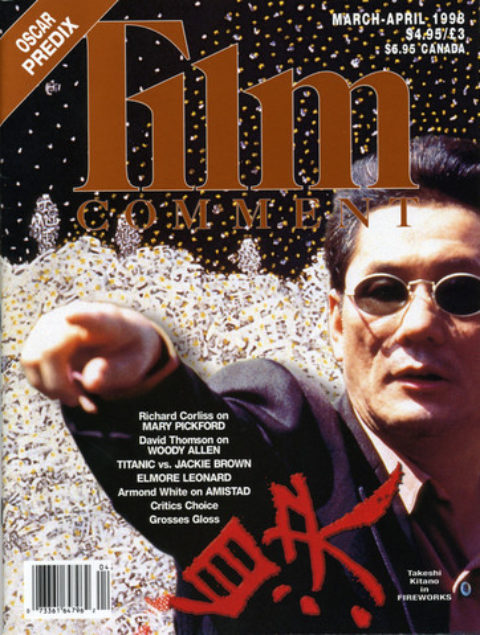

Buffalo ’66

Throw a brick out a window and you’ll hit twenty actors getting ready to direct, invariably citing Cassavetes. After one try, most get it out of their system; others—Forrest Whitaker, Sean Penn, John Turturro—have acquitted themselves honorably while remaining more valuable in front of the camera; recently, only Tom Noonan and Ben Stiller have demonstrated real filmmaking talent. Now I’m adding Vincent Gallo to the list of actors I hope make a habit of directing without giving up acting. Premièring at Sundance this year, Buffalo ’66, which Gallo co-wrote with Alison Bagnall, was arguably the festival’s best film; naturally it went home prizeless—though we’ll name it Film Comment’s Most Promising Directorial Debut for this issue. Destined for love-it-or-hate-it cult status, it’s a genuinely idiosyncratic study in American miserabilism and the redemption of a beautiful loser. The entire film takes place on the first day of freedom for Billy Brown (Gallo), who has just done five years for a crime he didn’t commit. Arriving in his hometown, Buffalo, he kidnaps a surly teenager (the incomparable Christina Ricci) who puts up only token resistance, and bullies her into posing as his wife and accompanying him on a visit to his parents. As he coaches and yells at Layla like a third-rate movie director, it quickly becomes apparent that Billy’s all bark and no bite. Once at his parents’ home, he sinks into stoic resignation when his feeble ploy backfires by succeeding: Mom and Pop (played with barely contained mania by Anjelica Huston and disgusted impassiveness by Ben Gazzara) ignore their son but are enchanted by Layla, who unexpectedly brings more conviction to her role than he to his. Humiliated and filled with impotent rage, Billy departs with Layla in tow. As the latter, herself a lost soul, slowly falls in love with him, Billy revisits people and places from his past, fatalistically preparing to take revenge on the man who was the unwitting cause of Billy’s downfall: a strip-club owner and former Buffalo Bills place kicker whose missed goal cost the ’91 Superbowl, on which Billy had bet $10,000.

Buffalo ’66 supplies an antidote to indie film’s fixation on killer couple road films—this couple don’t kill anyone, don’t go anywhere, and their most transgressive act is a tentative, petrified holding of hands. From the start, Gallo underscores that this isn’t a genre film: fresh out of prison, Billy’s first act isn’t a killing, a theft, or even a fuck—it’s a frantic search for somewhere to take a piss. His story is a comedy of almost cosmic alienation, a steady procession of small indignities and emotional humiliations that builds towards violent release. At the same time, Billy’s hardened-criminal pretenses are stripped away to expose a powerless innocent torn between longing for the tenderness he’s been denied all his life and reflexive rage toward a hostile universe: at one point allowing his act to drop, Billy moans, “Please hold me”—and as Layla readily responds, he recoils, shrieking, “DON’T TOUCH ME.” More than anything the film dramatizes this essential conflict: between sensitivity and brutalization, self vs. environment. The title alludes to the time and place of Billy’s birth (in the middle of Buffalo’s only Superbowl win), underwriting its preoccupation with origin as both curse and perverse source of pride—a poison-pen valentine to “my loser city,” as Gallo put it at the post-screening Q&A. Autobiographical to the extent that it posits a road not taken, the film can be read as a confessional acknowledgment of the insecurity driving Gallo’s own reckless, fuck-you persona. Buffalo ’66‘s aesthetic makeup is plain to see: its romance of character as spectacle is inherited from Cassavetes, evinced by both Gazzara’s presence and Gallo’s uncondescending attentiveness to pathetic, wounded and wounding, even grotesque humanity; while its anti-glamorous poetic appreciation of the mundane and the unapologetically dismal derives from early Jarmusch. Gallo’s wellnigh forensic sense of the textures and registers of working-class stagnation is complemented by a connoisseur’s eye for the almost surreal comic horror pathology of familial dysfunction and emotional deprivation. Billy’s parents are both sealed in their own private worlds; the mother’s is built around a fanatical dedication to the Buffalo Bills and watching tapes of football games long past; the father’s is located in a recessive Lynchian realm of creepy/melancholy reverie, glimpsed in an extraordinary interlude when he entertains his “daughter-in-law” by lip-syncing to a record of “Fools Rush In” (whose original vocal is credited to Vincent Gallo Sr.).

There is a air of intriguing atavism about the textures and contours of Buffalo ’66‘s visual style and tone—partly because it’s shot entirely on 35mm reversal stock, a risky process that produces distinctive color saturation and contrast but is prohibitively difficult to print. Gallo’s unheard-of insistence on shooting reversal suggests both bracingly perverse hubris and an uninhibited naïve-purist art sensibility—qualities apparent also in his consistently eccentric setups and compositions and whimsical use of optically inset frames-within-the-frame (mainly as corroborative flashbacks). But Gallo’s compact yet idiomatic mise-en-scène is nowhere more inventive than in his transfixing staging of Billy’s climactic act of vengeance in the strip club—a sui generis series of mind’s-eye tableaux vivants, lurid real-time freeze frames set, with incongruous perfection, to Seventies-era King Crimson. I’ve never seen anything like it.

Buffalo ’66

With his outlandish glam-sleaze style, restless, narcissistic energy, and unconventional, lupine looks, this palpably uncompromising and outspoken actor seemed doomed to perpetual on-the-verge cult status; fans and detractors alike could be forgiven for imagining a pileup of self-indulgence and excess at the prospect of Gallo directing something. In fact, aberrant as it is, Buffalo ’66 is a work of disciplined, exacting intelligence and rare creative adventurousness, and it completely transforms Gallo’s profile.

It must be said that this was not a great year at Sundance. Yes, the festival made impressive strides in terms of organization and infrastructure. But there was no tingle of anticipation around any of the premières, which, with the exception of Paul Schrader’s Affliction, ranged from the abysmal (selfconscious confections like The Misadventures of Margaret, with its smug, self-aggrandizing references to poststructuralism and Forties comedy, and Tom DiCillo’s sick-making The Real Blonde) to the mediocre (the vacantly arch gangster doublecrosses of Jennifer Leitzes’s labored Montana). Along the way were ambitious disasters (Boaz Yakin’s heartfelt but muddled study of one plucky woman’s oppression in a Brooklyn Orthodox Jewish community in A Price Above Rubies) and moderately watchable trivia (David Mamet’s The Spanish Prisoner, Don Roos’s The Opposite of Sex). As for the core Dramatic Competition, well, last year, out of 18 films, seven were either extremely good or interesting—a reasonable rate of return. This year, it fell to five out of 16.

Aside from Buffalo ’66, the other Dramatic Competition highlight was the arresting, delirious, semi-sci-fi psychodrama π (Pi), which proved that even math can be the stuff of compelling cinema. At once ingeniously cerebral, playfully twisted, and maniacally headlong, this interiorized narrative of obsessive scientific inquiry follows a brilliant, reclusive mathematician as he pursues a Holy Grail of number theory that will reveal the hidden patterns of meaning and order underlying the universe’s chaos. The only hitch: he’s schizophrenic.

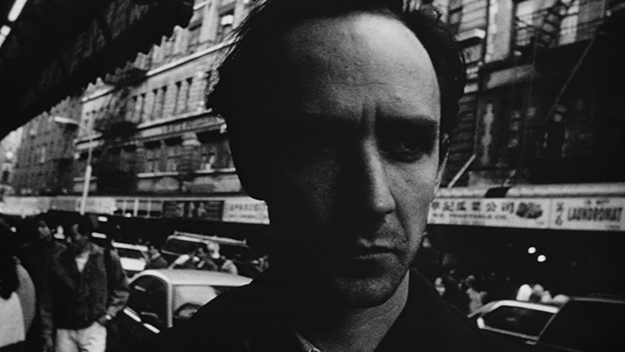

π

Written and directed by Darren Aronofsky, π is an adventure in ideas and interconnection in which everything the main character encounters comes to seem part of a grand mathematical scheme or conspiracy—from his own name, Maximilian, to the spiral form of swirling cream in a Godardian cup of coffee, from the Japanese board game Go to the film’s pulsing techno-electronic score. There’s madness in this paranoiac martyr’s method; probably not since Eraserhead has a low-budget film dredged up so much rich psychic ooze. When Max steps outside the claustrophobic hi-tech disorder of his apartment (unavoidably a representation of his mind), it’s into a strangely other multicultural New York where he is courted, stalked, and then seized—first by shady corporate types who want to put his talents to work on the stock market, then by Orthodox Jewish scholars who believe the Torah is “just a long string of numbers—a code sent from God” that only Max can unlock its mysteries. A tour-de-force of grainy, high-contrast black-and-white photography and inventive editing and sound design, π at times ventures to the limits of cinematic legibility. Too bad it took the intervention of Competition juror Paul Schrader to ensure Aronofsky won the Best Directing prize.

Writer-director Lisa Cholodenko won Best Screenplay for her vivid, acutely observed, but uneven High Art, which probed the romantic codependency of creativity, desire, and self-destruction. It depicts the burgeoning relationship and eventual love affair between Syd (Radha Mitchell), an ambitious but naïve art magazine assistant, and Lucy (Ally Sheedy) a charismatic semi-legendary photographer living in obscurity. A film à clef about noted photographer Nan Goldin, High Art is often compelling and uncannily accurate in its evocation of downtown demi-monde characters and druggy, entropic milieu—the art in this film is high in more ways than one. Cholodenko sets up an aptly nodding, languid style of drifting visuals and has a strong sense of casual-intense intimacy. Taking their cue from the title of Goldin’s first collection, The Ballad of Sexual Dependency, director and cast skillfully mine the emotional and psychic sabotage of malfunctioning relationships for its comedy and pathos. Amongst a uniformly strong cast, Sheedy’s staggering performance is rich with moments of mesmerizing, weary tenderness (a haunting love scene between Lucy and her companion Greta) and aching ambivalence (the quiet agony on Sheedy’s face as Greta searches around for heroin after an overdue, pull-no-punches confrontation).

But the film’s anatomy of the symbiotic relationship between the glamorously decadent integrity of the artist and the glib calculation of the art world establishment stays just this side of cliché, and Cholodenko can’t resist the reductive myth of the artist as doomed fuckup. Though almost an allegory about the processes of cultural shift—the seduction of the straight, rational mainstream by deviant, Dionysian subculture—this scenario of an innocent initiated by a worldly older woman is subtly undercut by the end, and the film implicitly acknowledges the ethical no-man’s-land of appropriating an existing artist’s life for inspiration, even in homage. Still, High Art succeeds in conveying something of the underlying compulsion of an artist like Goldin to wrest art from desire, abjection, and anticipatory nostalgia, to honor and idolize her milieu. And Sheedy’s indelible performance makes the film essential viewing.

High Art

Sundance has continued to expand exponentially, and every year Robert Redford makes his traditional soul-searching, vaguely dissociative speech about the festival’s future and direction. There has been a shift in emphasis: what began as, and nominally continues to be, a venue for the presentation of uncommercial, alternative work has slowly but surely become a marketing/publicity launching pad for films produced or already acquired by the specialty distributors now owned by Hollywood. The fix has been in for some time now. As a media event, Sundance is the perfect place for the industry to present its 100 percent genuine imitation indies. That’s not to say Sundance doesn’t still have an important function as a conduit between the industry and new talent. When Boston filmmaker Brad Anderson brought The Darien Gap to Sundance ’95, critics took note but the industry wasn’t buying. He returned this year with Next Stop Wonderland—modest and competent, albeit lacking the nervy stylistic rawness and bite of his uneven, undistributed debut. Miramax confirmed his commercial arrival with a $6 million deal for the film and Anderson’s next two. People nodded sagely at Miramax’s investment in talent.

Still, Next Stop Wonderland, unlike most of the rest of the films this year, had an actual aesthetic agenda. Its conceit is to revitalize a stock romantic comedy premise (will-girl-meet-boy?) by largely discarding the genre’s standard-issue glossy contrivances and pat charm for a stripped-down, unembellished naturalistic style and tougher, more self-aware sense of personal dilemma and frustration—gritty romance, maybe. In Anderson and Darien Gap writer-actor Lyn Vaus’s scenario, a whip-smart, average-neurotic underachiever working as a hospital nurse (Hope Davis of The Daytrippers) searches in vain for her match in intelligence and sensibility. And he’s out there sure enough: a sensitive, thoughtful ex-plumber (Alan Gelfant) studying to be a marine biologist and struggling to break free of the limitations and pressures of his blue-collar background. Their lives crisscross, but never glibly, and messy situations aren’t resolved by cute dialogue and easy charm—for once we’re given reflective grownup characters, unsentimentally but affectionately observed in the Cassavetes spirit. There’s much comic pleasure to be had, notably a hilarious montage of scary blind dates, and the unobtrusive plotting, adroit direction, alert photography, and fleet editing all conspire to make Anderson’s film a beguilingly honest look at romantic longing.

Next Stop Wonderland stood head and shoulders above a Sargasso Sea of negligible, often limp romantic comedies that infested the festival. Was this a kindler, gentler Sundance then? The festival was in need of a dose of irresponsibility or dissonance, but Sundance’s hothouse audiences long for sheep in wolves’ clothing – films that come on like risky alternative visions but prove to be safe, heartwarming We Are the World affirmations. That would be director Chris Eyre and screenwriter Sherman Alexie’s insubstantial Smoke Signals, which pandered like crazy to the PC crowd’s thirst for anything Native American, no matter how mediocre. An indifferently directed road-movie evocation of oral tradition, constructed from anecdotes, memories, and reminiscences, it’s crammed with Deep Thoughts, fortune-cookie epiphanies, and laboring-to-be-offbeat comic observations about cultural heritage, sons coming to terms with dead fathers, etc., complete with “poignant” ending. The crowd I saw it with lapped it up and, sure enough, it won the Audience Award—and more disconcertingly, the Filmmaker’s Trophy, awarded by filmmakers attending the festival.

Slam

In the same vein, though certainly much better, was the Grand Jury winner: Slam follows the fortunes of a Washington, D.C., street poet in the wrong place at the wrong time who gets sucked into the criminal justice system. Inspired by a female poet who teaches a prison writing workshop, he emerges from jail to pursue a relationship with her and experiences a hazily defined moral and artistic crisis in which acting workshop histrionics get the better of any rigorous analysis of characters, relationships, or circumstances.

The poetry performances have a certain ferocious conviction and momentum, but director and co-writer Marc Levin doesn’t contextualize the protagonist’s poetic practice at all (not even in terms of hip-hop), as if he exists in a cultural vacuum. Nor does the film have any real inkling of how spoken poetry functions as a tool for negotiating or processing intractable social and personal realities—other than as the most obvious form of catharsis. Moreover, suffused with an emphatic but completely vague sociopolitical anger, Slam can’t get beyond reiterating familiar sentiments about genocidal cycles of violence and black male prison statistics.

Writer-director Tony Barbieri’s One was inexplicably sidelined in the American Spectrum program. Not particularly commercial but full of unprepossessing integrity, it’s a terse, economic portrait of defeated masculinity, the deadening weight of past failure, and the limits of possibility, as refracted through the shifting, at-times-antagonistic emotional interdependency of two childhood friends, each attempting to recover from crushing blows that have blighted and stigmatized their adult lives. Embittered, unreflective Nick (Charlie Picoy) is a failed major-league baseball player masochistically resigned to a career as a garbageman; subdued, introspective Charlie (co-writer Jason Cairns, a dead ringer for a young Christopher Walken) is a parolee who served time for the assisted-suicide manslaughter of his grandfather. While the withdrawn Charlie attempts a faltering social reintegration and nurtures altruistic aspirations, the ostensibly functioning Nick remains locked into aggrieved, antisocial self-interest. Barbieri explores their relationship with insight and clarity while turning the film’s limited means to expressive advantage—the spare, stark mise-en-scène, indifferent art direction, and pale, muted color scheme finally embody the repression of the film’s characters. But though both actors are good, the film is dependent on a level of nuance that at times eludes them and their director. One‘s stubborn resistance to dramatic artifice, its deliberate pacing and unexpressive—or rather, unemphatic—naturalism, leave it teetering on the brink of vapidity. Yet compared to a high-profile failure like A Price Above Rubies, which doesn’t show even a rudimentary grasp of story and character, it’s refreshing to see a director get the basics right. Barbieri is an unmistakable talent who should go far. One, for all its flaws, represents the kind of filmmaking that should be Sundance’s raison d’être: its exclusion from competition was little short of absurd.