Worldly Pleasures

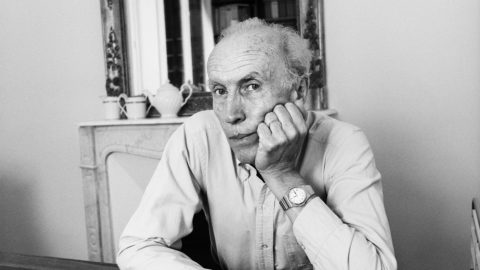

Sacha Guitry (1885-1957) has been likened loosely—very loosely indeed—to a French Noel Coward. As an auteur-Lothario, Guitry was married five times, each time to a screen siren, namely Charlotte Lyses, Yvonne Printemps, Geneviève de Séréville, Lana Marconi, and Jacqueline Delubac. By contrast, Sir Noel was one of the most notorious gay celebrities of his time. And Sir Noel was frequently honored at home and abroad for services to the Allied cause in World War II, not the least of which was the rousingly patriotic 1942 naval epic In Which We Serve. Guitry, on the other hand, was arrested briefly in 1944 for allegedly collaborating with the Nazis during the German occupation of Paris. He was jailed for 60 days awaiting a trial that never transpired, after the prosecutor had been reduced to placing ads in newspapers requesting witnesses to Guitry’s “crimes” to come forth and testify against him. No witnesses emerged, and Guitry was released.

But the damage to his psyche had been done, and Guitry spent the last years of his life in bitter disillusion with his fellow Parisians, whom he had entertained for so many years with over 100 plays that he had written and produced, and in which he had acted, and a host of movies drawn from this treasure trove of material. These dated back to his childhood years with his actor-father who had brought him from his birthplace in St. Petersburg to Paris, where Guitry père had carved out a niche for himself as a celebrated actor on the stage. There Sacha made his own acting debut in his teens and at 17 wrote his first play.

His early films came out in a pre-Bazinian era that worshipped the montage theories of Sergei Eisenstein to the point that Guitry’s early works on the screen were dismissed as too static and “theatrical.” Yet when his collected works were revived at the 1993 New York Film Festival, critics and audiences were entranced by Guitry’s brand of confessional cinema, which spotlights the often lyrical frankness of his own stage performances and those of his leading ladies. These included the illustrious Arletty in Désiré (37), only eight years before she became the mesmerizing female temptress of Marcel Carné and Jacques Prévert’s Children of Paradise.

Désiré

Of course, Guitry remained a child of the Parisian stage throughout his cinematic career, but his candor and unabashed sensuality have endured over the years, so as to provide an invaluable evocation of Gallic esprit on both stage and screen. The new Criterion DVD collection of four of Guitry’s best movies, two adapted from the stage and one from a novel, are (in order of original release) The Story of a Cheat (36), The Pearls of the Crown (37, co-directed with Christian-Jacque), Quadrille (38), and Désiré (38).

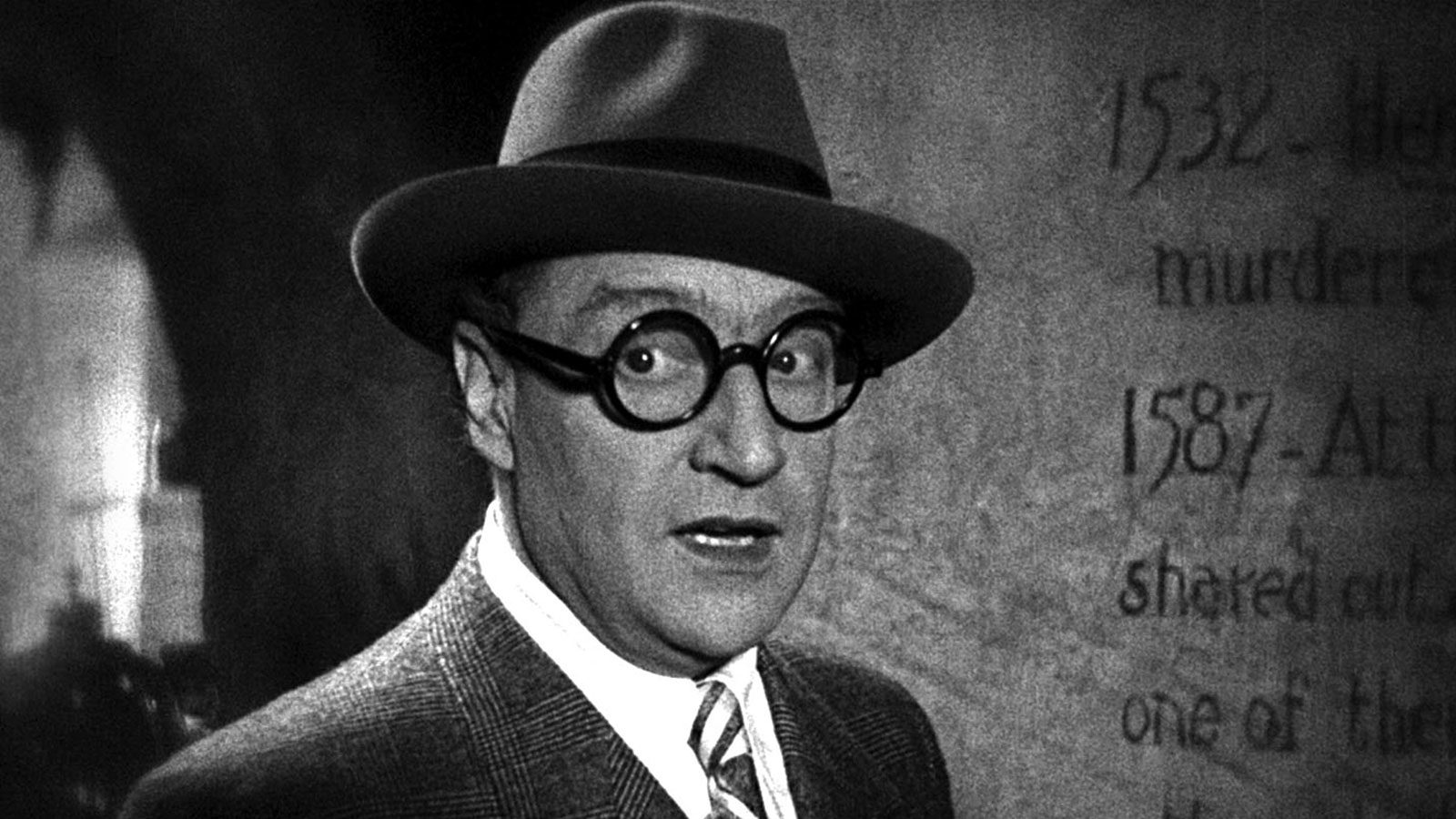

In each of these, Guitry projects his owlish charm and romanticism as an actor to dramatize the elaborate rituals of selection and rejection that mirrored the Parisian society of his intimates and his artistic collaborators over the years. The opening credits of The Story of a Cheat, for example, are an introduction to the film and a kind of manifesto: the gusto with which he introduces his assistants and craftsmen are but a prologue to glorious, cascading verbiage that turn his films into chamber concerts of arias, duets, quartets. Among those he worked with, perhaps the most important was Delubac, his third wife. In The New York Times, Dave Kehr provides an insightful appreciation of Guitry, entitled “The French Charmer You Don’t Know Yet,” arguing for her importance. As Kehr would have it, “The young Guitry had no use for silent film, if only because the medium was deaf to his rich baritone voice, an instrument he played with soaring virtuosity. He didn’t commit himself seriously to cinema until after he married the actress Jacqueline Delubac in 1935. Persuaded by his new wife that the movies would allow him to preserve stage productions that would otherwise be lost, he threw himself into filmmaking with his customary intensity.”

The Criterion set demonstrates once again that to be prolific is not to preclude being profound. One can only hope that this current sampling is only the beginning of a sustained revival of the works of Guitry as milestones of 20th-century French culture. The sparklingly sympathetic Delubac, hitherto unknown to me, is alone worth the price of admission. She and Guitry are most deliciously joined in the mathematical affinities of Quadrille in which they execute a completely choreographed exchange of partners such as one would never encounter in an American romantic comedy. By contrast, Désiré ends as the title character (Guitry), a valet with a history of dalliances with his mistresses, calls a halt to the proceedings after employer and servant have both begun talking in their sleep, unconsciously exposing a mutual desire and unsettling the upstairs-downstairs algorithm. Guitry ends up with neither the lady nor his fellow employee (Arletty), whereas the characters in Quadrille have found their soulmates and are just taking flight. This mixture of buoyancy and sadness within a cocoon of worldly compassion is characteristic of the universe of Sacha Guitry.