The First New York Film Festival

To celebrate the upcoming 50th Anniversary of the Film Society of Lincoln Center, Film Comment will be making some classic pieces from our archive available online. This week, read Gordon Hitchens’s report on the founding edition of the New York Film Festival, featuring reviews of 1963’s most acclaimed films.

“Apart from a handful of carping critics,” stated Michael Mayer, “the event has been received with vast appreciation.” As Executive Director of the Independent Film Importers and Distributors of America, which co-sponsored the event—the New York Film Festival—Mayer has much to be proud of. The festival was a success in terms of public response and as a stimulant to increased official support for such cultural endeavors. I have no carping criticism to make, although some of the films were less than perfect. The following observations in no way detract from my vast appreciation of what was intended and of what was accomplished.

First a word about the origins of the festival: for several years there had been concern about the extent, if any, to which film would become a participant in the activities of the Lincoln Center for the Performing Arts. Cue magazine was one of many worriers about this, and there was considerable speculation in film circles regarding the possible use for film screenings of one or more of the Center’s seven auditoriums. Working with others, I obtained many signatures for a petition urging the Center to incorporate film into its activities. At that time, when policy had not yet been worked out fully, the Center took the position informally that film was not, strictly speaking, a performing art in the same sense that ballet and light opera, for example, were such. Doubtlessly, other persons and groups similarly petitioned the Center. Now, happily, such semantics are behind us, and William Schuman, President of Lincoln Center, has set the tone by his announcement that “the motion picture is an authentic art form which must be included in the presentations of Lincoln Center.” The late Eric Johnston, as President of the Motion Picture Association of America, stated that the Center’s acknowledgement of film “provides new dimension to the significance of the motion picture in the realm of culture and of art, as well as its worldwide recognition as an entertainment medium.” Heavy public attendance at the festival—more than 20,000 tickets had been sold before the first showing—vindicated the judgment of the Center’s officers. Organized by Richard Roud and coordinated by Amos Vogel, the Festival presented 20 new features in the 10-day period. At the same time, the Museum of Modern Art showed 10 features of the past decade, a program selected by Richard Griffith, Curator of the Film Library. The Festival worked in collaboration with the British Film Institute, of which Roud is Programme Director. The Philharmonic Hall films were later screened at the Seventh London Elm Festival.

The New York Festival grew of its own momentum through the efforts of the men named above, and in retrospect it now seems that the petitioners and worriers about film’s place within the Center need not have been concerned.

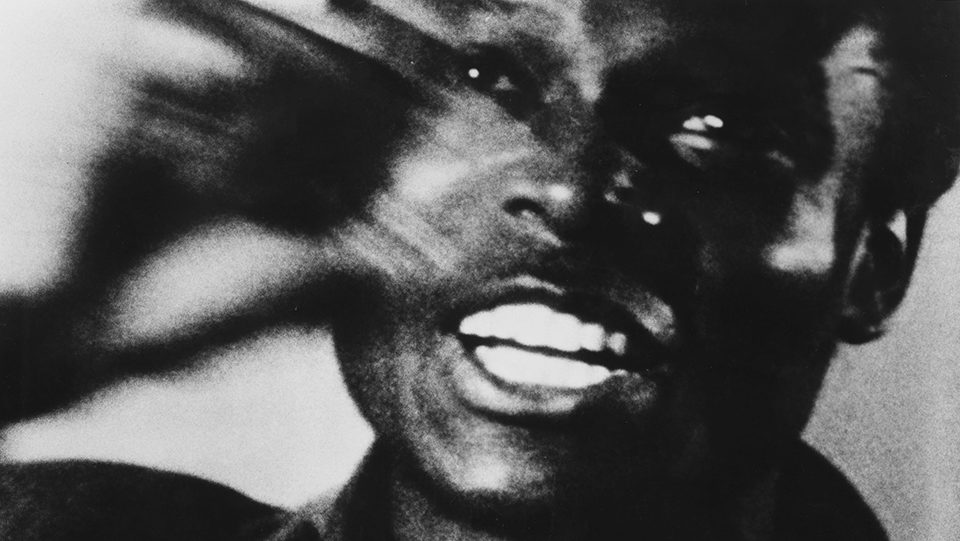

Barravento (Glauber Rocha, 1962)

Aside from the obvious applause due the festival for screening the truly excellent works, the festival is to be commended for having given exposure to those few films that have only marginal merit as art but that inform us of film concerns and methods within countries infrequently represented on American screens. Such a film is Brazil’s Barravento. Directed by 25-year-old Glauber Rocha in actual locales along Brazil’s northeast coast, Barravento concerns the Macumba cult among fishermen who barely subsist on the sea’s yield. In effect, the film is an incitement to revolution in that a supernatural tradition is seen as inadequate to fulfill man’s needs. In this film, the fishermen, descendants of African slaves, experience a challenge to their pagan faith and are confronted with the necessity to create new values for themselves. The ending is ambiguous, characteristically of its uncertain style, at one moment sure and powerful, at another moment weak and clumsy. The film’s content, however, is unmistakable: these are people who are being exploited, who suffer, who are self-deluded, but who are collectively and anonymously giving impetus to a groundswell of revolt within Latin America. The film’s title is translated as “The Turning Wind” in the festival program, and the translation is apt. The Macumbista rituals are not treated disrespectfully but rather are presented as one component of man’s nature—a capacity for irrationality. Another component is man’s capacity for protest, including destructive protest. A serious film that doesn’t fulfill altogether its intention, simultaneously personal and national, Barravento provides a good introduction to the Cinema Novo of Brazil.

The Brazilian film profits by a comparison with Argentina’s La Terraza, directed by Leopoldo Torre Nilsson, who had infinitely greater technical facilities at his disposal despite the low budgets with which he is forced to work. The Brazilian work plunges ahead crudely, finding it own style and concerning itself solely with the uniquely Brazilian way of life. The Argentine film, in contrast, seems derivative and over-calculated. Barravento has a cast of blacks, earthy and committed fundamentally to winning a livelihood from the sea; La Terraza has a cast of whites, effete and pampered; Barravento is pagan; La Terraza would reform Catholicism. Barravento’s problems, or some of them, can be solved only with social upheaval; La Terraza’s problems can be solved by tinkering with the status quo. In short: Barravento is unresolved and merciless, like life; La Terraza sentimentalizes, like fiction.

To its credit, La Terraza is a thought-provoker insofar as its puppets (never genuine people) are cleverly disposed to illustrate its theme. Three layers of age interact: (1) children, innocent but the source of social rejuvenation ; (2) corrupt youth; (3) hypocritical elders. One child is nearly killed in a fall from an apartment building, a fall caused by the war between the elders and their hard-drinking, over-sexed offspring. Unfortunately for the integrity of the film, Torre Nilsson rescues the child improbably, and she returns at the end of the film as a symbol of something like the indestructibility of good will. Meanwhile, the perpetrators of this near crime, the elders and the corrupt youth, presumably have emerged from their experience chastened. Perhaps this is as far as Torre Nilsson can go in Argentina, where bourgeois respectability lies over the land like a plague.

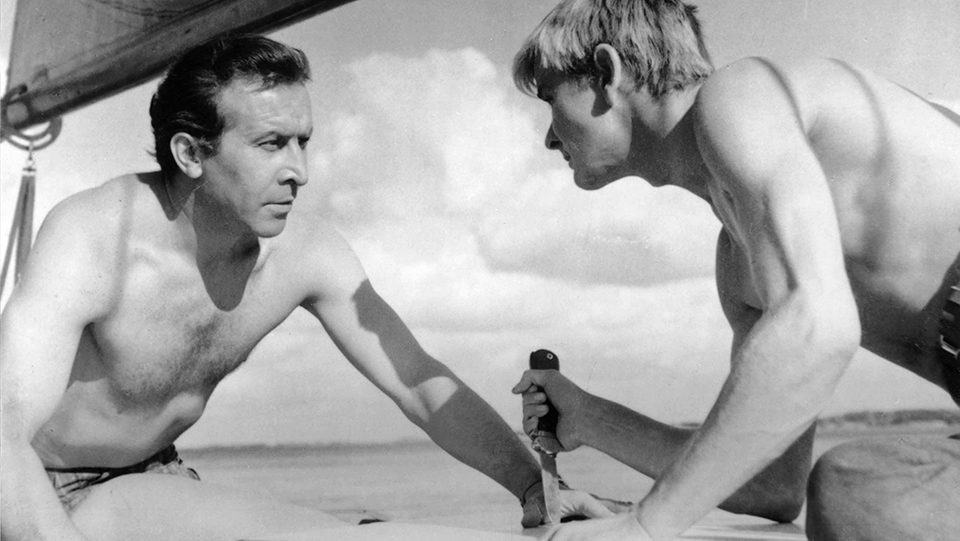

Knife In The Water (Roman Polanski, 1962)

Three films from Eastern Europe share a common basis: an indirect attack on Socialist utopia. The films are Knife in the Water, directed by the young Pole, Roman Polanski; Love in the Suburbs, by the Hungarian Tamas Fejer; and the long short, The Ceiling, from 27-year-old Vera Chytilová of Czechoslovakia. Chytilova’s first feature, About Something Else, won the principal prize at Mannheim in October. It bears certain resemblances to The Ceiling, notably the search of women for their true vocations.

Knife in the Water is too familiar by now to be discussed in detail here, and many critics have already speculated about the film’s meaning. The New York Times recently carried an interpretation by a psychiatrist to the effect that the film is a variation of the Oedipus story. As Polanski intimated during his New York visit, the film demonstrates nothing so much as the class struggle. When Polish society was reconstituted after the liberation, certain ambitious and able young men found a place for themselves, and now these men are approaching middle age surrounded by the special comforts that have accrued to people of authority within the Socialist economy. In Knife in the Water, such a man is a prosperous sports writer jealous of his hard-won possessions—a small yacht, a new car, a young wife, various gadgets accessible to better-paid Poles for the first time, and such amenities as wine with luncheon. All this is threatened, as it must be in even rigid class systems, by the younger generation. In Knife in the Water, this threat is symbolized in the figure of a vague and seemingly ineffectual young vagabond, who expresses cynicism in regard to authority, and who willingly enters the contest of wills with the older man. The young wife, in a rare moment of confidence, confesses to him that she knows of the deprivations that he and other students undergo and that she married to escape. The film, for all its superficial impression as a non-political triangle story, is actually a demonstration of certain social conflicts at work on a personal level. The two men are obsessed, each in his own way, with the assertion of power; only the woman seems truly aware of what free agency can mean, although she continues in her marriage-bargain.

Love in the Suburbs was categorized in the Philharmonic lobby under S for soap opera. Again, the film seems to be a non-political triangle story. The milieu is the suburban comfort of Hungary’s managerial class. A restless, successful engineer, unhappily married, enters the life of a young woman, herself the unhappy wife of a successful engineer. After a brief affair, the wife breaks off her relationship with both lover and husband, having found from the experience that she had been denying her true self for some years, and having determined to regain independence by resuming her old profession of weaving, a profession used in the film as emblematic of simplicity, honesty, and self-sufficiency. The wife, in rejecting the many suburban comforts and hypocrisies that marriage affords her, asserts a return to fundamentals. Too much struggle for the top, too many possessions, too much office politics, have estranged her husband from himself, so that he cannot sympathize with her wish to resume her earlier work. In flashback, the wife’s first suitor is seen, a handsome but cold Party leader who can arrange dances for factory workers but not join them.

The film’s producer, Istvan Nemeskiirthy, my co-juror at the Mannheim festival, told me that the film created a sensation in Hungary as an expose of imperfections within Hungarian society. He added that, aside from the film’s subtle thrusts at government, certain universal and permanent aspects of behavior were explored, notably one mate’s unconscious exploitation of the other. As in Knife in the Water, the husband in this film has had a long struggle to the top. The wife had worked to help him through school, and he had gone on to higher degrees, greater honors, increased position, and, finally, suburban security. And yet, what do they have? The marriage has been lost along the way. As a demonstration of certain frustrations within a Socialist nation and simply as a story of people in emotional conflict regarding their life-purpose, Love in the Suburbs lacked somewhat in dramatic urgency. Still, it was a good selection for festival goers eager to know more of Hungarian films, their themes and styles.

The Ceiling, by Chytilová, concerns an attractive young fashion model in Prague. Passive and accustomed to manipulation by profession, she is alternately drawn into one or the other of two antagonistic camps—university life among cheerful and dedicated students, versus high-fashion ladolcevita. A weakness in the film is the predictability of behavior within these two worlds. The girl reacts to it all, accepts it all, until finally she undergoes a disgusting experience from which she emerges determined to find her own values. Like the young wife in Knife in the Water, the model has reached a moment of choice, and it is her choice to resist the temptations of wealth and instead to follow the simple virtues. Chytilová’s skill redeems what otherwise might seem a naive parable. My purpose in citing the film here is principally to draw comparisons with Knife in the Water and Love in the Suburbs. All three films show a well advanced division of money, goods, and authority within the three Socialist nations concerned, and all films show unrest and frustration among the youth.

Le Joli Mai (Chris Marker, 1962)

Probably the best film of the festival was Chris Marker’s Le Joli Mai. It is described in the festival catalogue as “a record of the events in Paris of May 1962—the Salan trial, the anti-OAS demonstrations, the strikes, and the reactions of the population to these events.” Mobile of camera, inventive with sound, possessed of an eye for the abstract beauty of architectural forms, a writer of narration at once spare and stately, a bold editor juxtaposing and blending disparate sight and sound, a gentle yet unrelenting elicitor of an interviewee’s soul, a frank editorializer and symbolist, political, poetic, intellectual, tough, and left-wing Chris Marker is like nothing seen here in America before. The lobby poll showed sharp division. One famous older filmmaker was indignant—“Marker works as if there were not a long tradition of classic documentary rules.” Exactly. As Roud points out, “Le Joli Mai is one of those rare films which force one to reconsider one’s ideas of what the cinema is all about.”

Related to Marker within this sprawling family known as cinema vérité, Richard Leacock had two films at the festival—Crisis and The Chair. The latter film, on which Leacock collaborated with D.A. Pennebaker and Robert Drew, concerns the effort of attorneys to effect the commutation of death sentence, on grounds of rehabilitation of a condemned murderer, Paul Crump.

The Marker and Leacock works, customarily esteemed as respectively subjective and objective, have their starting points in reality. Leacock, a direct and unsentimental craftsman for years, is simultaneously a philosopher too intelligent and battle-scarred to be provoked by purists into a description of his works as literal representations of reality. The Chair is simply an aspect of his perception of Crump. When A is relating to B, and C (camera) enters, then all relations change, to use Leacock’s illustration. All film has at least some degree of point of view.

Because law courts and legislatures are now being filmed, because unstaged and unmanipulated film records are now common in so many areas of national life—schools, hospitals, industries, and so on—something like a quiet revolution in film technique and film ethics has been underway for years in America. One outlet for such film, of course, is television, with its unsurpassed capacity, as Garson Kanin put it, to give us the Peeping Tom vantage on formerly off-limits aspects of life. Certainly few Americans have seen a court hearing in deliberation on whether a man is to live or die, nor have many of us witnessed a turning point in law, the concession of rehabilitation as a reason for commutation of sentence.

Leacock penetrates such confines for us, and he takes us as well to the private office of Crump’s attorneys, to the prison where Crump awaits the hearing’s decision, and to the death house where the chair is being put into working order. Surely such film making, be it cinema vérité or whatever, can bring new vitality to our democracy, if used with honesty.

The exciting cinema vérité, a movement in many directions, as exemplified by two men so different as Leacock and Marker, has immense artistic possibilities as well as broad social implications. The mobility and fidelity of newly developed photographic and recording equipment used in this genre presuppose, in effect, a single man in the role of instantaneous decision-maker. This is a radical departure from the more ponderous and premeditated feature-film procedure, in which customarily a technically inexpert director dominates a hierarchy of specialists, often to the detriment of cinematic values. The new portable hardware has liberated the low-budget self-operating entrepreneurs, e.g., the Maysles Brothers: and a vigorous new style has emerged. Concerning this new, bold, and direct penetration of reality, various arguments are heard about the degree, if any, of preconception that characterizes the filmmaker. More important, perhaps, is the movement’s effect on viewers. who are discovering the events on the screen as they happen rather than receiving them prefabricated. Such footage, of course, has gone through an editor’s hands, but audiences are not ignorant to what this means, and audiences now insist on honesty—if only the filmmaker’s honesty toward his own interpretation of reality. Accordingly, cinema vérité is well established in democratic societies—France, Great Britain, and the United States—where the imperfections of society can be openly discussed. Fundamental to this genre is a belief that the public can be trusted to find its own answers.

In Leacock’s recent work—Toby, Jane, On the Pole, Primary, and others—the starting point typically has been character, the private world of a person having public significance. In these films, extensive footage on a single individual, seen and heard candidly, is edited to illuminate simultaneously his unique attributes and his universal relevance. Creating and satisfying a public appetite for personalities at once ordinary and extraordinary, these films emphasize the inadvertent self revelation of the interviewee who in some way—in politics, sports, the arts—typifies national concerns and mores. The style is distinctly public-oriented and socially committed even when most intimate and personal. The viewer’s own evaluation and judgment are elicited by the filmmaker’s effort at objectivity. The world is thus a kind of tabula rasa on which camera and recorder inscribe their own impressions. Healthfully for our free society, ideas and institutions formerly off-limits are now increasingly explored by filmmakers within cinema vérité.

Leacock and Marker have important similarities in technique and in the use of nonprofessionals in natural locales speaking their own thoughts without rehearsal or inhibition. Their dissimilarities are immediately evident, particularly in regard to Marker’s overt propagandizing. This is not to say that Marker suffers by comparison with Leacock, whose work occasionally shows a restraint that could be misinterpreted as timidity. Leacock is well known in film circles as a fire-breathing progressive, and if he refrains from scoring on the villain of a film, e.g., Crump’s prosecutor in The Chair: it is because his ethics and stylistic commitment direct him otherwise. Marker does not so inhibit himself, but instead let’s fly. In Roud’s words, “Marker, like Pontius Pilate, does not pretend to know what truth is. His truth, yes; but truth, no.” Unlike some cinema vérité filmmakers who are primarily technicians and who perhaps lack ideas and a capacity for symbolic images, Marker uses film as a means and seems to have no notion of loyalty to film as an end. He strives for verse, not prose, and, of course, workers in verse must wrench out life’s hidden essences. Accordingly, Marker constantly experiments, as his letter to me of November 4th shows: “If there is a film within the years to come, nothing at all allows me to decide if it will have any connection with the so-called cinema vérité. As a matter of fact, the odds are rather against it, because I feel more attracted by new experiments. My one and only dream in the cinematic field is to direct a very expensive science-fiction feature, with Martians, Robots, unpredictable beasts and galaxy-minded cuties. For the moment being, I have not the slightest project in film making. Le Joli Mai was an interesting experiment, but financially, I would hardly say it beats Cleopatra. Which means it may be the last of its kind, if not of my career (!?)—without much regret, because filmmaking has been for me one activity among others, and I may consider a future in photography, journalism or piano playing with total serenity.”

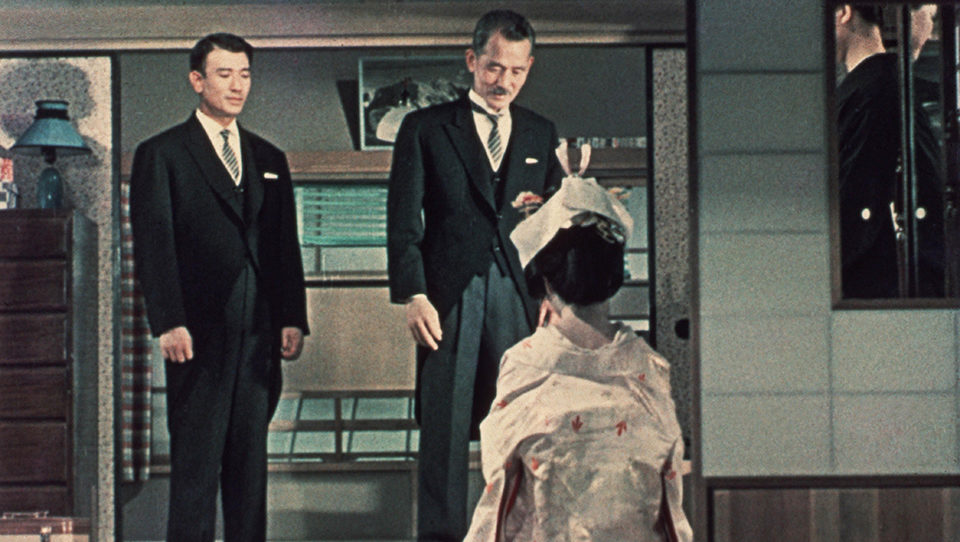

An Autumn Afternoon (Yasujiro Ozu, 1962)

Despite Marker’s good-natured pessimism, it would seem unlikely that so talented a filmmaker would long be without backing for another film, whether cinema vérité, Buck Rogers, or whatever. Among the other films of the festival, All the Way Home was a disappointment primarily because of the casting of Jean Simmons as the distraught young widow. As one lobby complainer expressed it, “When she began to suffer, I began to suffer, and that is not what Aristotle intended.” The film had a certain Americana authenticity hut seemed too obviously “a woman’s picture,” over-directed and over-controlled. Hallelujah the Hills was an instruction. More deft and daft was Baratier’s Sweet and Sour. Ozu’s An Autumn Afternoon built slowly, brick on brick, and the result was a solid edifice housing a single profound axiom: life is despair. In the Midst of Life was the only faux pas in the festival’s entire selection, technically expert but unmoving. Point of Order needs concentration but carries great impact. The film, due soon for commercial release, concerns the McCarthy-Army hearings in Washington during the final period of the Senator’s power. Cut down to 90 minutes from 188 hours of television footage, the film deserves specialized screenings in schools and civic meetings in addition to general theatrical distribution. The Olive Trees of Justice shows the directorial skill of James Blue to advantage but ultimately is weak and passive, primarily because the story cannot fulfill the existential journey of its protagonist without engaging him in the Algerian war that provides the envelope for the film. The Exiles has a strong theme—the futile search by disinherited American Indians for identification—but Kent MacKenzie keeps us waiting for something to happen instead of making it happen. Among the festival shorts, Chris Marker’s La Jetée stands out, an apocalyptic vision of post–World War III. Many other excellent shorts accompanied the features, and festival programmers showed good judgment throughout.