Going Pro

The eternal moviegoing dialectic between the thrill of discovery and the slump of disappointed expectation becomes supercharged in the acceleration and compression of a film festival, any film festival. At Sundance, as ever, the action oscillates between more or less unheralded Competition contenders during the day and the more anticipated nighttime Premieres with their brand-name directors and casts. But where the world’s other major festivals offer the compensations of a seductive, or at least convenient, milieu, Park City in midwinter offers only spartan bootcamp hardship—it is the one essential festival for the committedly masochistic cineaste. The air is literally thinner up there, and the pickings are slimmer. Someday, the bottom may fall out of the indie market—and that’s when things will get interesting again.

Actually, this was the year the Dramatic Competition Jury (including Kevin Smith, Janet Maslin, and Tarantino producer Lawrence Bender) got it right. Karyn Kusama’s Girlfight and Kenneth Lonergan’s You Can Count on Me, which shared the Dramatic Grand Jury Prize, were the unmistakable standout films. Though more diverse and ambitious in style and largely less generic in terms of material, few of the Competition films came within hailing distance.

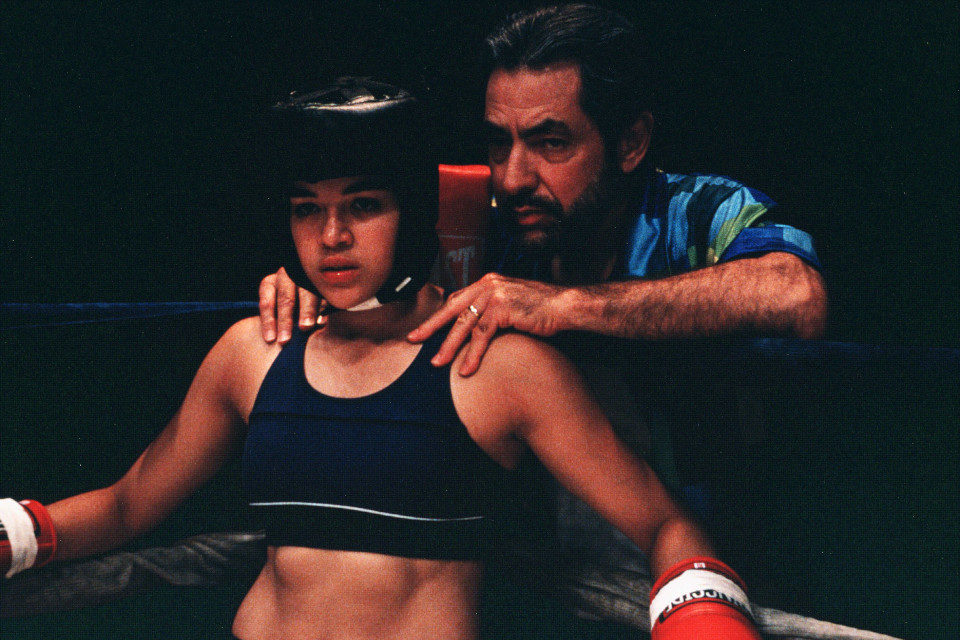

Grounded in a precise, unemphatic naturalism, Girlfight is the story of a strong-willed Hispanic teenage girl from Brooklyn who takes up boxing without her father’s knowledge, gradually wins her skeptical trainer’s respect, falls for another boxer, and eventually takes her first steps towards going pro. Although this material is familiar enough in outline, and succumbs to some slightly schematic emotional complications, there’s much that’s impressive: Michelle Rodriguez’s fiercely self-possessed, emotionally nuanced lead performance, an unostentatious, completely authoritative sense of the boxing and working-class milieu, excellent cinematography and production design, and fully imagined and well-acted secondary characters such as Jaime Tirelli’s trainer and Santiago Douglas’s boyfriend. There’s nothing hyped-up or rhetorical in writer-director Kusama’s handling of things, and no overt agenda or posturing—any sense of the protagonist’s struggle for self-esteem or to transcend her limited prospects emerges incidentally rather than didactically. Executive-produced by John Sayles, who appears in a cameo, this is the kind of authentic indie miracle that is Sundance’s raison-d’être. Kusama, who also deservedly won the best directing prize, is the festival’s most exciting find.

Likewise breathing fresh life into familiar material, You Can Count on Me comes on like a feel-good, sentimental, TV-movie tasteful drama about the virtues of smalltown life. Unusually sharp editing is the first hint that in fact it’s a superior, acutely observed comedy-drama about family ties and the struggle to find a sense of purpose, even managing to work in some genuinely metaphysical intimations. It’s buoyed by four immensely enjoyable performances: Laura Linney as a capable, responsible single mother; Matthew Broderick as her unsympathetic, buttoned-down bank-manager boss; Rory Culkin as her precocious, flat-affected young son; and in particular Mark Ruffalo as her seemingly burned-out drifter brother back for a visit. Predicated on the give-and-take of the siblings’ dynamic and the pleasing spectacle of each character performing against expectation, ultimately writer-director Kenneth Lonergan’s film is canned—but it’s premium quality canned. With its accomplished, old-fashioned narrative values, richly drawn characters, and incisive, droll dialogue, it justly won the best screenplay award.

Best of the rest in competition? Star Maps director Miguel Arteta and “Freaks and Geeks” and “Dawson’s Creek” writer Mike White’s Chuck and Buck, a kind of inverted Rain Man most interesting for the regressive, homoerotic overtones that develop in its latter stages. After his mother’s death, childlike, emotionally arrested Buck (played by White himself) moves to L.A. to reclaim his long-lost childhood pal Chuck (Chris Weitz), now a yuppie music industry executive. Incapable of moving on with his life, when he’s rebuffed Buck holds Chuck’s sympathetic fiancée responsible and writes a play intended to make Chuck realize how he’s been manipulated, using his savings to produce it. Arteta and White give all the characters their due, and the performances are decent (mention should be made here of Lupe Ontiveros as the seen-it-all theater manager who takes Buck on and directs his play). But the film is pretty negligible, pointless, almost an exercise. Shot on DV, transferred to film, cost next to nothing, looked like shit: cold, fuzzy, and coarse. If that was the point, I missed it. Even after projection goes digital, video will still mostly look dismal and viewers will mostly dismiss it as badly shot until it matches the resolution, latitude, and contrast of film.

Jim McKay’s modest, unassuming Our Song was a vast improvement on his first film, Girltown. This resolutely undramatized slice of life about the friendship of three teenage Brooklyn girls and the everyday dilemmas and choices they face—a pregnancy, a breakup, the temporary closure of their school—has real integrity. Loosely structuring the film around the girls’ high school marching band practices, McKay takes care to give a fully rounded sense of his characters’ lives and the world they inhabit, forgoing all but the slimmest of narratives for behavioral truth. Where Girltown was crudely made, sketchy, programmatic, and hung up on a Mike Leigh-inspired workshop approach that was beyond McKay, Our Song is completely convincing and much more visually accomplished, thanks in part to Jim Denault’s attentive vérité camerawork.

Never let it be forgotten that at Sundance (Institute and Festival alike), PC doesn’t just stand for Park City. As usual, the self-congratulatory/well-meaning fanfare about the greatly increased number of films by women didn’t take account of the quality of the work itself—all it proved was that women are just as capable as men of making mediocre or just plain bad films. On opening night, the Sundance audience was left ecstatic by Bahji on the Beach director Gurinder Chadha’s What’s Cooking?, a crass, contrived tribute to the multiculturalism of Los Angeles—just what we need. Chada breathlessly intercuts between four families (Vietnamese, Black, Jewish, Hispanic) during Thanksgiving to reveal a stacked deck of generational, sexual, and political divisions within each. A gastronomic Intolerance, it’s an unapologetic celebration of matriarchy in which resourceful mothers hold families together in the face of dishonest fathers and disruptive sons, while misunderstood daughters struggle to be heard. Steeped in the kind of false cultural representation that adherents to political correctness do best, this must be the first movie to feature Jewish and Vietnamese families saying grace before a meal.

It goes without saying that the next day Mary Harron’s sensational, sardonic American Psycho was met with a distinctly cool reception. (See my Quickie review elsewhere on this site.)

Howard Rodman’s Joe Gould’s Secret is an account of the real-life relationship between a bemused, diffident New Yorker writer (Stanley Tucci) and a homeless eccentric, memorably played by Ian Holm, who frequented New York’s Bohemian art scene in the 1940s, and whose life’s work was the completion of a vast oral history of the world. Although the uneasy symbiosis of a cultural establishment insider and a half-crazy outsider artist might have been an apt metaphor for the Sundance modus operandi, the film is too lackluster and inconsequential to pack any punch. Director Tucci’s mise-en-scène is too self-regarding and fussy, the just-so period design is stifling, the cinematography arid. An improvement on The Imposters, yes, but it’s no Big Night. Maybe Campbell Scott was the brains behind that one all along.

Ingeniously and divertingly updating Shakespeare to corporate New York (Denmark is now a multinational company, Elisnore a hotel), Michael Almereyda’s Hamlet benefits from playfully iconographic casting: Ethan Hawke as Hamlet, Kyle MacLachlan as Claudius, Bill Murray as Polonius, Sam Shepard as the Ghost of Hamlet’s father. These might sound like semi-parodic one-liners, particularly if you share the widespread dismissive estimation of the admittedly callow Hawke, but the performances are memorably etched and Almereyda plays things straight, even when Ophelia is calling MovieFone or Hamlet is bundled into a cab to be greeted by a recording of Eartha Kitt telling him to buckle up. In contrast to the in-your-face pop culture riff of Baz Luhrmann’s Romeo + Juliet, Almereyda opts for a more cool, detached mode and a clean visual luxuriance, staging things in long, fluid takes, beautifully realized by DP John de Boorman. Like Luhrmann, he situates Shakespeare firmly in the realm of media and technological overload—cell phones, TVs, wiretaps, comical product placement—but goes a step further by linking modern urban malaise and fragmentation with Shakespearean morbidity. Hamlet’s soliloquies are presented in playback as self-absorbed pixelvision video diary musings, and most audaciously, the “To be or not to be” speech is reinvented through dispersal, preempted by a Tibetan spiritual teacher on TV talking about the nature of being, begun as a video recording, completed as Hamlet wanders the aisles of Blockbuster. Still, despite the indie rock soundtrack, the customary Almereyda distracted poetics and visual asides are muted—the film lacks the spark of wonder and strangeness that animates his other films, with their Martian-eye view of human interactions and the workings of the human heart, and his inspiration falters altogether in the climactic duel between Hamlet and Laertes (Liev Schreiber). Although Shakespeare adapts well to a world of penthouse suites, press conferences, limousines, and watchful bodyguards with ear pieces, ultimately the conjunction of original text and modern setting doesn’t resonate or yield new insights into either.

Maybe the final word should go to one of the original indies, still going strong. Alan Rudolph’s Trixie is a delightful mystery/conspiracy thriller genre pastiche, full of his customary inversions, mirrorings, and visual mischief. Emily Watson plays a plucky private investigator who comes to a Northwestern resort town to provide security for a casino. Encountering a typical gallery of Rudolph eccentrics—jaded, booze-soaked lounge singer (Nathan Lane), inept lothario (Dermot Mulroney in the Keith Carradine role), boorish real estate tycoon (Will Patton)—she soon picks up threads of crime and coverup that lead all the way up to a lecherous, cant-spouting senator (Nick Nolte, pulling out all the comic stops as only he can). To keep things lively, Rudolph gives his eponymous heroine a speech disorder that mangles her every utterance with richly comic malapropisms (“Why does everybody have to beat a dead horse to death?”), making a mockery of the hardboiled dialogue and situations. The genre elements (sex scandal/blackmail/murder/shady real estate deals) remain notional, indefinite, teetering on the verge of abstraction. But through the layerings of sentimentality, irony, burlesque, and wordplay, in his own idiosyncratic way Rudolph critiques the debased civics and incoherent politics of the Clinton era, where everybody is on the make and has sex on the brain. It’s all brought off with such consummate ease that Rudolph’s modernism is starting to look classical. And it ought to be the last word on American independent film’s receding infatuation with the noir/crime movie genre.