Patient Virtue

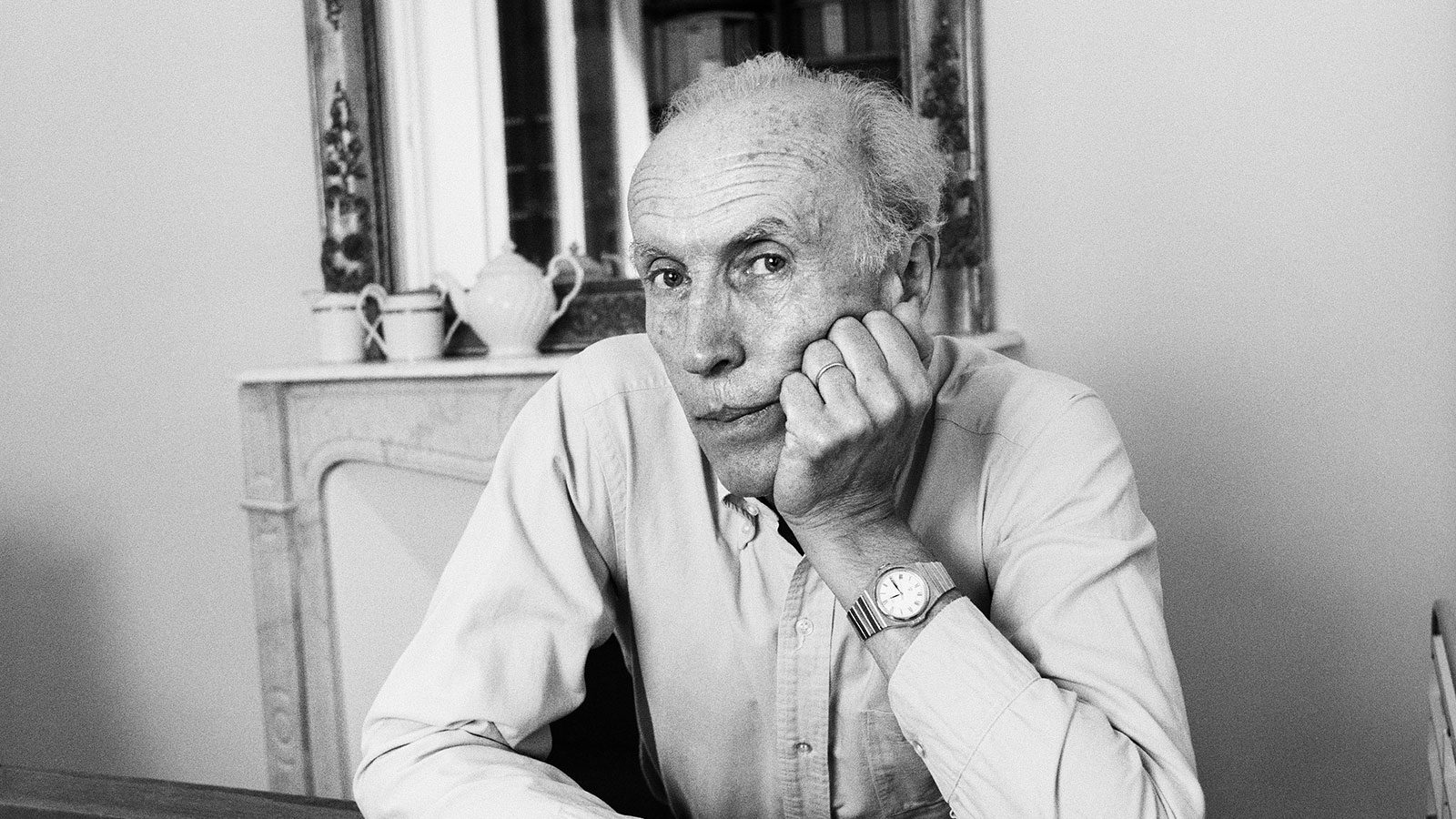

Eric Rohmer (1920-2010) made 50 films over a period of 57 years, beginning with the short Journal d’un scélérat (50) and ending with the 17th-century period piece The Romance of Astrea and Celadon (07). His recent death at 89 has already elicited perceptive testimonials to his cinematic achievements from Dave Kehr, André Aciman, and A.O. Scott in The New York Times. Both Kehr and Aciman recalled the philistinish dismissal of the illustrious writer-director-auteur by a hard-boiled detective played by Gene Hackman in Arthur Penn’s Night Moves. “I saw a Rohmer film once,” he reported. “It was kind of like watching paint dry.”

Curiously, in the original screenplay by Alan Sharp, the paint smear is applied to Claude Chabrol. I say “curiously” because the often violent world of Chabrol stands in stark contrast to the gently passionate cosmos of Rohmer. So why then the switch from Chabrol to Rohmer in the movie? Probably because Rohmer had become more prominent in American art-film circles than Chabrol, and thereby made a more laughable target, especially for his extreme “talkiness.” Another curious coincidence in the pairing of Rohmer and Chabrol is that they collaborated on the first serious book-length analysis of the films of Alfred Hitchcock, though neither could be said to have imitated Master Alfred. Chabrol always acknowledged a stylistic debt to Fritz Lang, whereas Rohmer blazed a new trail for the cinema to follow in the tradition of the 17th-century French philosophers Pascal, La Rochefoucauld, and La Bruyère.

The buzzwords for Rohmerian cinema—from the first of his films that I saw, My Night at Maud’s (69), to his last—were tact and restraint, thought before action, and discussion over impulse. These are certainly not the conventional or, let us say, “commercial” choices of most filmmakers. Still, Rohmer varied his narratives, casts, and locales sufficiently to avoid the curse of repetitiveness. He never established a stock company to parade his conceits. His stories were always fresh even when they were encased in serial categories.

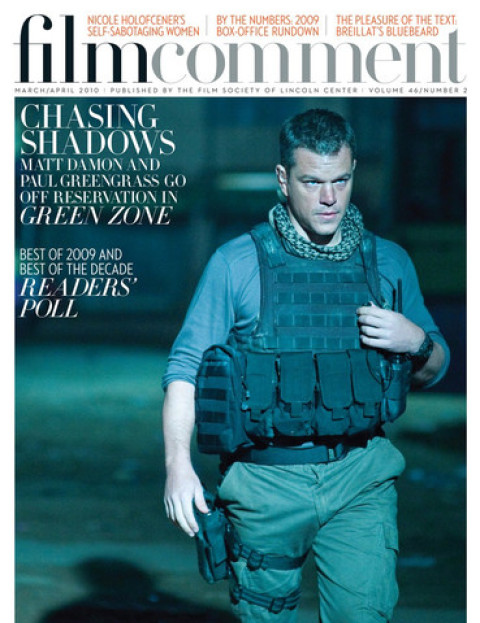

The Romance of Astrea and Celadon

Some Rohmerians preferred his early groupings to the later ones, but in all his films, his characters are endowed with seemingly endless curiosity about each other’s elective affinities and their own as well. Yet his works all end decisively with some new insight, for those of us forever under his spell, to savor.

Of course, Rohmer is not and never has been everyone’s cup of tea. That is why over the years I have developed a more defiant tone in his defense, as I did back on February 11, 2001, in The New York Observer in which I published a list of my favorite Rohmer films on the occasion of a 22-film retrospective:

- My Night at Maud’s

- A Tale of Springtime (90)

- Boyfriends and Girlfriends (87)

- Claire’s Knee (70)

- Pauline at the Beach (83)

- The Marquise of O (76)

- The Aviator’s Wife (81)

- A Tale of Winter (92)

- Autumn Tale (98)

- A Summer’s Tale (96)

“My list,” I wrote back then, “is Machiavellian only to this extent: My Night at Maud’s is the first film in the Film Forum series and Mr. Rohmer’s breakout film as well . . . The only film on the list I have not seen before is A Summer’s Tale, which I shall take this opportunity to watch, and I hope you will, too. I have never known Mr. Rohmer to let me down completely.”

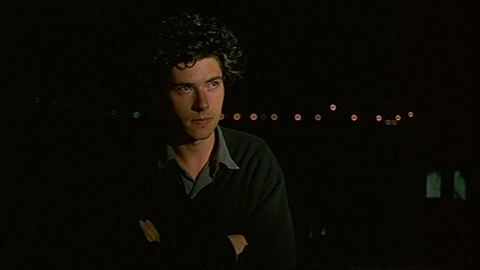

My Night at Maud's

Well, I did see it and he has still never let me down, and A Summer’s Tale remains on the list. I just hope that another Rohmer retrospective is in the offing so that I can revisit the settings in which the filmmaker has chosen to place some of the most charmingly articulate members of both sexes in the history of the cinema.

What are some of the great moments in Rohmer’s ever-yearning oeuvre? I suppose one occurs when Jean-Louis Trintignant’s piously repressed Catholic character in My Night at Maud’s discovers at a beach that his seemingly equally pious Catholic wife (Marie-Christine Barrault) has more to hide than he does about his abortively scandalous night spent with a divorced woman named Maud (Françoise Fabian). Then there is the cathartic climax of Boyfriends and Girlfriends, when the very vulnerable clerical worker (Emmanuelle Chaulet) sobs with relief after discovering that her boyfriend has not betrayed her with her friend.

In an apparent departure from his usual apolitical subjects, Rohmer’s next-to-last feature, Triple Agent (04), invades the treacherous arena of European espionage before World War II through the uneasy marriage of guileless Greek-born wife Arsinoé (Katerina Didaskalou) and Fyodor Voronin (Serge Renko), a former White Russian general in exile in Paris. During the years of Léon Blum’s Popular Front premiership, the ever devious Voronin serves in an intelligence capacity for a Czarist veterans’ relief organization. The period setting is augmented with astute insertions of newsreel footage of that era’s shifting loyalties and shameless betrayals. The focus remains on the ever insecure couple until their final downfall at the hands of enemies they can neither fully understand nor control. Along with Nikita Mikhalkov’s Burnt by the Sun, Triple Agent remains one of the most scathing indictments of the Stalinist regime in film history.