The Cleaning Crew

Film has always been a collaborative medium. Yet throughout its 120-plus-year history, the contributions of editors, actors, production designers, and other below-the-line talent have all too often been lumped into “the director’s vision” by audiences and critics alike. Now the question of who “authors” the final look of a film is murkier than ever. Out of habit more than out of principle, the central role of the director or cinematographer remains overstated, even as powerful VFX software has become an integral part of filmmaking. It is applied to virtually every frame of not only big-budget Hollywood pictures, as any audience member knows, but also small, talky indies and auteur-driven art films. Even most documentaries now employ VFX artists to “clean up” archival footage and tweak reenactments.

To a greater and greater extent, filmmaking means using VFX, whether or not audiences are aware of it: in the words of Justin Paul Warren, Digital Imaging Technician on David Gordon Green’s Manglehorn and Joe, “99 percent of the VFX you saw [in any film] is the VFX you never knew you saw.” This invisible filmmaking is pervasive: “beauty work” on actors’ images (removing dark circles, pimples, scars, sweat, or other contractually erased objects of insecurity); landscape extensions (making buildings taller or adding trees); fixing mistakes made during shooting (erasing boom mics, wires, and C-stands that got into the frame); stitching together shots (a faked extended-take tracking shot, or four parts of a bravura panorama). These and other efforts serve to enhance, replace, or streamline work traditionally done by makeup artists, editors, art directors, and cinematographers.

Recognizing how routinely and fundamentally VFX is changing what cameras capture also means altering how we think about cinema. Even with the occasional viral news item—as when technicians had to erase Daniel Craig’s new pair of gloves from a fight scene in Skyfall—it can be difficult for viewers to appreciate the craft and skill involved, beyond the curiosity value of the making-of stories. Yet the scope of participation by VFX artists raises profound questions of authorship. Do VFX artists in fact have more influence over the mise en scène and overall visual look of a film than the director or cinematographer, or are they just craftspeople working toward a shared goal? As David Bordwell rightly acknowledges in his recent book The Rhapsodes, filmmaking is not simply a Fordian system whereby each department on a production contributes a standardized component to create the finished product. It’s a matter of artisans who leave their unique marks on what we’re watching.

History of the World, Part I

The art of digital VFX extends cinema’s older “art of the hand” traditions. Much of what visual effects handles today was formerly accomplished through production design and matte work. Traditional mattes were hand-painted onto glass or sheets of black cardboard and then combined with live-action footage. Individual artists had their own identifiable style that reflected and refracted the vision of the director: Albert Whitlock, an Academy Award–winning master matte painter, worked on everything from Alfred Hitchcock’s The Birds to David Lynch’s Dune to Mel Brooks’s History of the World, Part I. Just as with matte backgrounds, the work of VFX artists is intended to be seamlessly integrated into the rest of the film, and that applies to the filmmaking process as well: through the standard technique of 3-D tracking, a VFX artist places elements in a shot precisely on the path that the camera is following, using algorithms to ensure physical accuracy.

Just as with VFX, some of the most naturalistic matte work was kept quiet: an uncredited Warren Newcombe painted the sun-splashed highway for Lana Turner and John Garfield’s abortive attempt to run away together in The Postman Always Rings Twice. Making that scene succeed flawlessly required an exacting alignment of lighting and positioning of the finished matte, and the equivalent care is necessary today. The Coen Brothers’ Inside Llewyn Davis is not a film that looks especially reliant on VFX, but for the singer’s ill-fated drive to and from Chicago, the use of green screen meant that DP Bruno Delbonnel lit the physical set with a mind toward what the VFX would ultimately help create. Peter Doyle, who graded all of the Lord of the Rings movies and several of the Harry Potter films, came up with a special workflow for Inside Llewyn Davis whereby the film was scanned and then graded 80 percent of the way. This allowed the directors to make aesthetic judgments based on what the film would ultimately look like when finished, rather than suggesting alterations later on. The Coens’ tendency toward meticulous storyboarding eased the process behind realizing this sequence (making it more akin to working with celluloid), but part of that kind of analog planning now routinely allows for VFX.

What complicates our perception of VFX as an additive element rather than a motivating force is its pervasiveness at multiple stages of the filmmaking process. It can be integrated during preproduction or during shooting, though most frequently during both. Certain scenes may be written with the express intent of including VFX; others may have VFX added after the dailies are shown to the editor, director, and cinematographer. Furthermore, determining the final look of a shot or scene with VFX is collaborative across departments. For films that require set extensions, the lead input comes from the art department and production designer, providing historical reference points for which buildings would have existed at the time; for wholly imagined, computer-generated images, the process is an ongoing one between director, production designer, cinematographer, the producers, and VFX artists.

On the set of Inside Llewyn Davis, courtesy of Alexander Lemke

To cinematographer Bradford Young, that process is a welcome development. Young shot Denis Villeneuve’s new film, Arrival, part of a varied and outstanding résumé that ranges from Ava DuVernay’s Selma to Dee Rees’s Pariah to the forthcoming Star Wars Han Solo film. Rather than an imposition, VFX that enters later in the process can appeal more to Young than pre-planned VFX that places restrictions on shooting.

“When you’re in a scene dealing with fundamental human drama, the last thing you want to think about is the alien or a building that doesn’t exist that they’re going to add later,” Young explained. “Shots that weren’t intended to have visual effects elements, on a good day—and that’s pretty much most days—actually seem to be a little better because they’re not as planned. You don’t have the tension of being on set and somebody telling you that it can’t happen.” A director and an editor might decide to adjust a shot—“add” lighting, for example, which might seem an affront to a cinematographer. But it’s all in a day’s cinema: “Those shots end up being great, because you’ve given them the raw bones and you’re adding to that. Those shots, I find, have a better texture.”

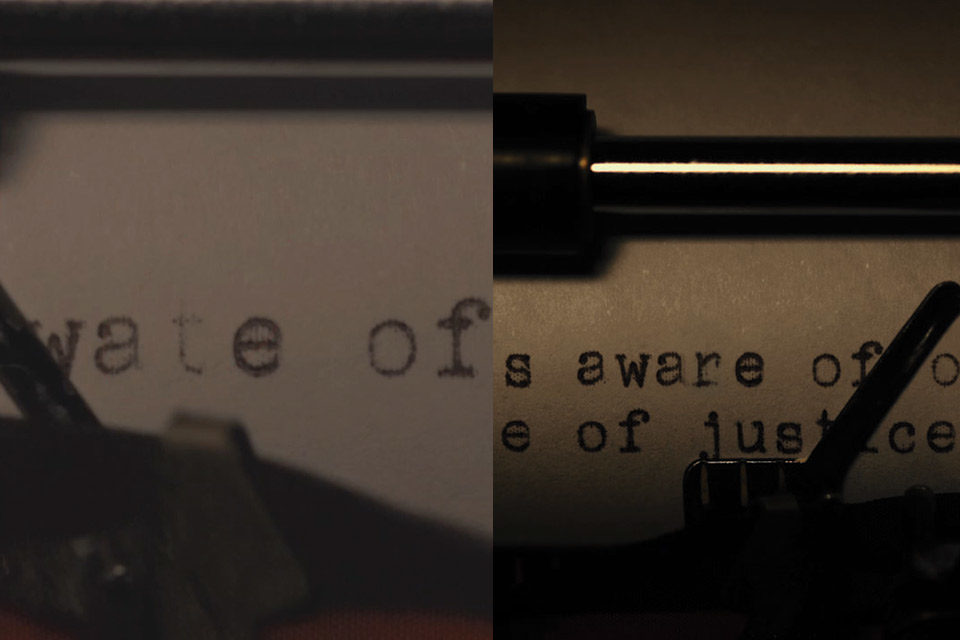

If the collaboration between the cinematographer and the VFX department is more nuanced and positive than might be expected, changes that fall under the category of beauty work are a far more delicate operation. Rather than ensuring that, say, a Manhattan street corner circa 1976 looks historically accurate, it involves manipulating actors’ faces. Although these kinds of effects are written more often into stars’ contracts than into scripts, they require a great deal of aesthetic consideration. Senior finishing artist Katie Hinsen, who has worked on films as diverse as District 9, Victor Charlie Romeo, and A Kind of Murder, works at a variety of New York postproduction houses, and describes an approach to beauty work that echoes the great Hollywood makeup artists while incorporating a sense of compassion. “As a woman, I think I come at it from a different perspective. If that were me 30 feet high, what would I want to be fixed?” Hinsen said. The ideology of the art form is not far from her mind, contrary to the stereotype of VFX as faceless technical wizardry. “It’s a sense of kindness, but I also want to be honest and truthful about what that person looks like. I think it’s really important to not perpetuate the real pervasive sense that Hollywood stars are inherently different from everyone else. I’m not going to make somebody look flawless.”

Before and after of A Kind of Murder

Beauty work has only recently been discussed at any length in public, in part because of the desire to maintain the sense of fantasy (Hinsen was not at liberty to discuss the exact changes she has made to the faces of famous performers). But these types of changes raise implications about what constitutes performance. Whereas Andy Serkis has argued that motion-capture CG animators don’t add anything significant to the performance and are “in effect . . . painting digital makeup onto actors’ performances,” in reality they are actively editing the performance while they create, and are, at the very least, selecting different aspects from the best takes. Just as motion-capture artists work on an artisanal level of tiny facial muscles and microexpressions, so does beauty-work VFX figure into performance in overlooked ways. Does the shadow cast by an “imperfect” nose give an emotional moment more gravitas and soul? Can a face that is “too perfect” undermine our ability to empathize (or simply distract us with its beauty)? Because the act of “reading” a facial expression is a complicated psychological process—and because we have no universal shorthand for describing what exactly actors do with their faces—it’s difficult to quantify what altering 1/24th of a second does to us on a visceral, emotional level.

As the allusion to contracts suggests, what that final performance looks like isn’t usually up to a VFX artist. The approval and tweaking of these effects and grading take place across multiple rounds, and across different vendors: a smaller post house will handle certain changes (such as beauty work or set extensions) and then send more complex CGI work off to another post house dedicated solely to VFX. Collaboration in the age of smartphones doesn’t have the same glamour as, say, the teamwork of artisans in the Freed Unit at MGM: QuickTime files are sent among members of the creative team, which can include the director, editor, cinematographer, art director, supervisors, and producers. For smaller-scale projects, the work can be done remotely, managed entirely through e-mail and Google Docs.

To ensure that footage is properly shot while mindful of what will be done to it later—and thereby reducing the amount of CG work to, say, accurately composite flowing water—productions will have a visual effects supervisor on-set. Victor Barroso, the VFX supervisor/coordinator at Worlds Away Productions who has worked in the industry since the 1980s, says that he attempts to think like the director when crafting an image, or when managing expectations: “You do have to have conversations with [directors], and pull answers from them sometimes: ‘What is it that you really want here?’” Instead of the disgruntlement of an anonymous technician, Barroso’s concerns suggest something closer to the work of a cinematographer interpreting the wishes of a director.

Arrival

Actual VFX work begins before or concurrent with the color correction process—another way in which the craft is intertwined with the most fundamental aspects of the camera image. Describing his work for Arrival, Young recalled, “We had a big question about photographic density when Amy Adams and Jeremy Renner first go into the spaceship. So we made sure that when we were looking over the characters’ backs out of the ship, that this stuff would be blown out. That required a big conversation between the visual effects department and me.” Colorists and VFX artists are usually not in direct contact with each other (unless it’s a smaller-budget production), but their work is inevitably connected. For instance, bringing up the brightness on a window can reveal a reflection that was previously undetectable, which will need to be erased digitally.

For several reasons, the art of VFX can easily fall prey to filmmaking-by-committee. That’s a charge that has been leveled at Hollywood for decades. But the approval process involving VFX can run awry rapidly, and grandly. As is true with faces and expressing emotion, just because something looks real doesn’t mean its changes aren’t perceptible on some deeper level. Instead of bursting into flames, an exploding car can be made to flip over multiple times, spew glass everywhere, and have the hood shoot off while engulfed in fire—the kind of overkill that would take longer to achieve with practical effects. This type of one-upmanship makes for great spectacle, but after a certain point it steps beyond the threshold of believability. This disconnect—we “know” that a car can’t explode like that, even though we’re seeing it happen—even if only felt in the back of our minds, has the ability to take us out of a scene in a way that models and clay never did.

If we can agree that VFX fixers working at all levels are at the very least, craftspeople, and at the very most, seasoned artists who can exert just as much control over the final image as cinematographers do, the question arises: how do we acknowledge their work? The level of discussion surrounding VFX—outside of specialty websites—seems to be on the level of calling cinematography “well shot.”

Life of Pi

It isn’t any easier on the filmmaking side. Joe Gunn, who works at FuseFX, a VFX post house, navigates more than just practical matters when shepherding a project. “There are a lot of people in the industry who don’t understand the whole process. There is the assumption out there, still, that the computer just does it, right? Not really. There’s still an artist there behind that computer working 12 hours a day to make your vision come true.”

The lack of understanding is reflected on a labor level: VFX artists, unlike every other department, are not unionized. This means that the price of their work is undercut by young and hungry people looking to break into the industry, or by overseas competition. (One of the most notorious examples of this financial strain is Rhythm & Hues Studios, the company that went bankrupt less than 10 days before winning an Academy Award for Life of Pi.) Studios bill non-domestic VFX work as “services”—which means that it’s not taxable—and pay much less for the same work that’s done stateside. This, in turn, leads many skilled artists in the U.S. to relocate to Canada or New Zealand; ever-tightening deadlines remain a plague.

It’s difficult to imagine any other below-the-line department being treated in an à la carte fashion that discourages apprenticeship. “Visual effects supervisors are filmmakers too,” Young said. “They’re artists. They know filmmaking as the craft of sculpting light and shadows.” Overlooking the work of VFX artists as superficial or as a glorified form of computer programming drops an entire swath of craftspeople from the discussion of film, not to mention cheating them of artistic recognition. Stick around for those extra-long credits: the VFX equivalents of Gregg Toland and Vilmos Zsigmond may be walking among us.