The Big Screen: Never Rarely Sometimes Always

A high school talent show opens Eliza Hittman’s third feature, Never Rarely Sometimes Always. Autumn (Sidney Flanigan) stands at a microphone, singing a cover of “He’s Got the Power,” accompanying herself on the guitar. Her energy is grim and the pop lyrics, about a man who makes her do things she doesn’t want to do, here sound alarming. It’s a stark contrast with the acts that preceded hers, which had a 1950s theme: girls in poodle skirts and boys with slicked hair, doing Bye Bye Birdie–type dance numbers or a doo-wop song. Solemn, contemporary Autumn cuts through the kitschy view of teenage life that’s straight out of Leave It to Beaver or the black-and-white sections of Pleasantville.

I kept thinking back to that sequence over the course of this often brutal film, in which Autumn, 17 and pregnant, journeys to New York City with her cousin Skylar (Talia Ryder) to seek an abortion. Hittman’s choice of opening comes to feel more and more pointed as the film unfolds. The bobbysoxer-milkshake version of teenage life wasn’t true in the 1950s, either—it was propaganda back then, too—but what powerful and damaging propaganda it was. There could not be a wider gap between its infantilizing vision and Autumn’s reality.

Autumn and Skylar come from a small, depressed town in Pennsylvania, a state where parents need to give consent for an abortion. There’s no question of Autumn asking hers, and the father of the child is never mentioned. The bus trip to New York is long, and once the two teens are thrust into Port Authority, lugging a huge suitcase, they’re bewildered by the city, trying to figure out mass transit and where they need to go. Unexpected things happen during this secret trip, decisions must be made, and the girls often have to improvise and problem-solve. They barely speak to one another, but they grew up together: language is not really necessary.

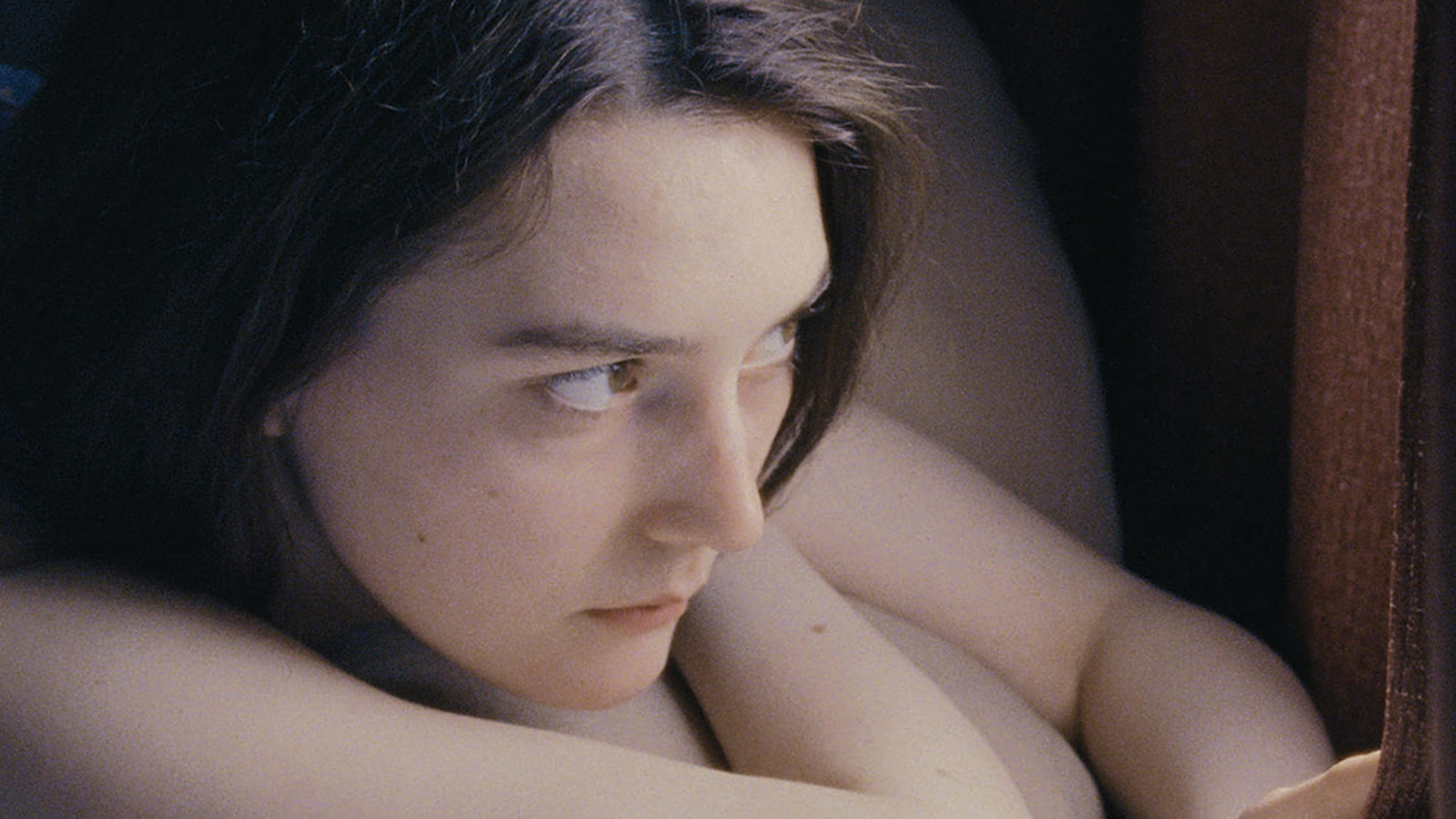

In Never Rarely Sometimes Always, the silences speak volumes. We must read the film through these muted passages, picking up what we can from gestures, glances, behavior. What the girls don’t react to is as important as what they do. There’s a moment late in the film where Autumn reaches out and links her pinky with Skylar’s, and it’s filled with poignancy and pain. Some things are beyond words. Cinematographer Hélène Louvart, who also shot Hittman’s 2017 film Beach Rats (as well as Happy as Lazzaro and last year’s Invisible Life), keeps the camera very close to Autumn’s face throughout the film: the real story is there, in what Autumn thinks, feels, experiences. Both Flanigan and Ryder give eerily naturalistic performances, understanding how the girls camouflage their insecurities.

There are some similarities between Never Rarely Sometimes Always and Cristian Mungiu’s searing 4 Months, 3 Weeks, and 2 Days, and a similar political urgency ignites both films. Abortion is still legal in this country, although it’s being encroached upon every day, and hostility toward women’s bodies comes from the highest office in the land. When Autumn goes to a women’s health clinic in her small Pennsylvania town, she is given a pregnancy test and then shown a graphic video about abortion.

Portraying Autumn’s journey, Flanigan is a serious, almost stoic, presence. Autumn is practiced at maintaining a deadpan demeanor, but underneath it is terror and loneliness, and far beneath that is a pain she can’t really allow herself to feel. But when she answers a series of questions asked by the counselor at Planned Parenthood (the title of the film comes from the four possible answers to each question), emotions boil to the surface, ambushing her. This is the first specific glimpse of what this young girl has been through in her short life. Flanigan’s tough demeanor has been hiding that all along. It’s overwhelming.

Hittman’s feeling for adolescence is extremely intuitive, and her approach—in It Felt Like Love (2013), in Beach Rats, and now in Never Rarely Sometimes Always—is not abstract, sentimental, or intellectual. She is not tempted by melodrama or polemic. Her interest is sensorial and experiential: it’s all about textures and faces, behaviors and silences, how destabilized everything is when you’re young and hormonal and inexperienced. The societal and cultural issues at play in Never Rarely Sometimes Always are only background noise. Navigating sex and “growing up” is a treacherous business on a good day, but even with the bombardment from television and magazines of well-meaning empowerment messages about consent and boundaries and peer pressure, not much has filtered down to the population for whom it would really make a difference—at least not in Hittman’s films. She does not look back on puberty with nostalgia; her films would be much different if she did. But her stance also isn’t that of a horrified protective adult. Because of this, she is frank in a way that other directors often aren’t. She’s in the thick of it with her teenage characters—she remembers so well what it was like to be them.

Sheila O’Malley is a regular film critic for Rogerebert.com and other outlets including The Criterion Collection. Her blog is The Sheila Variations.