Star Drek

Star Wars is the Tom Jones of 1977. Critics who believe analysis belongs on the couch love it; the audience which made science fiction the last pulp genre has led the lines to a box-office smash. The survival chances of Star Wars, on the other hand, are slim. The film defeats serious consideration. No matter how one looks at it, George Lucas has not only made a movie which is mindless where it would be mind-boggling, he has made a movie which is totally inept.

Never mind special effects. If you’ve seen one plastic starship you’ve seen them all. As for midgets in cute-suits, who remembers the amputees in Soylent Green? Consider instead the laser-sword which Lucas painfully spends forty-five minutes defining as an elegantly human weapon, emblematic of the life-sustaining Force. Not only is there nothing elegant, much less exciting, in the light-sword fight between Lord Darth Vader (David Prowse) and Ben/Obi-Wan Kenobi (Alec Guinness), but Luke Skywalker (Mark Hamill), the Force’s young receiver, never gets to use the thing at all. Lucas has painfully constructed a payoff which never arrives.

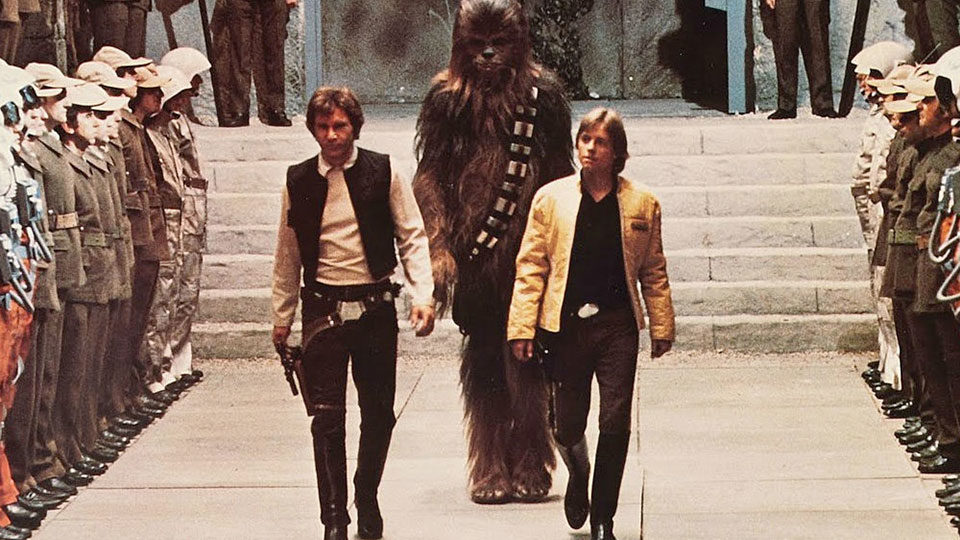

The same is true of the movie’s major climax, the race between Luke and Vader to see whether the rebels or the imperials will blow the other up first. The scene represents an act of skill on Luke’s part (he’s got one shot which must be right on target), a sky-chase on Vader’s side, and a moment of redemption for Han Solo (Harrison Ford), the mercenary smuggler who makes a last-minute decision to look out for Luke and not just himself, thus saving Luke from Vader.

Not only does Lucas blow the impact of Luke’s act—it’s so technological it’s completely removed (why not use the already symbolic laser-sword?)—but the chase is so devoid of spherical geography it is impossible to tell if Luke is really in danger or exactly how Han saves his friend.

And that’s just entertainment. When it comes to extending the genre, Lucas hasn’t done a thing. Consider Luke’s return from the desert to find his surrogate parents blown away by an Imperial raiding party. The shot itself is a direct quote from The Searchers and, one expects, a particularly relevant quote at that. Martin Pauley’s discovery of his massacred family not only occurs after a diversionary chase through a desert, but it forces Pauley to begin the redefinition of family which lies at the heart of that film.

Luke’s encounter should mean something. In the desert, after all, he has met Ben/Obi-Wan, the man who becomes his second surrogate father and who gives him both a true history and a heroic future. Luke has been searching for a connection to his father’s life, but he is afraid to follow Ben/Obi-Wan since it means abandonment of his aunt and uncle at harvest time. The two surrogate fathers are in serious opposition—by choosing one, Luke must disown the other.

But unlike The Searchers, which Lucas quotes, the death of Luke’s “family” causes neither pain nor a confrontation with difficult decisions. Rather than raising problems, it solves them. With his old surrogate parents conveniently killed off, Luke can follow his new surrogate father to the ends of the universe. Between good and evil is an easy choice.

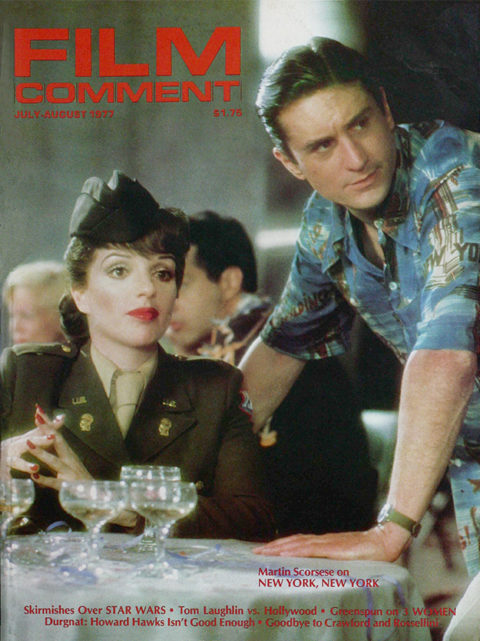

Even more revealing is the film’s end quote—a hero’s welcome for Luke, Han, and company, which is a direct lift from Leni Reifenstahl’s Triumph of the Will. Although there is talk about the death of a “republic” and the dismantling of a “senate,” the alternative in Star Wars is at best a parliamentary monarchy. Not only does this world rely upon heroes, it is devoutly subservient to Princess Leia Organa (Carrie Fisher). The rebel forces seem to want restoration, not revolution.

This is not an idle ideological complaint. Unlike the detective novel, science fiction has yet to find its Hammett. Of the current generation of writers, only two, Roger Zelazny and Samuel R. Delany, are inherently interesting because of their style. From H P. Lovecraft’s Cthulhu to Frank Herbert’s Dune, SF is a genre whose strength comes from its imaginative powers, its ability to create societies in which alternative laws of action and behavior can be displayed.

Lucas, who was so successful at creating a social structure in both THX 1138 and American Graffiti, seems here to have abandoned his most interesting talent. Subsumed by technology, he’s lost control not only of his mechanics and metaphors but of his vision as well.

Examine, for a moment, the much praised robot comedy team of C3PO (Anthony Daniels) and R2-D2 (Kenny Baker). Like the spelling out of their names, See Threepio and Artoo-Detoo are in the throes of what Travis McGee calls “the terminal cutes.” They’ve got everything but fur—everything, that is, except the ability to comment on human activity which makes real comedy teams (not to mention better anthropomorphizations) worthwhile.

Unlike HAL in 2001: A Space Odyssey the robots of Star Wars are not the most human characters in the film. They are exactly what they pretend to be—mechanical figures endowed with a limited number of human characteristics. Like the dog with which W.C. Fields refused to appear, the robot-comics reveal nothing: they exist solely to steal scenes.

The fun-fun-fun brigade claims this is just the point. Looking at the movie closely is like throwing water on the Wicked Witch of the West—so why make it dissolve? Because Lucas has (or had) more potential and, box-office records notwithstanding, so did the film. I’d rather spend my time with a Barry Smith Conan the Barbarian. Smith is in control of both his material and medium; Lucas is not.

2001 had acid. What’s Star Wars’s excuse?