Alex Cox’s 10,000 Ways to Die: The American Dreamer

In 1970, Universal gave Dennis Hopper the Citizen Kane deal: $850,000 cash to make a movie, complete with final cut. What had been a tremendous deal for Orson Welles was a lousy one for Hopper. Citizen Kane was made 25 years earlier on a studio back lot; Hopper’s project, The Last Movie, was an ambitious picture-within-a-picture, to be shot with an international cast in Latin America. The average budget of a Hollywood movie in 1971 was between three and 30 million dollars. His last picture, Easy Rider, had grossed $30 million for Columbia. As a bankable director he should have gotten at least three times as much money for his next picture; instead, if he went over budget, he would lose control of the edit and his financial interest in the film. He was being screwed.

Rumors about the debauchery and drug-taking that surrounded the shoot of The Last Movie are legion. Some of them are even true. But Hopper was an on-time, conscientious director and his indefatigable producer, Paul Lewis, kept the logistics together. The shoot finished on schedule and under budget. Then came the editing.

Hopper was one of those directors who loved actors and being on the set, and hated the cutting room. He took 48 hours of footage to his compound outside Taos, New Mexico, where a substantial entourage awaited him, and made a first cut of the film. He was visited by brother directors Nick Ray and Alejandro Jodorowsky, who suggested re-editing the picture. Hopper complied. Postproduction, scheduled for three months, expanded to more than a year. Universal executives would call Lewis and demand the finished picture immediately; Lewis would fly to New Mexico and tell Hopper; Hopper would get on the phone to the executives, who flattered him and promised him more time to edit; then they would be on the phone to Lewis again, demanding the finished film.

The American Dreamer

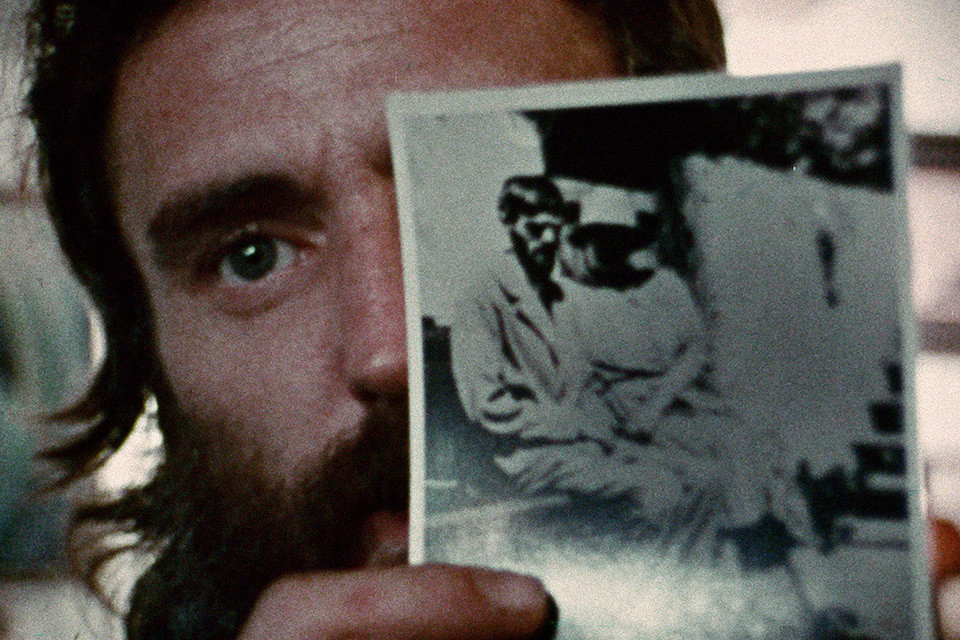

Into this morass stepped the late L.M. “Kit” Carson and Lawrence Schiller, proposing to Hopper that they make an “experimental documentary” about him, titled The American Dreamer. Today we would recognize this as a reality or lifestyle show, but at the time Carson and Schiller’s mix of to-camera interviews, cutting-room scenes, shots of lethargic partying, and an exquisitely embarrassing “be-in” involving Hopper and 30 free-thinking chicks was unique. There was nothing to compare it to. (The same can be said of its subject, and of the remarkable film he was struggling to complete.)

Yes, it was unwise of Hopper to let these guys into his home and act the (scape)goat (“I smoke marijuana! Society has made me a criminal…”), just as it was unwise of him to play political games with a powerful studio, unwise to attempt a project as original as The Last Movie at all. But in that lack of wisdom there was creative genius and a massive knack for self-promotion, and the origins of the Hopper brand…

The American Dreamer

After many years languishing on videotapes and old 16mm prints, The American Dreamer is being released in cinemas and on DVD and Blu-ray by Etiquette Pictures in a visually cleaner “complete version” based on scans of four different prints. The American Dreamer was distributed exclusively on college campuses and did good business there; these four last prints were found in campus film libraries. Only one print of The Last Movie remains, at the Academy Film Archives in Los Angeles. The film was killed by the studio, and—mysteriously, since the rights reverted to Hopper’s company—remains unviewable today.

Why no boxed set of The Last Movie? Why no streaming availability? No DCP re-release? The American Dreamer and my own documentary about the making of the film, Scene Missing, contain glimpses, but what of the film itself? The Last Movie is Hopper’s most complex work, received a major prize at the Venice Film Festival, and needs to be seen in its glorious, discontinuous entirety. Remember, critics! You can’t hate or diss a film you haven’t seen.