The Director’s Studio: Shochiku

While the script for what would become her son’s final picture, An Autumn Afternoon, was being prepared, Yasujiro Ozu’s mother died.

The year was 1962.

Still a bachelor at the age of 59, Ozu had begun his lifelong career at Shochiku Studios in the late Twenties, making capriciously modern comedies about girls and gangsters and children prone to dancing jazzy little jigs when greeting one another, or refusing adulthood altogether to remain forever (to borrow the stage name of Ozu’s favorite child star, Tokkan Kozo) like “a boy who crashes into things.” Ozu stayed so long at Shochiku that those precocious prewar comedies were eventually eclipsed by the string of Fifties “home dramas” with which he capped his career, a series of extraordinary films which match the most domesticated family matters—parents, children, marrying, aging, dying—with the most idiosyncratic of formalist memes.

For every fleeting glimpse of melancholy and evanescent intimation of mono no aware (“resignation to unchangeable things”), in those final features the director remained an eternally precocious artist at heart, busily fussing with editing patterns based on the relative sizes of sake bottles and factory smokestacks in contiguous images, or trying to get away with the elision of some climactic narrative incident that a more “mature” director would consider essential. Even today, non-Japanese audiences continue to find those radical/conservative antinomies in Ozu’s later films altogether astonishing, and rightly so. But Japanese cinema had been willing to accommodate every imaginable sort of aesthetic secret handshake and cryptic clubhouse code since its early childhood, Ozu included—even if his notorious refusal to adopt such Western commonplaces as color, or the matching of pictures with sound, was as much an act of stylish, if entirely boyish, resistance as the vow of silence taken by the pint-sized brothers in I Was Born, But… and Good Morning.

Good Morning (Yasujirō Ozu, 1959)

In so many ways, Ozu and Shochiku—which celebrates its 110th anniversary this year—were made for each other. An entertainment combine that prided itself as first and foremost a director’s studio, Shochiku had made the integration of antithetical approaches to filmmaking a company policy ever since the foundation of its Kamata studio and cinematic training school in 1924. The house specialty—a type of social realism called shomen-geki (tales of the underclass)—welcomed Stanislavski’s Method, Chaplin’s tearjerk antics, Griffith’s complex narrative cross-hatchings, and the cobwebs of Caligari’s expressionist cabinetry. There had to be parameters within which all that absorption of alien influence could function properly, however, and it fell to Shochiku’s young studio head, Shiro Kido—who would become Ozu’s lifelong supporter—to lay down the law. Kido’s ambitious plans included a Shochiku-specific formal approach to cinematic storytelling that valued the shot-by-shot construction of narrative favored by American filmmakers, and discouraged long-take, sequence-centered shooting as smacking too much of the fixed-perspective stasis and behavioral codes of kabuki and shimpa stage. He also called for a content-based value system. “We at Shochiku prefer to look at life in a warm and hopeful way,” Kido sermonized to both his audiences and his stable of young directors, which included formative masters like Heinosuke Gosho and Yasujiro Shimazu, further stipulating that “to inspire despair in our viewers would be unforgivable. The bottom line is that the basis of film must be salvation.”

And though “warm and hopeful” remained Kido’s watch-words, even movies about hookers and hoodlums were okay, as long as debts to society were properly paid and righteous paths recovered by the final fade. Hiroshi Shimizu made the most of such opportunities in his astonishing Japanese Girls at the Harbor (31), in which a Catholic schoolgirl pumps a few pistol rounds into the sorority sister she catches seducing her boyfriend in the campus chapel, serves time in prison, and ends up as a streetwalker in a geisha get-up going nowhere but down. Shimizu complied with a suitably Kido-styled happy ending, though he was clearly more interested in the moments preceding those pistol shots—when, in a hair-raising series of close, closer, CLOSE-UP! jump cuts, the girl’s seething visage lunges out of the darkness like some shadow-dwelling wraith from a long-forgotten prequel to The Ring.

Shimizu’s fondness for letting his camera follow along with his forever-perambulating characters was matched only by his pioneering love for location shooting. Even as Japan’s wartime government began to bring the pressure for propaganda to bear on Shochiku’s productions, Shimizu still found ways to wander well wide of unwanted edicts, as when his barely repressed disgust with what he regarded as artistically crippling political interference resurfaced as the central dramatic event of his 1941 classic, Ornamental Hairpin, in which a wounded and limping Chisu Ryu struggles to regain his sure and steady walk. Shimizu somehow got away with all those strolling sequence shots, but it’s astonishing that Kenji Mizoguchi, whose penchant for equating the persistence of tradition with languorous and uninterrupted long takes began at Nikkatsu Studios and ended at Daiei, could ever have felt comfortable under Kido’s control. But then, perseverance was one of Mizoguchi’s pet perversions, and he pressed it for all that it was worth in Shochiku’s government-conscripted version of The Loyal 47 Ronin (43). Submerging his Chushingura adaptation’s militarist mandate beneath some four hours of the most gloriously glacial tracking shots ever filmed, Mizoguchi—as enamored of obviated omissions as Ozu was adoring of the elided big event —decided to simply wink away the warlords when he relegated the most famous samurai showdown in Japanese literature to a cinematic status so lowly and peripheral that it transpires entirely off-screen.

Ornamental Hairpin (Hiroshi Shimizu, 1941)

That Kido should be branded a war criminal by postwar U.S. occupation forces for the fistful of military-themed movies he’d produced against his better judgment would never cease to gall him, especially as he suspected that the envy of rival studio bosses was secretly to blame. He nevertheless began capitulating anew. Following occupation directives, he ordered the maker of the flavorsomely titled battle-cry Songs of Allied Destruction (45) to spice up the following year’s Twenty Year Old Youth with Japan’s first big-screen kiss. In the Fifties Shochiku grew less and less pioneering in its productions, concentrating mainly on “women’s pictures” that moved increasingly away from the hard-hitting headlines of Mizoguchi’s Women of the Night (48), and toward the mildly satirical brassiness of Keisuke Kinoshita’s Carmen Comes Home (51), Japan’s first full-color feature. The home drama flourished, and an ever less conspicuously capricious Ozu continued his watch over Shochiku’s ever quieter house. One mark of Kido’s post-war resentment would nevertheless remain: where the Occupation forces had declared depictions of Mt. Fuji as “too feudal,” the minute MacArthur’s forces sailed off into the sunset, Kido ordered up the baby-blue skies and snow-capped vista of Fuji’s mountaintop that serves as Shochiku’s logo to this day.

With the Sixties approaching and the box office sliding, Kido—having missed the boat on the sensationalized taiyozoku (sun tribe) youth flicks that had recently earned healthy returns for Nikkatsu and Daiei—decided to break with company policy and promote a fledgling and fresh-idea-filled filmmaker not yet 30 years old. The risk seemed small enough, and the potential payoff in youth-market revenues large, but what seemed like foresight would soon prove exactly the sort of self-inflicted blindside that would contribute to Donald Richie’s characterization of Kido’s once-venerated and seemingly invincible dream factory as “the hapless Shochiku.”

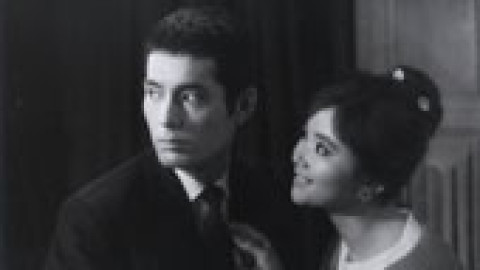

That filmmaker was Nagisa Oshima, whose “New Wave” 1960 trilogy—Cruel Story of Youth, The Sun’s Burial, and Night and Fog in Japan—proved so ideologically corrosive and politically incendiary that an infuriated Kido finally yanked the third installment from theaters after just three days. Oshima’s resignation from the studio quickly followed, as did his resolution to change the shape of Japanese film forever. Kido had developed cold feet over the films he’d financed in the past, even holding up the release of Ozu’s I Was Born, But… when the director worried that it had turned out “unexpectedly dark.” But, having buried the sun but a few months previously, Oshima fully intended that Night and Fog in Japan be more than simply dark; it would be a plummet into the eternal pitch. Deliberately dense with overlapping flashbacks and bilious recriminations, the film is a banshee’s wail about the follies of youth and the failures of revolutionary street politics, staged in Brechtian blackouts and shot in slitheringly theatricalized long takes. Scarcely the sort of youth flick Kido had hoped might click with audiences, Night and Fog was more akin to a high-art horror movie about a wedding ceremony for rabid werewolves, where the guests continually lunge at one another with salutatory toasts that climax in, “I’d like to tear you all to bits!”

Night and Fog in Japan (Nagisa Ōshima, 1960). Photo by Shochiku Kinema Kenkyu-Jo/Kobal/Shutterstock.

Critically speaking, Kido’s promotion of Oshima to director in 1959 proved far more disastrous than his years-earlier alternations between indifference and antipathy that resulted in the ouster or voluntary exiting of Shochiku auteurs including Shimizu, Mizoguchi, and Mikio Naruse, of whom the emotionally color-blind Kido once quipped, “We’ve already got an Ozu.” (Shohei Imamura and Seijun Suzuki both began as director’s assistants at Shochiku, though both left before making any films of their own.) Indeed, one can only begin to imagine the chagrin of the Ozu-loving executive when, having failed to cash in on both the taiyozoku craze and the giant monster jamboree that was keeping Toho afloat, he realized he’d inadvertently created a teenaged Frankenstein that was suddenly belching fire all over the home dramas that served as the studio’s aesthetic backyard. And yet here came Oshima—a towering, untamable behemoth born from the black-market bile of the American occupation! A defiant and gigantic boy glowering down at the grown-ups as he crashes into everything! Castle Shochiku’s home-grown Anti-Ozu!

Not that the old tofu vendor himself appeared, on the surface, particularly concerned. Perhaps Ozu had simply managed to internalize all those elliptical absences from his movies, and let whatever nuisances the noisome Oshima might have posed disappear into the Zen spacelessness of a synaptic splice. Still, the presence/absence issues that he’d long been tinkering with continued. A decade earlier, Ozu had worried that the climax of Late Spring (49), with Chisu Ryu silently peeling an apple as he sits alone in his house at the end of his daughter’s wedding day, smacked rather heavily of art-for-art’s-sake. Now he found himself working for a studio where, in movies like Cruel Story of Youth, the teenaged thug and apprentice pimp who passed for the movie’s hero wouldn’t just ruminatively regard that apple; he’d pornographically devour it while pouring sweat and pondering the supine body of his girlfriend, still under anesthesia from the abortion he’d ordered her to have an hour before.

That Ozu may have never even seen Oshima’s films is possible, though unlikely. The reverse is less likely still. A former film critic, Oshima knew exactly where he’d come from, and when he determined to sabotage his cinema’s history, he knew exactly how short to cut the fuse. Take another look at the moment in Cruel Story when that “heroic” pimp meets his permanently pouting girlfriend, whose innocence he’ll soon violate in a log-filled harbor not far from Shimizu’s old hooker-stroll. Rushing in to rescue her from the geezer who’s given her a ride and begun to get grabby, our pimp-hero beats the would-be masher down to the concrete, stands to straighten his jacket, and as he turns to ask if sweater-girl’s all right, does a sudden, stiletto-sharp 360-degree spin on his heels—exactly the sort of well-rehearsed show-offery that every boy and boy-hoodlum back on Planet Ozu used to do. Is that the scent of tofu burning? Ozu smelled it too. Returning from his mother’s funeral, he wrote in his diary: “Spring has arrived. Cherry blossoms are in full bloom. Here I am agonizing over An Autumn Afternoon. Like torn rags, the cherry blossoms display a forlorn expression—sake tastes as bitter as gall.”

Cruel Story of Youth (Nagisa Ōshima, 1960)

Oshima continued, after a time, to let the studio distribute the films he went on to make through independent means. In 2000, he returned to make one final film under the Shochiku insignia, the deeply subversive jidai-geki entitled Gohatto—a film in which a whisper is made to seem altogether more radical than a scream. Ozu—whose first film, now forever lost, was a jidai-geki called The Sword of Penitence—finally took his leave from Shochiku, and slipped the surly bonds of earth as well, in 1963. His tombstone is famously inscribed with the Japanese character that signifies nothingness; it is pronounced, with a whisper, “mu.” Kido (whose grandson, a former lawyer with degrees from Harvard and UCLA, now runs Shochiku) hung on until his retirement in 1977. Later that same year, Ozu’s one-time assistant director, Shohei Imamura—who’d once famously remarked that while he was but a farmer, Oshima was a samurai—returned to the studio with a new project. What might Imamura have been imagining when he titled it Vengeance is Mine?