The Ecstatic Art

The Madonna of the Rocks is not a picture. It is a window.”

— H.D., Notes on Thought and Vision, 1919

It is a rainy day in 1925. The Imagist poet H.D. (née Hilda Doolittle) is living in a house with a group of friends in Montreux, on the shores of Lake Geneva. They decide to head into town to see a film they’re curious about, one which had been released recently in Germany: The Joyless Street, directed by G.W. Pabst. H.D. is excited to get a look at this newcomer named Greta Garbo, supposedly a great beauty. Before going into the theater, H.D. studies the poster. She notices that Garbo’s name is not blown up to signify her importance. The producer’s credit is the same font size as the names of the cast. This impresses H.D. She sits in the half-empty theater. Watching The Joyless Street, H.D. has what she describes later as her first “real revelation of the real art of the cinema.”

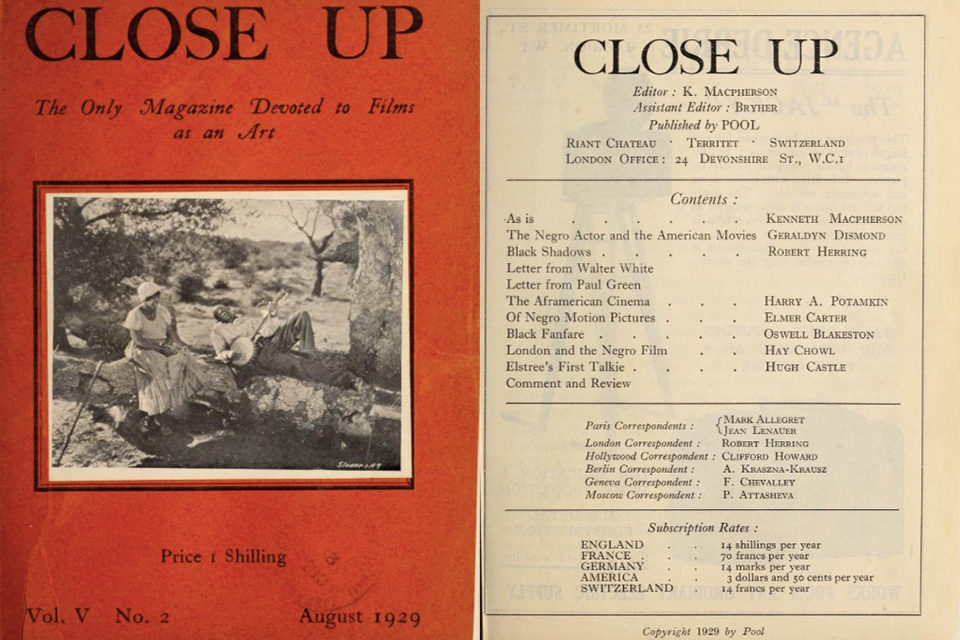

We know about this experience in such detail because she wrote about it vividly in one of her columns for the short-lived film magazine Close Up, founded by H.D., the novelist Bryher (née Annie Winifred Ellerman), and Kenneth Macpherson, a novelist, photographer, and filmmaker. The initially monthly magazine lasted from 1927 to 1933, with a steady roster of contributors from all disciplines: photographers, psychiatrists, poets. Close Up was the first journal to translate into English and publish Sergei Eisenstein’s essays on montage and cinematography, bringing Soviet films to a wider public. The magazine devoted itself to a few directors: Pabst and Eisenstein were its patron saints. H.D. wrote on Russian cinema, Conrad Veidt, Pabst’s Pandora’s Box, and, most famously—at least, it’s the only submission occasionally anthologized—an ambivalent review of Carl Dreyer’s The Passion of Joan of Arc. But it was The Joyless Street that was her measuring stick: “G.W. Pabst was and is my first recognized master of the art.”

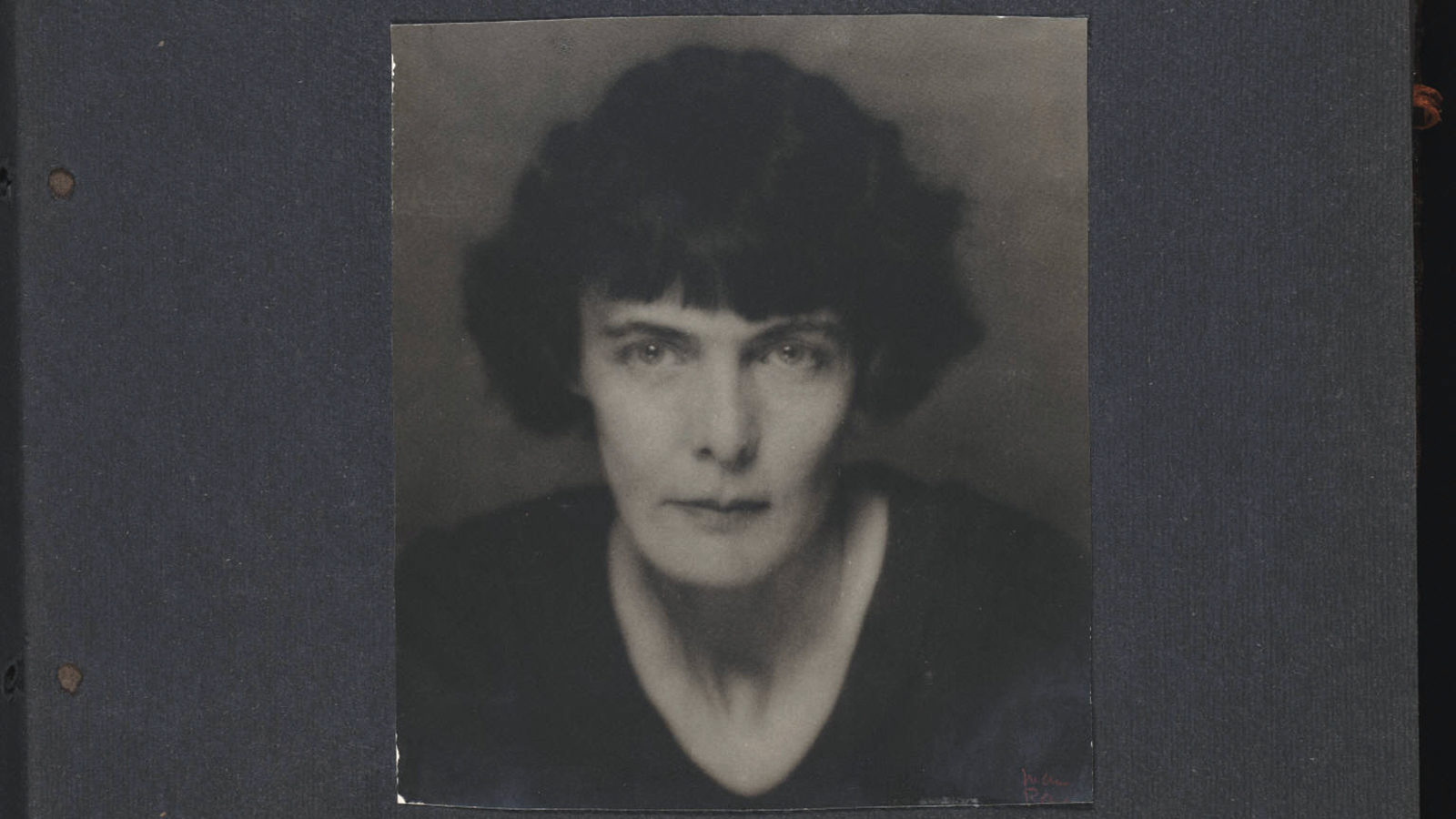

H.D. (Courtesy of the Beinecke Rare Book & Manuscript Library)

H.D. responded to cinema, as she responded to everything, passionately and personally. William Carlos Williams, a lifelong friend, described in his autobiography watching in amazement as H.D. exulted in a thunderstorm. Daughter Perdita Schaffner remembered her mother: “Her descents into everyday life were an ordeal. She over-reacted. The least disruption set off total frenzy.” That tendency is evident in H.D.’s horror at seeing the “grave, sweet creature” Garbo in the American film Torrent (1926), a year after The Joyless Street. According to H.D., what America had done to Garbo was a “vast deflowering.” In Torrent, Garbo wore “sewed-in black lashes . . . with black-dyed wig, obscuring her own nordic nimbus.” Where was Garbo’s “mermaid’s straight stare, her odd, magic quality of almost clairvoyant intensity”? H.D. wanted to rescue Garbo—whom she felt “Leonardo would have marvelled at”—from the American “Ogre” (her term for the censors who tried to sanitize her):

Let us hope [Garbo] takes it into her stupid, magic head to rise and rend those who have so defamed her. Anyhow for the present, let us be thankful that she, momentarily at least, touched the screen with her purity and glamour.

H.D.’s film writing is barely known, in either poetry or film critic circles. In Janice Robinson’s otherwise exhaustive 1982 biography of H.D., her film writing is mentioned only in a footnote. Perhaps the disappearance of her film criticism is due to the fact that Close Up had a small circulation geared to an international audience, and also that it lasted for such a short period of time (due to the development of sound films—which none of the contributors approved of—as well as Hitler’s rise to power). Could it also be that H.D.’s work has been ignored because, in general, literary critics don’t read about movies, and film critics don’t read about poetry, and so neither group paid (or pay) attention to what H.D. was doing? But H.D., as evidenced in a 1927 letter to friend Viola Jordan, had extremely strong emotions about the art form: “I feel [film] is the living art, the thing that WILL count.” Considering that H.D. was friends (and in some cases lovers) with Ezra Pound, D.H. Lawrence, Amy Lowell, and William Carlos Williams, her belief in the supremacy of cinema is striking.

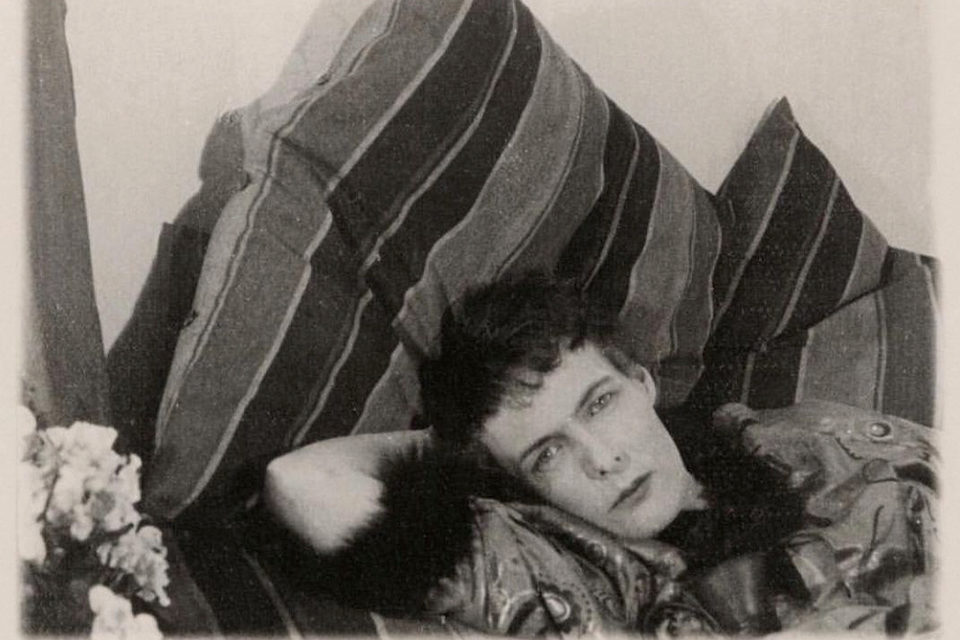

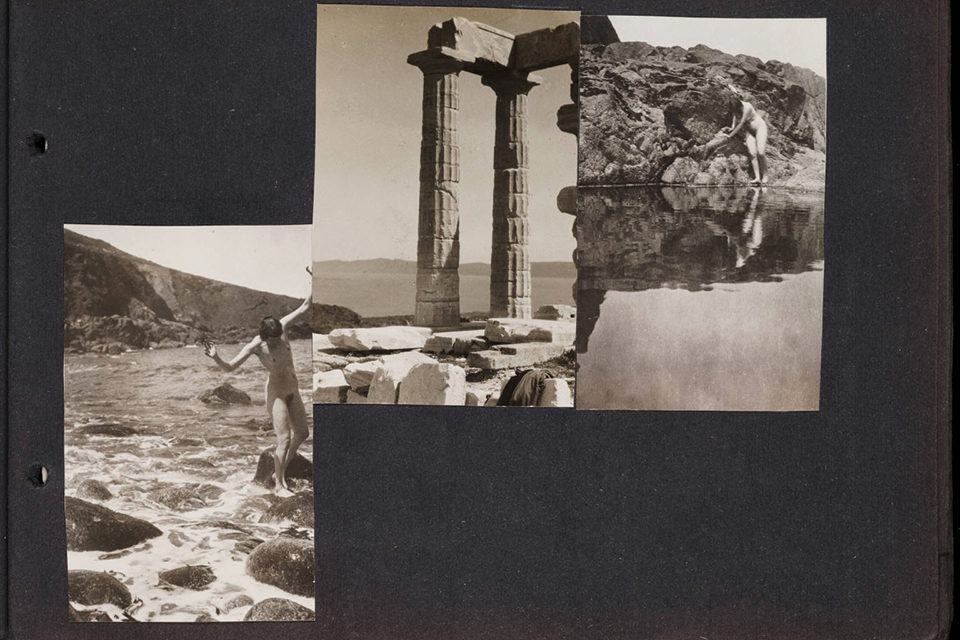

Page from H.D.'s scrapbook (Courtesy of the Beinecke Rare Book & Manuscript Library)

Born in 1886 in Bethlehem, Pennsylvania, a Moravian community outside Philadelphia, Hilda Doolittle had her first teenage romance with a young writer named Ezra Pound. In her autobiographical novel HERmione (published in 1981, long after her death), she described how “George Lowndes” (i.e., Pound) woke her up to her capabilities: “She did not know that all her life would be spent gambling with the stark rigidity of words, words that were coin; save, spend; and all the time George Lowndes with his own counter, had found her a way out.” Pound, the first person to kiss her, called her a “pink moth,” a “Greek goddess,” “Dryad.” Eventually, Doolittle’s parents raised concerns: Pound was not a proper mate for their daughter, a good girl from a religious family. (This took place decades before Pound became notorious for his fascist rantings on Italian radio during WWII, for which he was charged with treason.) In 1908, a more innocent time, Pound left for England, trailing scandal behind him. In 1911 he asked Doolittle to join him, which she did, causing a break with her parents and upbringing. Pound was a busy bee in London, trying to launch a new poetry movement he called “Imagism,” building on the ideas of poet T.E. Hulme. Imagism, one of the many opening salvos of Modernism, was a reaction against flowery Victorian-era language, against over-description, against the romanticism of the 19th century. In a lengthy “List of Don’ts,” Pound declared that, to be an Imagist, you must: “Use no superfluous word, no adjective, which does not reveal something. Go in fear of abstractions.” Doolittle, almost on a whim, went ahead and wrote her first three poems: “Priapus,” “Epigram,” and “Hermes of the Ways.” In a now famous story that H.D. tells in her 1958 journal (eventually published in 1979 as End to Torment: A Memoir of Ezra Pound), she showed these poems to Pound while sitting at their regular hangout, the tea room at the British Museum: “‘But Dryad . . . this is poetry.’ He slashed with a pencil. ‘Cut this out, shorten this line.’ . . . And he scrawled ‘H.D. Imagiste’ at the bottom of the page.”

Pound named her “H.D.” for all time in that scrawl, and nominated her as the Avatar of Imagism, which had only been an abstract idea until she came along and realized it. Her first three poems were published in Poetry magazine in the January 1913 issue, complete with “H.D. Imagiste” as a signature, and H.D. became famous. She was one of the few women on the front lines of the Modernist movement. Her first collection, Sea Garden, was published in 1916. Other volumes followed, disrupted by the cataclysm of World War I, a traumatic experience H.D. never fully recovered from (which supplied writing fodder for the rest of her life). Meeting Bryher around this time was an important event. The daughter of shipbuilder John Ellerman, she had enormous wealth. She supported H.D. financially, and it was through Bryher that H.D. met Macpherson, Bryher’s husband. It was a marriage of convenience for the lesbian Bryher, and so the three of them made a trio, living in Switzerland and dreaming up a “little magazine” about the cinema—not the cinema as it was, but the cinema as they wished it to be.

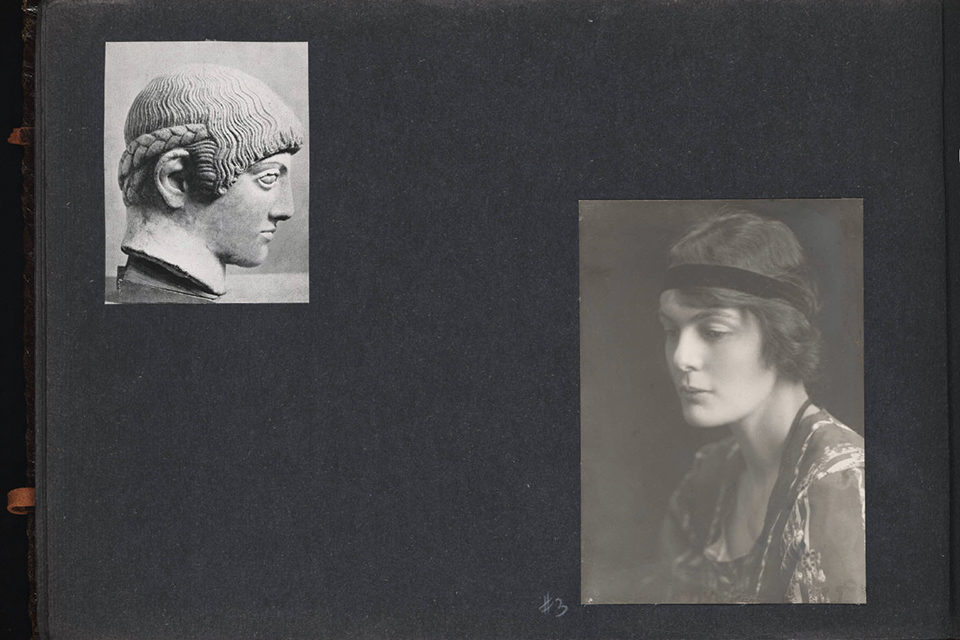

Page from H.D.'s scrapbook (Courtesy of the Beinecke Rare Book & Manuscript Library)

Yet connections to cinema predate H.D.’s involvement with her Close Up collaborators. She was always interested in different angles of seeing, of shifting perspectives, of montage, of what we would now call “dissolves.” H.D.’s poetry is so filled with references to light that in reading it, you might feel the urge to reach for sunglasses:

And the point in the spectrum

where all lights become one,

is white and white is not no-colour,

as we were told as children,

but all-colour.

Later she would write: “Light is our friend our god. Let us be worthy of it.” She eagerly bought a projector, spending “literally hours alone here in my apartment” watching images “reel past me in light and light and light.” She wrote two poems about projectors, one of which was published in Close Up. A short excerpt:

the stage is set now

for his mighty rays;

light,

light that batters gloom,

the Pythian

lifts up a fair head

in a lowly place,

he shows his splendour

in a little room;

he says to us,

be glad

and laugh,

be gay.

Close up had a mission: it would include everything and discount nothing. Long before film theory came along in the 1960s and ’70s, Close Up examined things from an intersectional standpoint. Macpherson, Bryher, and H.D. were concerned with the portrayal of race on screen, and devoted an entire issue to the “Negro in Film,” with African-American writers like Geraldyn Dismond contributing (“No true picture of American life can be drawn without the Negro,” she wrote). The Close Up creators wanted avant-garde films to be the vanguard of the new art form. They were all Modernists—artists who emerged in the 1910s and ’20s and broke away from 19th-century models. The past had died in the trenches across Europe. Cinema was thrilling because it, essentially, had no past yet: to them it was the ideal state. Writers had more of an uphill climb, and there was a Modernist version of “cancel culture,” with attempts to bring down everyone from Wordsworth to Milton. But cinema had no baggage from prior centuries. Modernists were fascinated. Virginia Woolf wrote about film; so did Gertrude Stein and Marianne Moore. James Joyce was so intrigued that he opened and (briefly) ran the Volta, the first dedicated movie theatre in Ireland. Close Up is filled with the excitement of pioneers: Dorothy Richardson, one of its contributors, wrote that film had “not yet established a code of manners.” In his regular Close Up column, Macpherson declared that he wanted to “get the medium developed so far as to be FIT for art.”

Close Up was born in the era of the “little magazine,” without which, it could be argued, the Modernist movement never would have spread. Magazines like Harriet Monroe’s Poetry (which first published H.D. and a host of luminary others, and is still up and running), The Smart Set, The Egoist, The Little Review, and W.E.B. DuBois’s The Crisis (to name a few) were essential in publishing marginalized and/or experimental voices. The same was true for film, where French film journals set the precedent for serious discussion of cinema. Le Film, Ciné pour tous, Cinémagazine, and Le Journal du ciné-club popped up throughout the 1910s and ’20s, inspiring the birth of film societies there. England’s film magazines (Cinema Quarterly, Sight & Sound, and Film Art) arrived a decade later. Close Up strolled into that crowded environment, wielding a big stick. Because Close Up was founded, in part, by two British people who despised British cinema, the magazine is unabashedly contemptuous of the culture in England. (Macpherson was particularly brutal: “The Englishman can only be roused to enthusiasm on the football field.”) The Nov. 1927 cover screams “WE WANT BETTER FILMS!!!”—not once, but twice.

Borderline (Courtesy of the Beinecke Rare Book & Manuscript Library)

Close Up was created under a larger umbrella called The Pool Group, with a book-publishing arm and a filmmaking arm. Pool put out four films, all directed by Macpherson, using the techniques he loved in the films of Pabst and Eisenstein. Of the three shorts—Wing Beat (1927), Foothills (1929), and Monkey’s Moon (1929)—only fragments remain. But Borderline (1930), their only feature, is intact. Macpherson pulled off a huge coup in getting Paul Robeson for the lead role: at that point Robeson’s only other feature was Oscar Micheaux’s Body and Soul, but he was a star in Europe, selling out concert halls. Robeson is a powerful and charismatic presence in Borderline; the only unfortunate part is that he doesn’t get to sing. Taking place in an unnamed border town in Europe, Borderline is a powder keg of race, class, and gender, reflecting the concerns of Close Up’s writers. Pete and Adah (played by Robeson and his wife, Eslanda Robeson) take rooms in an inn run by a boozy butch proprietress (Bryher). When Adah has an affair with a white man, her lover’s racist wife (H.D.) demands that the black couple be thrown out into the street. H.D. is an extremely intense figure on screen, all angles and sharp corners, with jabbing gestures filled with tension. An amateur, she fearlessly plays the ugliness and rage in this sexually repressed woman’s soul. Borderline was not received well, to put it mildly: the reviews were so dismissive that Macpherson gave up directing films altogether. Recently, there has been a renaissance of interest in Macpherson’s bold experiments with narrative and montage. In 2006, the BFI funded Borderline’s restoration, and the film was released on DVD (it’s in a Criterion Collection box set of films starring Robeson), also receiving a triumphant showing at the Tate Modern Gallery in London.

A collection of the writings in Close Up, edited by James Donald, Anne Friedberg and Laura Marcus, was published in 1998. These essays offer glimpses of cinema at the moment when it heaved itself through enormous change, as well as first reactions to films which now make up the international canon. It’s refreshing to read film criticism before it was codified into a certain accepted form and orthodoxy. Some of these pieces are wild and experimental. When “Hollywood” is mentioned in Close Up, it’s usually with derision (although there is a very entertaining interview that Bryher did with Anita Loos). H.D. sums up the collective’s lofty mission: “It is the duty of every sincere intellectual to work for the better understanding of the cinema, for the clearing of the ground, for the rescuing of this superb art, from its hide-bound conventions.”

Borderline (Courtesy of the Criterion Collection)

As the essay on Pabst and The Joyless Street shows, H.D.’s film criticism, like her poetry, is always personal. She walks you through her experience. In her review of Lev Kuleshov’s 1926 silent film By the Law (which H.D. called Expiation), she starts with a description of getting to the theater. The car could not make it up the steep street, so she walked, reveling in the sunlight. Late for the show, she snuck into the balcony. Exhilarated by the bright life outside the theater, she was jolted into another world by the film: “I felt all my preparation of the extravagantly contrasting out of doors gay little street, was almost an ironical intention, someone, something ‘intended’ that I should grasp this, that some mind should receive this series of uncanny and almost psychic sensations in order to transmute them elsewhere; in order to translate them.” She thrills to the film’s realism: “The Russian takes the human spirit acting and re-acting against human sub-strata of animal instinct, further than it can go. The spirit goes as far as the spirit can go and then it goes a little further. That is the poignant realism of Expiation.” She refers to Aleksandra Khokhlova’s performance in a series of frantic adjectives (“slip of [a] gargoyle,” “bleak young sorceress,” “vibrant,” “febrile”) until finally giving up: “there is no word for such things.” And: “Her face can be termed beautiful in the same way that dawn can be termed beautiful rising across the stench and fever of battle.”

H.D.’s most well-known essay is her cry of anguish against Dreyer’s Joan of Arc. This anguish comes from her Moravian roots, where religion was tactile and filled with ecstatic symbolism. In an inadvertent tribute to Renée Falconetti’s performance, a feeling of defiance is stirred in H.D., the cause of which she questions: “I think it is that we all have our Jeanne, each one of us in the secret great cavernous interior of the cathedral (if I may be fantastic) of the subconscious. Now another Jeanne strides in, an incomparable Jeanne, indubitably a more Jeanne-ish Jeanne than our Jeanne but it just isn’t our Jeanne.” While contemporary critics may not like this, it is an eccentric in-real-time reaction to a now-famous film in its very first release, written by one of the most famous poets of her day. It’s a danger when film criticism becomes too insular, too consensus-driven in tone and opinion. Reading her work is sometimes a shock to the senses, it’s so fresh and immediate.

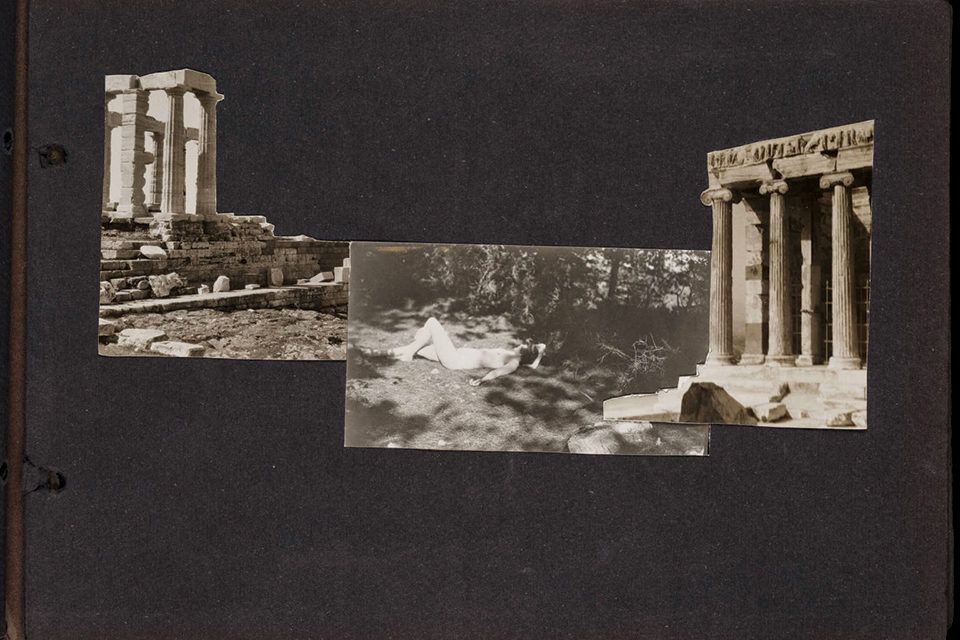

Page from H.D.'s scrapbook (Courtesy of the Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library)

In a way, H.D. is writing here about cinema’s limitations. Cinema cannot portray holiness without being corny or artificial, and H.D. believed that Joan, canonized just eight years before Dreyer’s film, was holy. H.D. writes: “Jeanne d’Arc talked openly with angels and in this square on square of Danish Protestant interior, this trial room, this torture room, this cell, there was no hint of angels . . . The Jeanne d’Arc of the incomparable Dreyer it seems to me, was kicked towards the angels.” The film upset her so much that every time she passed the theater, her hands clenched just looking at the poster. “I pay [Dreyer] my greatest compliment. His is one film among all films, to be judged differently, to be approached differently, to be viewed as a masterpiece, one of the absolute masterpieces of screen craft. Technically, artistically, dramatically, this is a masterpiece. But, but, but, but, but…”

H.D. eventually moved on from her involvement in Close Up, and the magazine also folded around that time. She went off to meet with Freud, hoping he could unpack some of the issues that had plagued her. (She wrote a book about her experience with Freud, whom she called “The Professor.” While the whole book is fascinating, it’s worth it for this sentence alone: “the Professor insisted I myself wanted to be Moses; not only did I want to be a boy but I wanted to be a hero.”) When Bryher’s father died in 1933, he left H.D. a small allowance—enough so that she could live independently for the rest of her life, which she did. She died in Zurich in 1961. Her dismay at the advent of sound was total, and as far as I can tell, she never wrote about film again. What would she have thought of Bergman, Kurosawa, Godard? Did she see any of their films? I wonder.

In one of her “projector” poems, H.D. rhapsodizes about how film allows you to enter other worlds, journey to places you will never go:

islands arise where never islands were,

crowned with the sacred palm

or odorous cedar;

waves sparkle and delight

the weary eyes

that never saw the sun fall in the sea

nor the bright Pleaiads rise.

Film is not a picture. It is a window.

Sheila O’Malley is a regular film critic for Rogerebert.com and other outlets including The Criterion Collection. Her blog is The Sheila Variations.