Festivals: Sundance 2003

Same as it ever was but more so’ is a fair description of the Sundance Film Festival in 2003: more movies (thanks to the new World Cinema Documentary section), more subscribers, more stars and starstruck gawkers, more patrons, more parties, more corporate sponsors and hangers-on, more swag, more press, more pr companies, more traffic, more drunken frat boys clogging up the highways and by-ways. Maybe there were fewer studio suits and agents, or maybe they were sulking in their two-thousand-bucks-a-night condos, given that John Sloss, the genuinely indie lawyer/rep/producer/financier, was already in control of most of the noteworthy and/or potentially marketable films. The only element showing a marked decrease was the snow—almost nonexistent for the entire ten days.

The schizophrenia that has characterized the festival in the post-sex, lies, and videotape era was blatantly symbolized in the two events that shut down half of Park City’s Main Street (Sundance’s version of Cannes’s Croisette). In order of appearance, they were Ben Affleck and J.Lo doing some impulse shopping, followed a few days later by an antiwar demonstration organized by Scott Beiben of the Lost Film Festival. While antiwar sentiment ran high among both festival participants and Park City locals (some of the biggest cheers during the closing night award ceremony were for Maggie Gyllenhaal, Tilda Swinton, and Darren Aronofsky, who used the opportunity to get the antiwar message beyond Park City to viewers watching the festivities on Sundance Channel), apparently no one considered the possibility of closing down the festival in protest (à la Cannes in 1968) or accepting his or her award in the name of peace.

The immediate news from Park City is that among the nearly 125 feature-length films, at least a dozen were notable. As a group, the documentaries were more satisfying than the fiction films, but the dramatic competition showcased two inspired formal hybrids: Shari Springer Berman and Robert Pulcini’s American Splendor and Todd Graff’s Camp. The former, a biopic of the underground comic book writer Harvey Pekar, won the Grand Jury Prize and was a favorite of critics and audiences alike. The latter, a musical set in a summer camp for teenagers who are so freaking retro they want to be Broadway stars, was passed over by the jury, largely ignored by the press, but embraced by audiences. (Sundance veterans know better than to trust any of what happens in Park City as an indicator of how a film will fare in a less hysterically acquisitive atmosphere.)

American Splendor

Let’s hear it for Cleveland as a breeding ground for tenderly subversive American art. Remember the visual epiphany in the middle of Jim Jarmusch’s Stranger Than Paradise, when John Lurie and Richard Edson visit Eszter Balint in the city sometimes known as “the-mistake-by-the-lake”? The trio goes sightseeing to Lake Erie, but it’s night, the snow is coming down heavily, and all they see is an undifferentiated field of gray—no water, no sky, no horizon—the emblem of the film’s hip minimalism and bleak humor. Harvey Pekar also hails from Cleveland, where he worked as a file clerk in a va hospital while writing American Splendor, the comic book series that detailed his daily life. Pekar’s work is more homey than hip, garrulous rather than laconic: Jarmusch empties; Pekar clutters. But for both, splendor is found in the margins. It’s this post-Beat mix of depression and wonderment that Berman and Pulcini, who are less than half Pekar’s age, capture in their adaptation.

Pekar and his wife, Joyce Brabner, are played by Paul Giamatti and Hope Davis (they deserved the special acting award that went to ubiquitous Patricia Clarkson). Sometimes, however, they’re replaced by the real Harvey and Joyce, sometimes the actors and the real people hang out on screen together, and the scratchy narrating voice belongs to Pekar alone. Pekar became fascinated with the comic book medium in the mid-Seventies through his friendship with R. Crumb. Because he couldn’t draw, he wrote the captions, dialogue balloons, and outlined the visuals, farming out the drawing to Crumb and various other comic book artists. Thus, there were as many Harvey Pekars as there were artists who depicted him.

Berman and Pulcini, whose previous film was the affable, conventional Off the Menu: The Last Days of Chasen’s, negotiate the intricate shifts in register and emotional tone without a misstep. What begins as quirky comedy takes a dark turn in the film’s last act, which is based on Our Cancer Year, the novel-length comic that Pekar and Brabner co-wrote about Harvey’s battle with lymphoma. At the risk of giving something away, I’ll just say that American Splendor has an amazing ending that finds transcendence in imperfection. What makes the film special throughout is the way its form mirrors its subject matter. On every level, it’s a film about unlikely marriages: of documentary and fiction, comedy and pathos, live-action and animation, and, of course, of Harvey Pekar and Joyce Brabner. And there isn’t a forced moment in any of them.

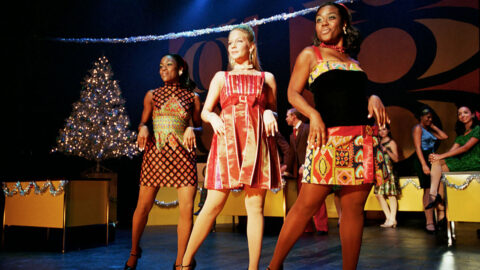

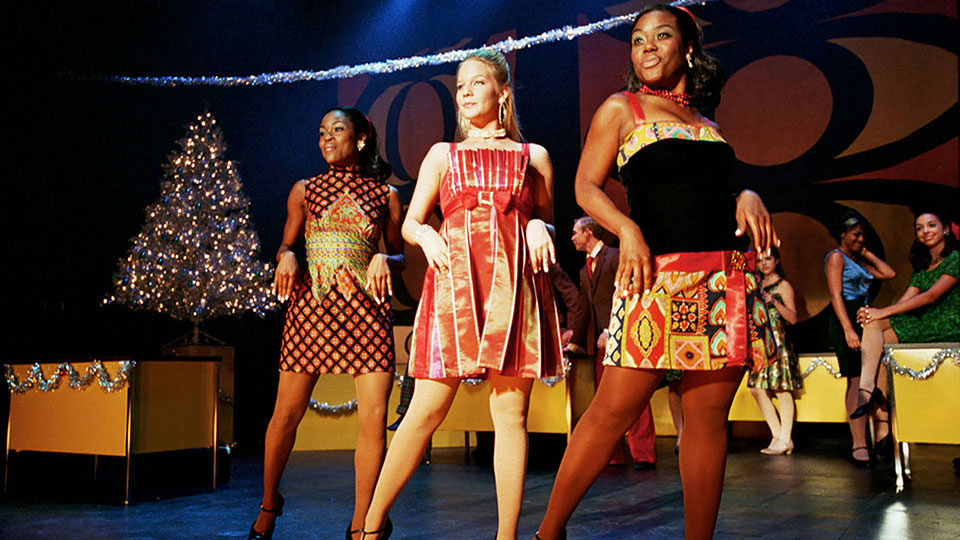

Camp

No less original and sophisticated in concept, but looser and less polished in execution (which is to say its form is exuberantly matched to its subject), Camp is based on its writer/director’s experiences at a summer boot camp for aspiring show-biz kids. Graff honors the talent of his young performers by keeping the musical numbers visually intact, i.e., without the frantic editing that made Chicago so enervating. The plot revolves around an off-kilter romantic triangle: plain but steadfast Ellen and wisecracking but vulnerable Michael are best friends who both fall madly in love with new boy Vlad, whose need to be loved supersedes minor issues of sexual orientation. Vlad’s narcissism is what makes him a potential star, but it’s also as agonizing to him as unrequited love is to Ellen and Michael. Graff reinvents the soapy, tastefully mature musical theater of the Stephen Sondheim era by infusing its songs with the longings and fantasies of adolescence. He cherishes the form (even the way the dialogue sounds in those long exposition scenes that bridge the eruptions of song and dance) the way Todd Haynes cherishes the tropes of the woman’s picture. Camp is all about the cathartic joy of performing. Fearlessly wearing its heart on its sleeve, it’s the anti-Fame, and I think it has legs.

Of the other competition buzz films leaving Sundance with distribution deals that guarantee their release: Peter Hedges’s Pieces of April is a silly sitcom with a Guess Who’s Coming to Dinner twist; Tom McCarthy’s The Station Agent is little more than a three-character, metaphorically burdened off-Broadway play, but Peter Dinklage’s understated performance gives it a bit of substance; Catherine Hardwicke’s thirteen captures the hysteria of teenage girls, and its depiction of how a good girl can go bad overnight will give parents nightmares, but the script, co-written by Hardwicke and Nikki Reed (who also plays one of the two teen leads), is as overexcited as the girls themselves, and its affirmative ending is unearned.

Showing out of competition, Masked and Anonymous (aka the Dylan movie), directed by Larry Charles and pseudonymously written by Charles and Bob Dylan, is set in the near future when the U.S. resembles a crumbling Banana Republic—a concept given a certain credibility by the current administration’s loot ‘n’ pollute policies. During the post-screening discussion, Charles mentioned that he wanted the movie to be like “Cassavetes doing Shakespeare,” which explains, at least, why Jessica Lange impersonates Gena Rowlands throughout. Dylan does about a dozen songs with his tight juke-joint band, and it’s worth sitting through the rest of the nonsense for both the music and for Jeff Bridges, in Fisher King mode as Dylan’s nemesis (a journalist, what else?).

Masked and Anonymous

A highlight of the World section, Gurinder Chadha’s Bend It Like Beckham sees the talented British director returning to the mode of her ebullient feminist adventure, Bhaji on the Beach. At the risk of providing ad copy for Fox Searchlight, the film, which concerns a teenage girl’s passion to play soccer, much to the dismay of her middle-class Indian family, plays like a combo of Love and Basketball and a much better My Big Fat Greek Wedding. The Beckham of the title is Britain’s reigning soccer superstar (if you didn’t know that, you might overlook the movie), who makes a mere 20-second guest appearance. No matter, Jonathan Rhys-Meyers is the only heartthrob needed.

A late entry that might have jazzed up the competition, Alex Steyermark’s Prey for Rock & Roll has Gina Gershon as a punk rocker turning 40 and wondering if it’s time to bow out. Gershon is game, but she can’t rock. As her fellow band members, however, Drea de Matteo is a goddess of cool and Lori Petty breaks your heart. Steven Trask’s music is as much a plus here as it is in Camp and The Station Agent. The best score, however, was Brian Eno’s almost subliminal one for Nicolas Winding Refn’s paranoid psychodrama Fear X.

Beyond the films themselves, the 2003 Sundance was notable for its continuing efforts to build an infrastructure for the production and exhibition of documentary film. House of Docs (sharing Main Street digs with the Filmmakers Lodge, where traffickers in fiction were welcome as well) was the hub of a festival within the festival, a place where American filmmakers could meet their counterparts from around the world and participate in panel discussions and presentations. There was Kim Longinotto from Britain, director of the impressively measured The Day I’ll Never Forget, which looks at the conflict over female genital mutilation within a Somali community in Kenya, sharing the microphone with Fouzia, the fragile, amazingly self-possessed pre-teen girl whose poem gave the film its title. Longinotto shows how the traditional culture is making its last stand around the control of women’s bodies and how women are as likely to be enforcers of the old order as men.

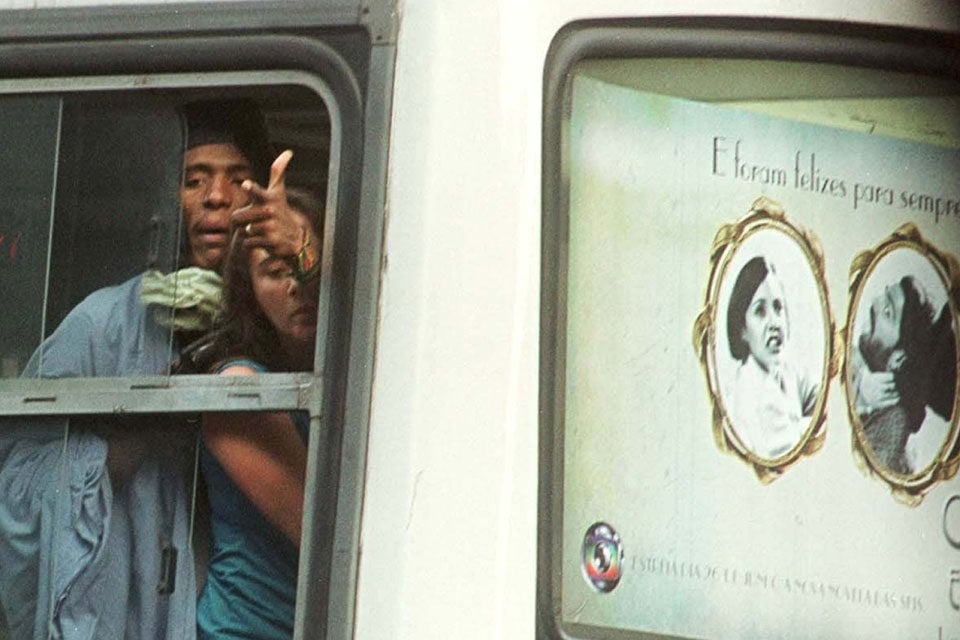

Bus 174

There were also Brazilian director José Padilha and coproducer Marcos Prado of Bus 174, which uses real-time network footage of a São Paulo bus hijacking in 2000 that had the entire country glued to their TVs for hours. The film intercuts the television coverage (the cameras were so close that you can see what’s happening inside the bus as if you were only a few feet from the windows) with interviews with surviving hostages and with relatives and social workers who had known the hijacker, himself a survivor of the infamous massacre of street kids by the police a few years before. Building an indictment of the media, the police, and the provincial governor for placing self-interest above saving lives, Bus 174 opens out from the people directly involved in the incident to an examination of institutionalized poverty and a prison system so dehumanizing that the hijacker would rather die than be returned to it.

After its first screening, Andrew Jarecki’s Capturing the Friedmans, the Documentary Grand Prize winner, became as hot a ticket as any fiction film, the result of its sensational subject (a middle-class, Long Island, Jewish family is destroyed when the father and one of the sons are arrested, tried, and imprisoned for multiple counts of child sexual molestation). There’s no doubt that the film delivers the emotional equivalent of a kidney punch, but that’s as much a result of the filmmaker’s attitude—better suited to entomological research—and the tidy Rashomon structure he imposes on material as it is to the Friedmans themselves.

By comparison, Jennifer Dworkin’s Love and Diane—an intimate, unruly portrait of a mother/daughter relationship and of three generations of a black Brooklyn family struggling with drug addiction; HIV; poverty; a byzantine, contradictory, often inane welfare system; and the self-destructive impulses that result from anger, shame, and abandonment—seems even more admirable and involving than it did in its New York Film Festival screening last year. Dworkin videotaped Diane and her painfully alienated daughter, Love, for many years, and the trust that developed between the family and the filmmaker allows us unusual access to their everyday life. Dworkin doesn’t sentimentalize her subjects and therefore leaves us ample room to feel annoyed and angry with their behavior as well as with the system that repeatedly betrays them. But in the end, it’s Dworkin’s empathy that allows one to understand Diane and Love’s experience and to care about what happens to them, or at least to ask if perhaps passivity in the face of social and economic injustice makes us more like Love than we would like to think.