The Highest Stakes

Acouple of days after Parasite premiered at Cannes 2019, and two days before it won the Palme d’Or, I sat down for a brief interview with the film’s director, Bong Joon-ho. Parasite is the film I most wanted to see on the big screens of the festival’s main theaters, the Lumière and the Debussy, with a combined international audience of nearly 3,400. There are no truly comparable theaters in New York in terms of size, luminous projection, and clarity of sound. While movie palaces are not a necessity for art films, Bong is one of the only contemporary filmmakers whose movies appeal to both art and mass film audiences. A scathing social satire that fuses raucous comedy with deep despair, Parasite is set in contemporary Seoul, where the enormous gap between the very rich and the very poor has become as untenable as it is in many countries including our own. The indifference of the former to the desperation of the latter has horrific consequences. Bong, who seemed pleased with the film’s reception, said that for the first time he felt that he was not simply working in established genres but that he had found his own form. I agree, and so must have the jury. The decision to award the Palme to Parasite was unanimous. (Parasite will be released in the U.S. on October 11.)

The festival opened with Jim Jarmusch’s The Dead Don’t Die (currently in theaters), which is as funny and bleak as Parasite but more laid-back, until it’s not. It was both too subtle and too tough for an opening-night audience that expects straightforward cues about whether to laugh or cry—i.e., something more mainstream—and that certainly doesn’t want to be held responsible for the destruction of the planet. Jarmusch refuses to let anyone off the hook. Misplaced as it was, Jarmusch’s zombie movie set up one of the festival’s main themes—the presence of the undead, whether zombies or ghosts, in a world where late capitalism is the engine of Freud’s death drive. Atlantics, the debut feature of the French-Senegalese filmmaker and actor Mati Diop and a more lyrical ghost story, won the Grand Prix (the runner-up to the Palme). Diop, the first black woman director to be chosen for the competition, is best known as the star of Claire Denis’s 35 Shots of Rum (2008), but she has made several shorts, one of them a kind of prelude to this feature. Set in a coastal suburb of Dakar, Atlantics is a coming-of-age story in which several versions of truth compete for the heart, mind, and soul of Ada (Mama Sané), a teenage girl who is engaged to a member of the town’s ruling class but is in love with Souleiman, a poor construction worker. Ripped off by Ada’s fiancé and other exploitative Muslim businessmen, Souleiman has no choice but to attempt the dangerous voyage to Spain where he hopes to find work. Although some of Ada’s girlfriends tell her Souleiman has been lost at sea, others claim to have seen him on Ada’s aborted wedding night, when a mysterious fire erupts in what would have been the marital bed and destroys the house. Is Souleiman the arsonist or is it a djinn who has taken his form, as other djinns have possessed the bodies of women killed by sex traffickers in order to exact revenge for their deaths? Diop plays Ada’s belief in the power of love against the investigations of an earnest detective looking for a rational explanation of these inexplicable happenings. Atlantics has an oneiric beauty, punctuated throughout with realistic details of a postcolonial, patriarchal Senegalese society. In interviews, Diop invoked “the Muslim imaginary,” which involves not only the power of ghosts but of the natural world: the sun, the moon, the wind, and the tides. The attention paid to them accounts for the film’s seductive beauty. Atlantics was the only film at Cannes that I saw twice, and I look forward to seeing it yet again.

Last year, women demanded that half the festival’s competition slots be filled by women directors by 2020. It looks unlikely that “50/50 x 20/20” will be achieved, given that of the 21 competition films this year, only four were directed by women. (That’s only one more than in 2018.) But women were out in force, organizing a demonstration on the red carpet before Let It Be Law, Juan Solanas’s documentary about the current struggle for abortion rights in Argentina. It screened out of competition, as did Waad al-Kateab and Edward Watts’s For Sama, one of the most powerful films in the festival. Their first-person documentary depicts al-Kateab’s experience of living in Aleppo from 2012 to 2016, beginning with her excited participation in protests against the Bashar regime and continuing through her marriage to a young doctor who refused to leave his hospital even as the bombings by Syrian and Russian forces destroyed the city and killed tens of thousands. By then, al- Kateab’s commitment to bearing witness with her camera was as strong as her husband’s to the wounded and dying, and even after the birth of their child, to whom the film is dedicated, they stayed for months, at last fleeing to London where the film was completed. (For Sama has already aired on PBS and opens in theaters July 26.)

Papicha (Mounia Meddour, 2019)

In Un Certain Regard, the percentage of women directors was higher—close to 40 percent. Among the standouts was Mounia Meddour’s more than promising first feature Papicha, which brings fierce energy to the depiction of an 18-year-old Algerian student’s struggle to hold onto the freedom she once experienced despite the Islamic fundamentalist takeover during the civil war of the 1990s. Nedjma (Lyna Khoudri) wants to be a fashion designer, and she doesn’t want to go abroad to fulfill her dream. As the Islamists tighten their grip on the city and their deadly violence strikes home, Nedjma refuses to give up, unable to believe that her defiant staging of a fashion show inside the walls of her school could threaten her life or the lives of her friends. Meddour makes great cinematic choices, particularly the use of clothing design to specify the profound effect that the struggle between liberal and fundamentalist forces within Islam has on women. Women were killed during the civil war for not covering up, and it is quite possible that they could be again. But Meddour amps up the violence at the climax of the film, abandoning both character and narrative logic. That Papicha is imperfect doesn’t negate Meddour’s talent or the potential audience for the film. The day after the screening I overheard two young women attacking the daily press for giving such an inspiring film anything less than the highest possible rating. For all its branding as a showcase for stars and a temple of art cinema, Cannes is a market. There is an actual market that takes place largely in the basement below the big Palais theaters and in their shadow on the beachfront just behind them, where films at all stages of production from mere fantasy to fully finished work vie for financing and distribution. But every film shown in every public section of the festival is also being marketed by publicists and sales agents, and sadly, the reception of the thousands of critics and journalists who watch four or more films per day and write under extreme deadline pressure has an undue effect on whether a film, a director, or an actor will have a future or not. This year, the tendency to magnify flaws in reviewing films was epidemic. This is pure speculation, but perhaps the critics who dismissed Papicha because its director veered into action movie–style violence at the end were simply not interested in the film because they will never fear being imprisoned or shot for not wearing an abaya or a hijab.

Portrait of a Lady on Fire (Céline Sciamma, 2019)

An even more egregious carping over details was directed against one of the strongest and most moving competition films, Céline Sciamma’s Portrait of a Lady on Fire. Set in 18th-century France, it is the story of two women who fall in love, make love, and are changed forever by this brief experience. One woman is a painter (Noémie Merlant), the other is the woman she has been commissioned to paint (the great Adèle Haenel). One of the most extraordinary aspects of the film is how the passionate romance between these two characters differs from those in the many movies we’ve seen about male artists and their female subjects or muses. In those films, almost all about heterosexual liaisons, passion is always a function of unequal power; in Sciamma’s film, power (the power of the director, or the power of one or another character) is not an erotic lubricant, and that could be the reason that the depiction of sex in Portrait of a Lady on Fire is devoid of exploitation. But instead of focusing on the remarkable aspects of the film, there was a barrage of criticism among the cognoscenti based on the fact that the brushstroke technique in the painting was not correct for the 18th century. I don’t know why Sciamma made this mistake, but frankly, I just don’t care. Portrait of a Lady on Fire won the screenplay award and opens in the U.S. in December.

Beanpole (Kantemir Balagov, 2019)

If the festival didn’t come close to the 50/50 goal, it offered an usually high number of films, by both women and men directors, which (like Portrait of a Lady on Fire) centered on women. In the badly titled Beanpole (it’s the slang association with the English translation that is the problem, not the Russian title, Dylda), the second feature by the 27-year-old Russian director Kantemir Balagov (who won the directing award in Un Certain Regard), two young women survive the siege of Leningrad and the immediate aftermath of World War II because they hang onto their unlikely friendship even when it has tragic consequences. Balagov has an amazing rapport with his two nearly novice actors, Viktoria Miroshnichenko and Vasilisa Perelygina, and the beauty of his mise en scène does not diminish our comprehension of the traumas that, surely, will permanently scar his characters. (Balagov’s inspiration was Nobel Prize winner Svetlana Alexievich’s The Unwomanly Face of War.) Also in Un Certain Regard, and its Grand Prize winner, was Brazilian director Karim Aïnouz’s sprawling melodrama The Invisible Life of Eurídice Gusmão, which traces the emotional journey of a woman who searches for the sister from whom she has been mysteriously separated.

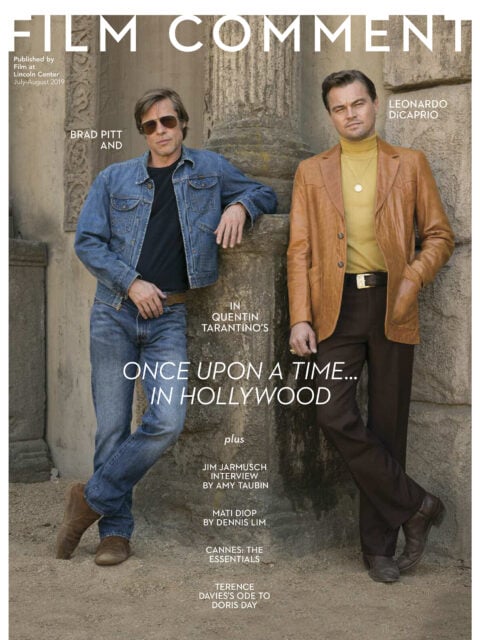

Cannes is rife with contradictions around gender, as is covering the festival, where in order to give women directors and actors their due, I’ve reinforced the binary and also neglected films I value. Thus Tommaso, the sixth collaboration between director Abel Ferrara and actor Willem Dafoe, was fascinating—no, riveting—because of the multiple male sexual anxiety and wish fulfillment subtexts dancing around the screen as Dafoe played a character too close to Ferrara for comfort, and the actors playing his wife and child were Ferrara’s actual wife and child. I was reminded of David Fincher’s remark years back about how he would love to be Brad Pitt, perhaps also because Pitt was easily the most magnetic star to walk the red carpet, and his scenes in Quentin Tarantino’s Once Upon a Time… in Hollywood brought an otherwise draggy and depressing evocation of 1969 joltingly to life. There was also a certain amount of wish fulfillment in Pedro Almodóvar’s casting of Antonio Banderas to star in his “autofiction” Pain and Glory. It’s the director’s most moving film in years, and Banderas rightfully won the male acting award. But it was Elia Suleiman, the director and star of the gravely comic It Must Be Heaven, who delivered the saddest line of the festival: “Palestine will be free, but not in my lifetime.”