Ocean Tide

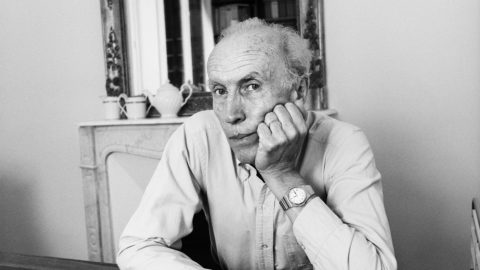

Claude Chabrol (1930-2010) was already in the process of being eclipsed by François Truffaut, Jean-Luc Godard, and Alain Resnais in the estimation of both critics and audiences in France when I arrived in Paris for the first time in 1961. Indeed, it was while I was dining on the Left Bank with Henri Langlois, the director of the French Cinémathèque, that I heard the first dissenting judgment about what I had assumed was a universally held opinion of the burgeoning French New Wave in the wake of the 1959 Cannes Film Festival. After patiently listening to my rapturous comments on Truffaut’s The 400 Blows, Godard’s Breathless, and Resnais’s Hiroshima mon amour, Langlois responded calmly but authoritatively with one name: “Chabrol.”

Hardly anyone agreed with him back then, and relatively few do now. Over the years, I myself wrote much more about Rohmer, Godard, and Truffaut than about Chabrol. But Langlois’s certitude stayed in my mind, and from that moment on, I paid closer attention and even came to the conclusion that Chabrol had actually been at the very crest of the French New Wave. As I wrote in my brief introduction to the late Mark Shivas’s enlightening 1963 interview with Chabrol: “Claude Chabrol quickly became one of the forgotten figures of the Nouvelle Vague even though he turned out eight very personal and professional features while his more esteemed colleagues were still floundering with fragments of films. Less iconoclastic than Godard and less lovable than Truffaut, Chabrol found himself so démodé by the mid-Sixties that he was forced to accept commissioned projects to keep his hand in.”

On the highest level it can be argued—and has been by many—that Chabrol’s films are too much about death and not enough about life. Yet what is more universal and omnipresent than death? His Les Bonnes Femmes (60) remains one of the great films of the Sixties and one of the precursors to the cinema of cruelty and compassion. The operative word in Chabrolian cinema is “feelings.” It is as true of the last shot of Les Bonnes Femmes as of late films like The Flower of Evil (03) and The Bridesmaid (04).

Although Chabrol and his Cahiers du cinéma colleague Eric Rohmer collaborated on the first perceptive study of the films of Alfred Hitchcock, Chabrol always considered his own style closer to Fritz Lang’s than Hitchcock’s. Yet ultimately his films were sui generis, specializing in an endlessly varying and genre-bending combination of black humor, sly mockery, melodrama, and bourgeois satire, all filtered through a sensibility that could both embrace and deride what he saw as the infinite supply of human folly. His films centering on women—especially those featuring (then wife) Stéphane Audran and later Isabelle Huppert—were uncanny in their understanding of women’s masochistic desires and hidden strengths, demonstrating an empathy that surpassed that of his supposedly female-oriented compatriots. Moreover his films are characterized by a humor wilder and less cerebral than that of his New Wave contemporaries. But as Chabrol himself observed, “There are no waves, there is only the ocean.”

I referred to that aphorism often, most recently in what turned out to be my final review of a Chabrol film, that of A Girl Cut in Two; in 2008. This reworking of the famous 1906 crime-of-passion slaying of the architect Stanford White by the husband of White’s mistress, the former Broadway chorus girl Evelyn Nesbit, struck me as fresh, very French, and up to date, with another provocative female protagonist. Ludivine Sagnier plays Gabrielle Deneige, a television weather girl caught between two men of neurotic dispositions and fluctuating attention spans. The denouement, as I wrote, “fulfills Chekhov’s dramaturgical imperative for The Three Sisters, which stipulates that if you show a gun in the first act, you’d better use it by the third. As for Gabrielle, she manages to survive both metaphorically being cut in two between Charles and Paul, and her actually seeming to be cut in two by a stage magician. This is one of Mr. Chabrol’s strangest films, but he still makes a ripple in his ocean.”

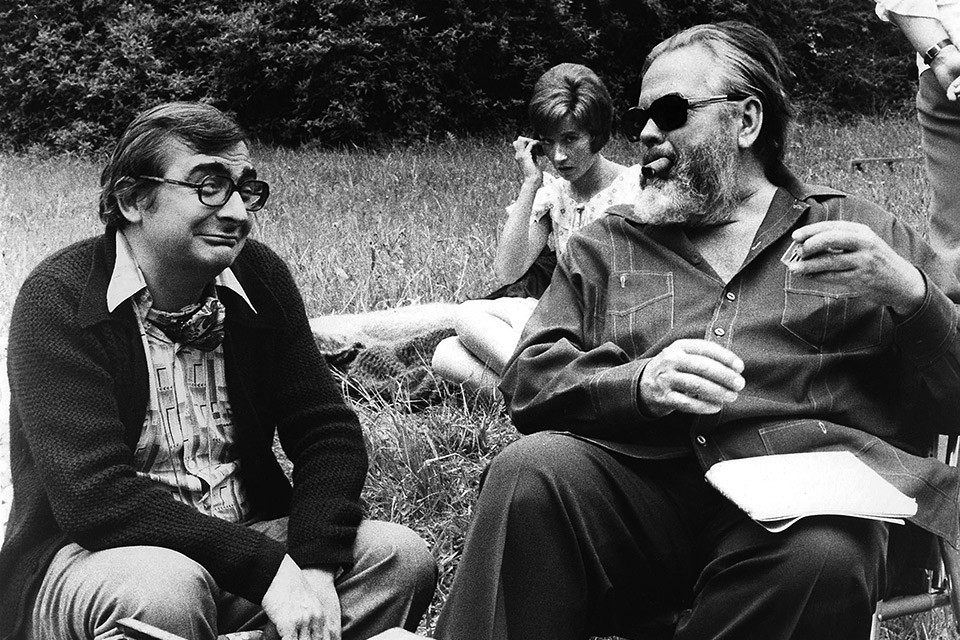

His final film, the slight but absorbing Inspector Bellamy (09), stars Gérard Depardieu as a detective who, in Chabrol-Hitchcockian fashion, discovers echoes of his own darker side in a suspected murderer. Ultimately, Chabrol’s half-century of filmmaking exemplifies a graceful blend of the comically grotesque and the emotionally sublime, worthy of Fritz Lang and Alfred Hitchcock alike.