenborough.) But there are impassioned moments, particularly the montage in which a slow track away from Strike (Mekhi Phifer) playing with his trains is intercut with terrifyingly immediate shots of real crackheads scoring and getting high. There’s nothing terribly wrong with Malcolm X beyond the fact that it drains a lot of the flashfire anger and drama out of the autobiography to give us a good, sturdy, dignified tour through the subject’s life (the most striking passages of the film move with the slow and stately rhythm of Washington and Angela Bassett’s immaculately acted mutual respect). Girl 6, which seems to enter a more playful mode, devolves into nothing much by the end (although it does have one of Lee’s most physically frank moments: Isaiah Washington’s shoplifter sweet-talks ex-wife Theresa Randle into an alley and shoves her hand down his pants).

Get On the Bus marks a turning point for Lee, a move towards a valid, tempered feeling of uplift and more faith in his actors and away from so much fanatical control. Lee finds myriad ways of exploring the faces of his uniformly magnificent actors in worried contemplation, to the point where his film takes on a singing beauty and a simple closeup of the great Charles Dutton carries real weight. There have been some ridiculous things written about this buoyant, defiantly old-fashioned movie, far from a song of praise to Louis Farrakhan. The Million Man March does not take on ideological but symbolic import: the simple and joyous fact of one million African-American men congregating in one place is what motivates everyone to get on the Spotted Owl to Washington, and the feeling is echoed by the actors as they bite into their meaty roles. The makeup is standard WWII bomber crew stuff: an old failure, a young upstart actor, a gentle cop, a reformed gangbanger, a homosexual couple, a silent Muslim, a Republican businessman, an estranged father reunited with his gangbanger son and chained to him by court order, a Jewish relief driver, an aspiring filmmaker/witness (“Spike Lee Jr.,” as one of the characters calls him), and the bus driver-spokesman hash out what seems like every conflict that currently besets the African-American community in a more musical version of vintage Rod Serling or Reginald Rose. But as always, Lee short-circuits any answers beyond a lonely self-respect. There is a painfully beautiful moment midfilm when the cop, whose father has been killed by gang members and whose beat is the ghetto, listens to the murder confession of the former gangbanger-turned-counselor, a moment made possible by the fellowship of the bus ride. And the cop suddenly turns the tables and tells him he’ll have to arrest him when they get back to L.A. Lee cuts away from the standoff to a shot of the moon seen from the front window. This is presumably one of the moments in the film that’s been called a cop-out, but is it a cop-out to illustrate a hopelessly divisive issue and refuse to put a Band-Aid on it? Lee isn’t turning away from the conflict but turning towards the sad flow of time.

Do the Right Thing

Get On the Bus may be his most heartfelt movie, but it still has the protective coating of every other Lee film—its materials are just more human. As he slowly loses his audience in the increasingly foul atmosphere of corporate culture (Bus disappeared from theaters with ruthless speed), it’s puzzling to imagine how Lee will evolve. As a filmmaker he is caught between a rock and a hard place: he is too resolutely anti-American for the self-satisfaction of the current political climate, and he is too tightly coiled an artist to generate new enthusiasms now that the first flush has been over for some time. As much as I admire his abilities as a dialectician, the most penetrating moments in his enormously complex cinema are the small, instinctive ones. There is a moment at the end of Crooklyn when three of the children are walking up a public staircase, two of them holding hands and the other straggling behind, and they are lackadaisically singing a song that is gently echoed by a harmonica in Terence Blanchard’s score. When they stop they wonder what they’ll be wearing to their mother’s funeral. The heartbreak—and the moment is heartbreaking like few moments in recent cinema—is in the high oblique angle that places the kids in a vast expanse of concrete, a detail that feels as if it comes straight from the filmmaker’s memory. And it’s in the stoic trudge up the steps, the sense of a burden that must be shouldered with dignity at all costs.

And then there are two moments in Jungle Fever and Get On the Bus, almost identical. In Jungle Fever, during the crushing scene where Snipes and Sciorra are fooling around on the hood of a car, Lee makes a brief cut to a shot from the point of view of an apartment window looking down on them. We never see the inhabitant and the shot is over quickly, but once Lee cuts back to his interracial couple we just wait for the sirens to start blaring. And in Get On the Bus, amidst the guarded but real camaraderie of a Memphis bar (exemplified by a lovely moment in which Davis and the proprietor bridge their racial divide with a shared passion for rodeo, reminiscent of the scene in Powell’s A Canterbury Tale in which the Oregonian G.I. and the Kentish carpenter talk woodworking), Lee makes an almost subliminal cut to a shot of a random white face staring. We don’t see what he’s staring at, but we don’t have to. In both instances, a whole range of anger and fear is shot right into the heart of the film. It’s during moments like these that I feel another, more vulnerable Spike Lee lurking beneath the quicksilver intelligence and stoic demeanor of the one we know. The question is: does he really want to reveal himself to those staring faces and open windows, positioned throughout American culture, even in the supposedly generous world of cinephilia?