Hollywood at the Barricades

Trumbo

As close to an intervention as any studio film in recent memory, Adam McKay’s The Big Short minces no words in explaining how the 2008 financial crisis went down—and wields Wall Street jargon and numbers with a precision that is unprecedented. It’s not the sort of thing you see on American screens outside of documentary, but it also wasn’t the only film this year to reflect a certain openness about the grimmer realities of American politics and economics that are usually acknowledged only grudgingly or vaguely if at all. It’s not every year that you have a major motion picture with a Communist protagonist as a hero, for example, but there was Trumbo, laying out the sins of Americans past against freedom, with the hokiness of an old-school biopic. And 99 Homes attempted something similar to The Big Short with its nearly didactic story of a broke single dad (Andrew Garfield) tempted by the devil—in the person of Michael Shannon’s real-estate crook at the height of the housing boom, featuring a shrill speech about America belonging to the winners. And then there was Our Brand Is Crisis: David Gordon Green’s tale of political consultants engaging in outright duplicity and deep cynicism, in a small South American country’s presidential campaign. It seems an attempt at screwball, but when riots erupt in the street once the IMF-crony establishment candidate is elected, the come-down from the usual movie-magic is hard to ignore.—Nicolas Rapold

Leaning In and Making Bank

The Hunger Games: The Mockingjay Part 2

Discrimination against women and minorities in the movie and television industries is hardly a new story. Back in 1983, the DGA filed a class action discrimination suit on behalf of its female and minority members against Warner Bros. and Columbia. That suit went nowhere, but this year the Equal Opportunities Commission and the ACLU both got involved in investigations to support legal actions. The possibility of court cases, tied to the habitual low numbers for days spent in the director’s chair by women (still far below 10 percent for Caucasian and minority women together, slightly above that for minority men according to the newly published DGA survey for 2013-14); the willingness of major female stars such as Jennifer Lawrence to go public about being paid less than their male co-stars; and the years of dedicated work by the Geena Davis Institute on Gender in Media and the Center for the Study of Women in Television and Film at San Diego State have paid off in a torrent of news stories that might produce change. Since industry mindset is a function of the bottom line, the fact (as Manohla Dargis noted in The New York Times) that Universal, whose releases included three female directors and a lot of on-screen diversity, scored 24 percent of the total market share of the six big studios as of December 1, is something that might put front offices on notice.—Amy Taubin

A Cure for the Green Screen Blues

Mad Max: Fury Road

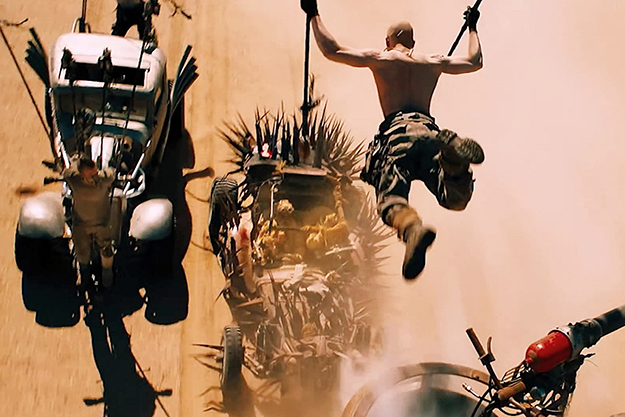

You can’t fake a rock, said Stanley Kubrick, because every real one has a logic of its own. The same can be said of every stick of wood and every drop of water. But in vast swaths of industrial moviemaking, everything seems to consist of the same insubstantial substance. Computer-generated imagery is a remarkable tool that was very quickly and widely exploited as a shortcut to epic grandeur and, finally, to basic moviemaking. Since 2002’s Star Wars: Episode II – Attack of the Clones, a CGI milestone, we’ve been treated to acres of computer-generated tidal waves, fireballs, massing armies, physics-defying chases and transformations, and monotonously “inventive” conflagrations—taken altogether, a nonstop diet of low-cal images that has come to exert a curiously lulling effect on the viewer. So while it may be unsurprising to see a growing number of filmmakers turning in the opposite direction, the development is still both welcome and wondrous. On the one hand, we have the examples of László Nemes and Quentin Tarantino (employing a bare minimum of CGI effects) shooting, finishing, and, when possible, projecting on 35mm and Super Panavision 70 (complete with overture and intermission), respectively. But we also have two more defiant and dramatic counterexamples. Mad Max: Fury Road and The Revenant each have their share of CGI, but they are both solidly based in the real physical world—of real physical stunts on real trucks really moving at high speeds on the one hand, and elaborate action staged in truly untouched stretches of wilderness on the other. Both films return us to cinema’s origins, and posit a possible alternate future for the action genre.—Kent Jones

The New (Para)Normal

Scouts Guide to the Zombie Apocalypse

Three things are certain in this life: death, taxes, and anxiety over the distribution of popular entertainment. In the Forties, Golden Age Hollywood’s obsessive grip on how, when, and where we see our movies proved its undoing; in the more than 60 years since the Supreme Court ended the studios’ monopoly over distribution and exhibition, theater chains have maintained a détente with the studios. Now, these studios are increasingly turning their attentions to television networks and online platforms, and it’s causing exhibitors to dig in their heels. The release of the latest entry in Paramount’s hugely profitable Paranormal Activity series is a case in point. In recent years this franchise has been one of the surest things in the business. The films feature no stars; a built-in aesthetic predicated on the use of lo-fi cameras; and they require little to no special effects to elicit screams from thrill-seekers. Nevertheless, the seemingly impossible happened this Halloween: Paranormal Activity: The Ghost Dimension flopped, and not because of fickle teens. Paramount had announced over the summer that they struck a deal with theater chain AMC Entertainment to make the film (along with another genre cheapo, Scouts Guide to the Zombie Apocalypse) available digitally just 17 days after the end of its big-screen run, thus minimizing the traditional window. In response, other major exhibitors, such as Regal and Cinemark, refused to carry the film; its resulting opening weekend gross, $8.2 million, marked the first time a sequel in the series didn’t make back its budget in the first three days. The whole thing may sound like a tempest in a teapot, but it speaks volumes about how resistant the industry continues to be to inevitable change. It’s all about control, and, as ever, no one wants to relinquish it. No wonder delivery services like Amazon and Netflix—with Chi-Raq and Beasts of No Nation, respectively—are slowly evolving into production companies.—Michael Koresky

Final Fantasy

Virtual reality is on a roll, and 2016 might be the year that the smart money gambles on it having wider applications than game culture. On the other hand, if the cameras don’t get better soon and a 360-degree editing language isn’t developed, it might go the way of the hologram. Stay tuned for Sundance’s New Frontier VR showcase and of course for The New York Times’s attempt to prove its digital worldliness with those cardboard VR glasses, which hooked to a mobile app can make you believe you are inside a Middle Eastern refugee camp. Let’s just say I have moral concerns when journalistic empathy relies on the sensory immersion of gaming.—Amy Taubin

Our Doc Could Be Your Life

Amy

Last year may represent a watershed for, to coin a phrase, the Direct Access Documentary, in which famous people speak to fans in their own words/audio journals/home movies, with cinema verité simply acting as a beyond-the-grave conduit (see Kurt Cobain: Montage of Heck, Amy, Listen to Me Marlon). But the bigger trend is that this was the year in which fan-service ideology not only underwrote such confessionals but hit Oprah-like levels of largesse in terms of music docs: devotees of grunge icons, you get a movie! Disciples of R&B/soul legends (Nina Simone–vintage or Amy Winehouse–modern), you get a movie! And lovers of D.C.’s hardcore scene and hip-hop’s favorite drum machine, you each get one too! In the same way that online culture has become niche-driven, the world of docs overall is now overrun with choir-preaching to political factions, social-issue activists, et al. But thanks to Kickstarter, DIY-friendly film fests, and the Tribble-like proliferation of cable networks/streaming services, it’s not just easier than ever to make a movie on Elliott Smith, underage Brooklyn metalheads Unlocking the Truth, or New York’s Seventies Latin Boogaloo explosion—it’s easier to find your exact audience for it. In the future, every musician will be famous on screen, big or small, for 105 crowdsourced minutes.—David Fear

Celluloid Holdouts

The Hateful Eight

What does it tell you when an audience applauds upon being informed that the film they’re about to watch is being projected in 35mm—as they did in a packed thousand-seat New York Film Festival screening of Brooklyn this fall? (John Crowley’s film was actually shot digitally—but it’s the thought that counts.) And what does it mean that Quentin Tarantino used his clout to shoot The Hateful Eight on 70mm and The Weinstein Company has used its (waning) clout to convince exactly 100 U.S. movie theaters to install or dust off 70mm projectors? If it’s a King Canute gesture, it’s certainly an expensive one. There are still plenty of people—beyond the cinephile core—who would rather watch a faded and scratched print of a film than its pristine DCP transfer. Call it movie magic. In the post-digital conversion era, despite the increasing scarcity of prints, theaters with a repertory component have become a boom industry in New York. In 2016, the brand-new Metrograph theater will open on the Lower East side, and Village art-house theater The Quad has been refurbished and will reopen in spring 2016. Both will have 35mm capacity and a repertory-programming component. Not far behind there’s the long-in-the-works Alamo theater opening in Brooklyn, and the IFC Center, which is poised to expand the number of screens and ramp up its repertory programming as well. The loop may never close between filmmakers like Spielberg and P.T. Anderson who keep shooting on film even though the end use is a DCP, and the many, many die-hard exhibitors who still believe in the romance of celluloid—but if film is dead, Long Live Film.—Gavin Smith

Street Knowledge

Chapter & Verse

The cops don’t come out smelling like roses in either Spike Lee’s Chi-Raq or Jamal Joseph’s Chapter & Verse, but both filmmakers do something that’s unusual in the Black Lives Matter discourse: use their insider positions to critique black-on-black violence, mostly gang-related. Lysistrata doesn’t translate easily to 21st-century Chicago and the idea that women’s power resides in their booties makes me a bit queasy, but wrapping an urgent message in irresistible entertainment is Lee’s game and it’s audaciously played here. Chapter & Verse (no distribution yet) is the first fiction feature by Joseph, a writer and documentarian, who draws on decades of community organizing in Harlem to shape a low-key, heart-wrenching depiction of the struggle of a former gangbanger to keep a teenage boy from being forced to prove himself with a gun.—Amy Taubin