Obedience Training

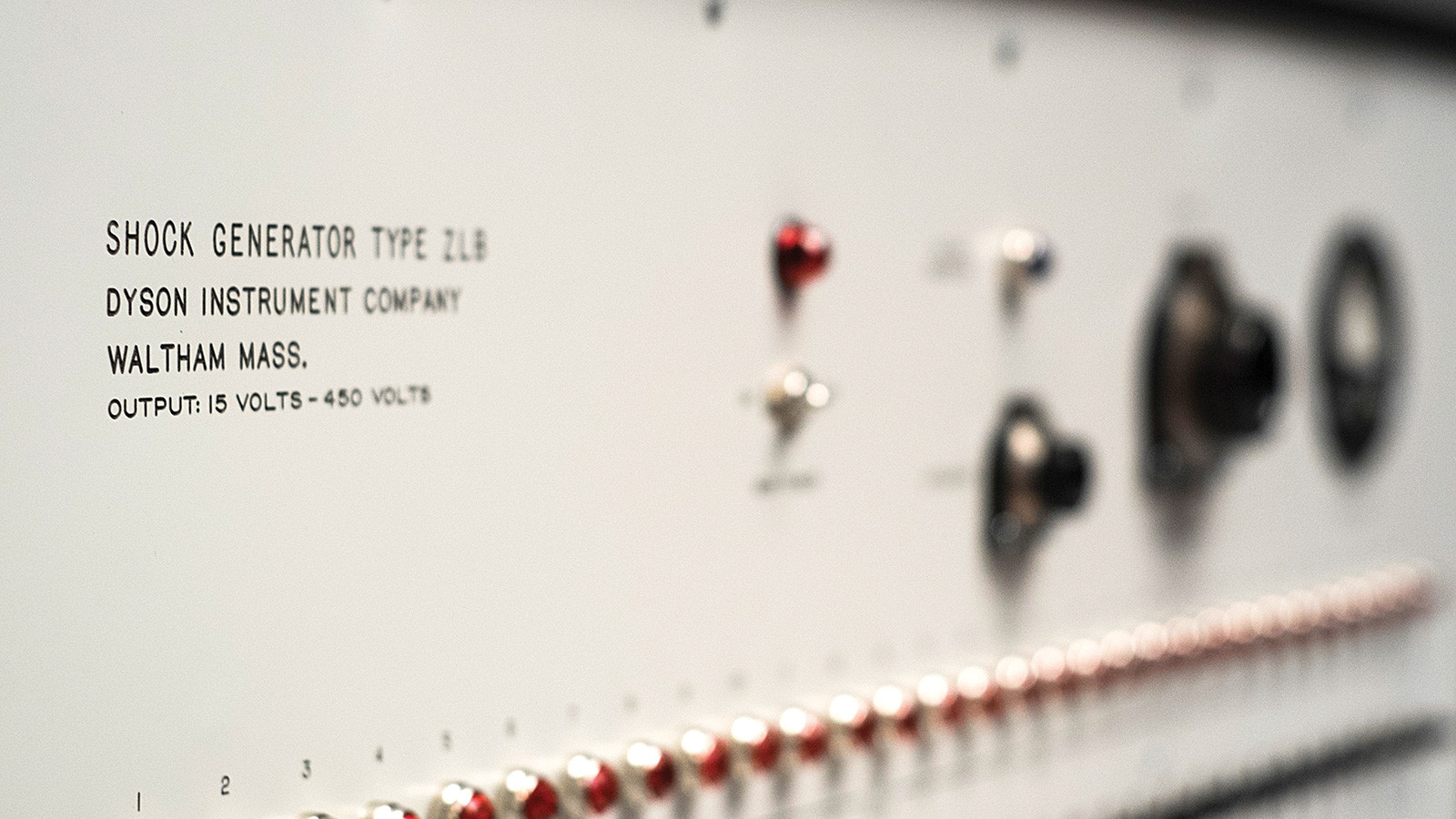

In the early Sixties, at Yale, a social psychologist named Stanley Milgram conducted several subtle experiments in conformity. They established one of the cultural gotchas of modernity, for they concluded that we—human beings—were prepared to do casual harm to others, to behave badly and without humane responsibility, if we could be persuaded that we were being obedient, doing as we were told, following orders, and playing our part in a prescribed show.

That lab work is classic now, though still in some dispute; in its day, it felt so alarming that Milgram was denied tenure. The 1974 book that resulted from that work, Obedience to Authority: An Experimental View, was criticized, notably in The New York Times, which then took our obedience on trust; but it was praised, too, and nominated for awards. Milgram’s conclusions do not go away; they bite more deeply in an age when we feel increasingly helpless or powerless with our decisions. Now here comes a movie based on Milgram’s work, and it is hard not to be troubled by it. Especially if you are inclined to hope that movies are important, or more important than their subjects. (And of course, as moviegoers, we also know what it means to watch under orders.)

The film is Experimenter, by Michael Almereyda, and it is as enchanting but disconcerting as the amiable elephant that sometimes follows our hero in his privileged corridors. At the least, it is a film that studies us and our response with the same detached yet doubting attitude of Peter Sarsgaard’s melancholy, faintly Mabusian and mysterious Milgram. I’d say it’s a remarkable film—as in, one you must see—but it’s more than that.

Experimenter

Let’s begin with two fellows arriving at Milgram’s laboratory one day. They are a jolly couple—Miller (Anthony Edwards) and McDonough (Jim Gaffigan); though strangers, they seem made for each other. They dress similarly, and neither of them is what you’d rate as a “lead.” It’s easy to think of Laurel and Hardy: McDonough is plump, fussy but assured; Miller is lean and anxious. Their rhythms work in unspoken concert. Yet these are not a true pair, or not on the same footing. It is often our sweet dream that actors are enjoying a “chemistry” that has them working for us. As if chemistry was a matter of choice, instead of conforming to fixed, organic rules.

So these two men seem to arrive as equals to the experiment (and its odd model of cinema); the luck of a draw will determine which one will be “Teacher” and which one the “Learner” in Milgram’s obedience test. But that presentation is a setup: Miller has already been chosen to be the Teacher, who asks the questions and administers the electric shocks when the Learner gives incorrect answers. Miller’s worry will deepen as this unnerving game show goes on. Whereas McDonough knows the script in advance. He has pre-recorded his pained responses to the shocks. He is acting; Miller is conforming to his insecure being.

You could argue that Experimenter is a biopic. The film is researched in great detail, even if it feels like a dream. Milgram had a wife, Sasha, and two children before he died of a heart attack at the age of 51. The widow is alive still, and there is a fond close-up of her at the end of the film, which we can file with the images of Winona Ryder, who plays her. Equally, there is a glimpse of the real Milgram walking down a New York City street, enough to show that Sarsgaard has made a good-faith attempt to resemble the real experimenter and to put on the beard Stan had at CUNY.

But Stanley and Sasha Menkin Milgram are not characters for whom Sarsgaard and Ryder are asked to make a journey of inquiry, like Brando and Vivien Leigh digging into Stanley and Blanche, or like the “great” characters in “realistic” films. The Milgrams are figures and images, representatives of real people but without much faith in naturalistic substance. When we first see Sasha, the idea of her as a person is less pressing than the schematic doubling of her image: she is standing back-to-back with her own image in an elevator mirror. In turn, that format is an extension of the experimental setup, where Teacher and Learner have their own adjoining cubicle spaces, with both of them fixed on the blank screen and the sound track pregnant with pain that separates and fuses them. The side-by-side spatial alignment of their adjacent “movies” is augmented by Milgram himself as a foreground figure watching them through a one-way mirror on the screen of science (and subterfuge, for they do not know he is watching—does that remind you of anything?).

Experimenter

To be sure, we see the Milgrams meet, marry, and become parents. She helps him in his work. Still, they are not the kind of lovables we know and identify with from regular biopics so much as figures in a screenscape. When they go to visit the home of Solomon Asch and his wife, there is a shot of the two of them in the front of their car that is emphatically a Hitchcock arrangement of apprehension, a harsh moment, and a back-projected road. When they reach the Asch house, they step out of the car and stand in front of a projected black-and-white image of the country house.

Throughout the movie, Almereyda reduces the possibility of cinematic actuality to a diagram in which behavior yields to transaction. The players are not so much required to act as exist in flat space. So in that first car shot, Sasha’s life or nature has been reduced to the edgy affect of Ryder with her eyes staring and her hair tightly drawn back from her head. She represents fear, without any particular cause of anxiety being explored in the scene. Nothing explains why this marriage is so uneasy—unless we are meant to understand the implication of that elephant in the corridor and the underlying message of Experimenter, that humans are no longer the appealing pilgrims of narrative but the blunt QEDs of social psychology, which is so much easier than having to deal with a divided self or unfulfilled desire.

I know, that sounds grim, or depressing; it’s why I have invoked a doctor like Mabuse and a director like Fritz Lang. But haven’t you been wondering for some time whether narrative texture is ebbing away and returning us to the cold lucidity of Lang? Isn’t that how the clear-cut depiction of the experiment at the outset of this film serves to define the nature of film where, in watching human beings act and react, we run the risk of losing touch with humanity? (While assuring ourselves that we have been “deeply touched”?)

Milgram was Jewish, and with a little archival footage of the famous Sixties glass-booth trial of Adolf Eichmann, Experimenter establishes the Nazi SS as another prompting elephant that leaves our doctor wary. His experiment was hardly needed to confirm that the practice of genocide could be researched, managed, and applied with maximum diligence—amounting to an appalling cruelty. Yet it seemed foolish or indulgent even to bother with a homily like “appalling cruelty.” How long are we appalled before habit sets in? What’s more to the point as a lesson of the Holocaust is that the majority of ordinary people will go along with it and carry out orders.

Experimenter

If the Nazi leaders were exceptionally inventive and industrious in the ways of cruelty and genocide, do not kid yourself that the German people were unusual in their compliance or self-deception. Such traits wait in all of us, especially in a can-do nation. It’s just a matter of luck which side of the equation history assigns you. The real horror of the Holocaust is quiet and commonplace—it’s realizing it could have been us, and knowing the “crime” is beyond punishment, outrage, or intervention. It was human.

But there’s a further snare in this very cool film, which is to see that cinema (by which I mean the crucial separation of reality and spectator) is a system that supports the outrage. You see, obedience is part and parcel of moviegoing. What better model is there for the helpless allegiance of the moviegoer to the ongoing avalanche of film—killing here and raping there, if you can tell one wow from another—than the gravitational pull by which humans do the socially obligatory thing? Isn’t the rapture of watching film—the height of suspense—the way we would sell our soul to be there for what happens next? Nothing is as poignant in Experimenter as the woeful looks the Teachers throw over their guilty shoulders begging to be rescued from the designated task of flipping the switch in punishment. (Truly, Stan and Ollie at Auschwitz could be quite a flick.)

This last paragraph may bring pain and confusion to cinephilia—though the steadfast admirers of so many of our manly directors may worry that the “stunning” beauty in some of our murderous adventures has to be artificial or contrived for “fun” to register. Moreover, have the types of screen we have erected in our minds detached us from the nakedness of experience itself, until nearly everything takes precedence as a filmed event, as opposed to a thing in itself?

Experimenter

This movie seems a radical step for Almereyda, and more attentive to the nature of the medium than anything he has attempted before. So Experimenter could be angry about human nature, horrified and dismayed by its own point, just as once upon a time such a biopic might have been pained that the wisdom of Stanley Milgram was not recognized—as if it really needs to be named and established still when it is an unstoppable process indifferent to our recognition. But Experimenter is not an angry film, and so it exceeds the limits of even Lang who knew he could only portray the machinations of Dr. Mabuse by saying what a very bad man he was, so death and destruction fell on Mabuse (so long as he had enough phantom will power to return for a sequel).

The handling of the players is relaxed and assured, like a card trick. No one has “a part” in the old-fashioned sense, let alone a case for motivation or a need to be directed. But there are thrilling passages of presentation, of Bressonian presence, that need no backstory, or back-acting—I’m thinking of John Leguizamo as one of the more troubled teachers, Emily Tremaine as an argumentative and possibly horny student who can’t understand why Stanley keeps his wife in the room typing up what’s being said, and Dennis Haysbert as a lush-haired Ossie Davis in scenes with William Shatner (played with unlikely restraint by Kellan Lutz) taping a TV drama from 1976 based on the Milgram case.

I also note a tall, assertive blonde (it’s the angle at which she stands) who reads George Orwell while waiting for trains and looks like Lori Singer circa Footloose (from that very Orwell year), even though the biologically older Singer appears elsewhere in the cast, playing Mrs. Asch, pouring tea from an elegant silver pot in the photo-ready living room of a tenured professor.

So much comes down to Sarsgaard as Stanley. Until you explore this calm and even playful film, you won’t grasp the daring with which its doctor manages to be rather seductively bored, especially in the confiding chats he gives us—delivered directly to the audience, as he knows we’re there and is too tactful to rub our noses in our weakness for secret confidences—and in the gloomy patience with which he witnesses the drab limits on the humanity project, and the tenure-weighing efforts of career liberals to argue it away. Mercifully, this Milgram is too withdrawn to risk becoming a readily digestible chocolate Oscar winner; he is beguiling, but he resists attachment. Without Sarsgaard’s serene reticence, Almereyda’s brilliant trap would not close on us so tidily or quietly.

Experimenter

I can hear myself saying what an advance this is for Almereyda, and film, in its assured and ingenious exploitation of the limits of having so little money to work with (as if some thrust of “progress” is carrying us all along). The expensive panoply of budget, decor, and “real stuff” turns to vapor in the acid of the film’s bleak gaze. So often Almereyda’s work has seemed adventurous; this feels inescapable.

You will expect a writer now to urge you to see Experimenter—and for you to behave obediently. Won’t do it. If you see this picture, you may jeopardize the illusion that used to be called cinema, not to mention the forlorn routine of festivals and film magazines. Above all, it’s bad for thinking well of ourselves or believing movies can finesse life. So, don’t see this picture. Be obedient?