Bakushi

(Ryuichi Hiroki, Japan)

A documentary about Japanese bondage masters and their models: artists of Eros at work, lustily creating pornography. While it’s wonderful to hear them describing, with candor and rare modesty, their passion, it’s something else again to watch the bondage sessions through Hiroki’s knowing, empathetic eyes: eroduction as high melodrama.—Olaf Möller

Beauty in Trouble

(Jan Hrebejk, Czech Republic)

A smart situation comedy that contrasts old and new Czecho-no-Slovakias. A woman must choose between her hapless, doltish mechanic husband and an older, wealthier émigré with a manse in Tuscany. The title comes from a Robert Graves poem and the soundtrack from Once’s busker-songwriter Glen Hansard. Think of it as Once told twice, this time from the girl’s POV.—Harlan Jacobson

Casting a Glance

(James Benning, U.S.)

A masterpiece by America’s greatest living builder of cinematic landscapes pays tribute to Spiral Jetty, a giant earthwork realized by artist Robert Smithson in 1970 on the Great Salt Lake in Utah. Benning visited it repeatedly over four years and filmed its radically shifting appearance and ambience. Creating a timeline via intertitles (from 1970 to 2007), Benning constructs something like a historical fiction. The soundtrack offers further “narratives,” derived from on-site recordings as well as from sounds that could or should have been heard, such as Gram Parsons and Emmylou Harris’s “Love Hurts” emanating from an unseen car radio.—Alexander Horwath

Fengming: A Chinese Memoir

(Wang Bing, China)

Wang follows his colossal nine-hour documentary debut, West of the Tracks (03), with a 184-minute account of the remarkable life of journalist He Fengming, from her repeated persecution during Fifties anti-reactionary campaigns and then the Cultural Revolution, through her rehabilitation in 1974. In one of 2007’s great screen performances, He talks for three hours while Wang calmly films, employing neither commentary nor camera movement.—Shigehiko Hasumi

The Forest of Mogari

(Naomi Kawase, Japan/France)

A beautiful, humane portrait of an ill-matched couple, each half confronting the pain of a loved one’s death. A withdrawn young nursing assistant in a home for the elderly befriends an unpredictable male resident. A car accident strands them in a forest where, in the film’s final third, through an understated tour de force of direction and camerawork, Kawase engineers catharsis for the characters and an epiphany for the viewer.—Chris Darke

The Kiss (Seppun)

(Kunitoshi Manda, Japan)

A story of amour fou in which an ordi-nary young woman living in Tokyo finds herself drawn to a man who has slaughtered a family for no reason and eventually falls in love with both him and his lawyer. The ending is astonishing and all three actors are excellent, in particular Eiko Koike, who plays the young woman.—Shigehiko Hasumi

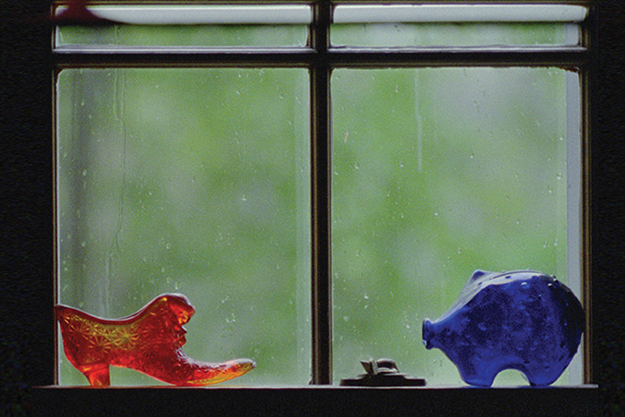

A Pitcher of Colored Light

(Robert Beavers, U.S.)

Portraiture, an American avant-garde staple since the Sixties, is a genre uniquely able to accommodate a multitude of stylistic approaches. Beavers, a contemporary master of formally brilliant, slightly chilly meditations on the conjunction of place and cinematic ontology, shapes this moving 23-minute portrait of his aging mother as a seasonal shift from oblique, static, autumnal views to a vibrant spring of animation and corporeal intimacy.—Paul Arthur

The Pool

(Chris Smith, U.S.)

Shot in India with amateur actors and one charismatic Bollywood superstar (Nana Patekar in the role of the father), The Pool tells the story of a hotel housekeeper who becomes obsessed with a luxuriant villa, its grounds, and the somber father and daughter who live there. Smith channels the neorealist tradition and the films of Ritwik Ghatak to arrive at a spare and deeply moving account of class and soul relations. Why has this wondrous and decidedly “undifficult” film found almost no takers?—Alexander Horwath

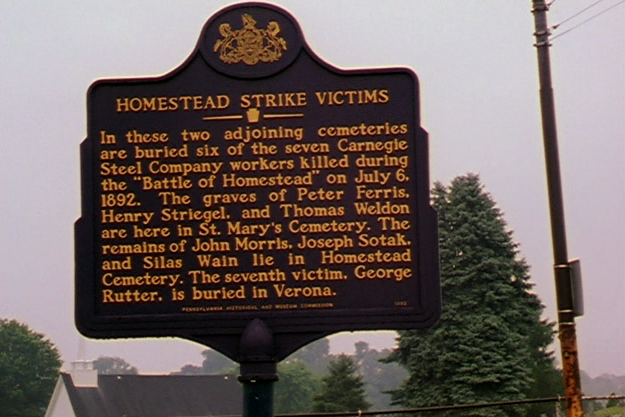

Profit Motive and the Whispering Wind

(John Gianvito, U.S.)

A Howard Zinn–inspired history of America—its thinkers, martyrs, rebels, and revolutionaries and their moments of glory and defeat, told through tombstones and historical markers, punctuated by trees and blades of grass ruffled by the wind. Think Straub-Huillet on the wings of Pudovkin going Newsreel.—Olaf Möller

RR

(James Benning, U.S.)

a majestic film of moving trains and how they “define the Z axis” in pictorial space, RR is among Benning’s finest works. Never in a hurry, it’s nevertheless a rush, a swelling of velocities in space and of the cultural and political meanings that attach themselves to the 43 trains on view. RR also gives us, to quote photographer Allan Sekula, “the image of a vibrating continuous pipeline of goods, a monstrous snake moving through the landscape, unstoppable until it meets a magical forest of windmills.” At 65, Benning is at his peak.—Alexander Horwath

Sad Vacation

(Shinji Aoyama, Japan)

Synthesizing two previous works, Aoyama brings together Kenji (Tadanobu Asano) from his 1997 film Helpless and Kozue (Aoi Miyazaki) from 2001’s Eureka. But you don’t have to have seen the earlier films to appreciate this one. A chance encounter leads Kenji to a new job at a transport company, and a reunion with the mother who abandoned him as a child and is now his boss’s wife. Suggesting that motherhood is more powerful than paternity, Aoyama starts a new chapter in his ongoing critical analysis of power relations in modern Japan.—Shigehiko Hasumi

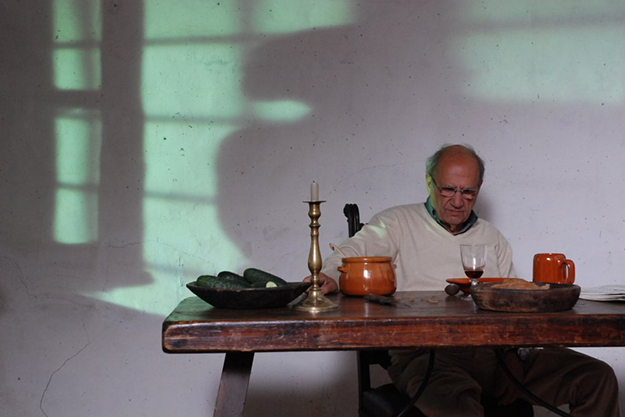

The Secret of the Grain

(Abdel Kechiche, France)

The director of Games of Love and Chance returns with a film rooted in a France far removed from the one usually seen on screen. This story of a fired shipyard worker who opens a restaurant discloses itself through concentric circles, revealing the many lights shining on the old man’s universe: his ex-wife and her children, his new companion. Moving constantly between the collective and the particular, The Secret creates its own complete world in which the trivial and the epic, the comic and the melodramatic ceaselessly trade qualities.—Elisabeth Lequeret

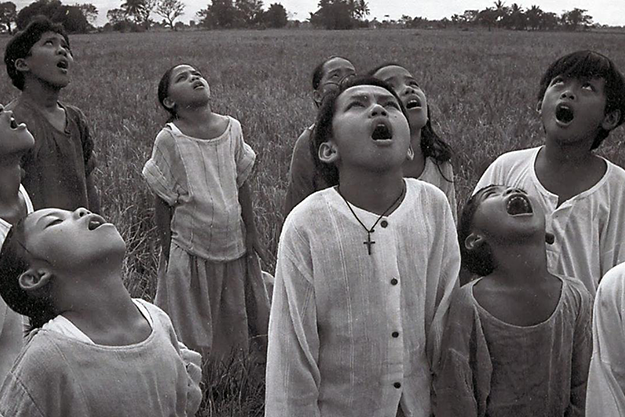

A Short Film About the Indio Nacional (or The Prolonged Sorrow of Filipinos)

(Raya Martin, The Philippines)

Through allegorical images this young Filipino filmmaker approaches an imaginary reconstruction of his people’s turbulent past, reinventing cinema’s expressive potential in the process. Historical reference points situate the action during the 1896 uprising against the Spanish occupation, providing the film with what appears to be its only certainty. The images seem suspended in time, self-reflexive, and with an overwhelmingly beautiful plasticity. They recall by turns the aesthetic and narrative origins of the Lumières and Griffith and the avant-garde principles of Warhol, ultimately tied together in a fable referencing Filipino mythology.—Manuel Yáñez Murillo

A Short Film for Laos

(Allan Sekula, U.S.)

A delicate 40-minute tapestry of impressions and observations from a trip to Laos: the Plain of Jars; the ancient capital during a festival; a knife forge; a small brick factory; pebble sifting. Call it an essay on what the world’s made of, i.e., iron and water and fire and earth. Wryly ironic, compassionate, and unprepossessingly simple.—Olaf Möller

The Silence Before Bach

(Pere Portabella, Spain)

The return of Portabella, after a 17-year hiatus, was one of the year’s major film events. The Catalan master hasn’t lost his cutting-edge instincts or his command of the enigmatic meter that underlies his work. His depiction of musical performance is materialist to the point of abstraction, his writing like calligraphy, his treatment of space architectonic, and his narrative free-floating. Transcending its subject, Johann Sebastian Bach, this film positions itself as an essayistic meditation on art as a destructive vehicle of social prejudice and an incarnation of the contradictions of European history.—Manuel Yáñez Murillo

The Trap

(Adam Curtis, U.K.)

No less ambitious and hotly topical than his seminal The Power of Nightmares (05), the latest from British TV’s foremost essayist is a three-part BBC series subtitled “What Happened to our Dream of Freedom?” Ranging across politics, philosophy, and economic theory, his thesis is that “freedom” today is conceived according to the narrow limitations of market calculations and an ideological perspective that views human beings as intrinsically selfish and isolated.—Chris Darke

United Red Army

(Koji Wakamatsu, Japan)

A three-hour portrait of an all-out class-war-driven faction of Japan’s ultra-left: the United Red Army’s emergence from the political struggles of the Sixties, its innumerable political causes, and its long, terrible disintegration in the winter of 1971–2 when 14 members died during brutal terrorist actions, climaxing in a 10-day standoff with the police. Both understanding and critical, this radically detailed, unflinching docudrama epic also has a poetic aspect. A monument.—Olaf Möller

The Unpolished

(Pia Marais, Germany)

In her slow-burning and moving chamber piece, Marais stays close to her 14-year-old heroine, whose longing for the straight life puts her at odds with her addict mother and ex-con father. The terrific cast and fine ensemble acting supply vital emotional authenticity. The Unpolished also features one of the hallmarks of the German New Wave: an ability to make the featureless nowheres of suburbia glow with heightened atmospheric intensity. Marais is a talent to watch.—Chris Darke