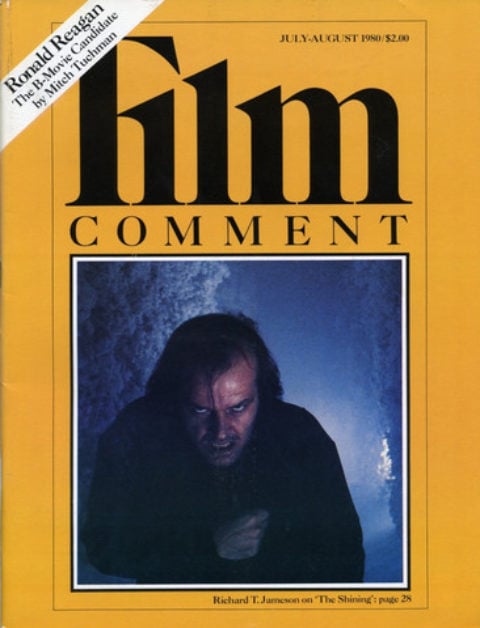

Kubrick’s Shining

The author, who expressed his gratitude to Kathleen Murphy for her contribution to this article, has taken the liberty of discussing scenes that appear throughout the film's narrative. Reader, beware: No one who has not seen The Shining will be seated during the last ten paragraphs. —ed.

Camera comes in low over an immense Western lake, its destination apparently a small island at the center that seems to consist of nothing but treetops. Draw nearer, then sweep over and pass the island, skewing slightly now in search of a central focus at the juncture of lake surface and the surrounding escarpment, glowing in J.M.W. Turner sunlight. Cut to God’s-eye view of a yellow Volkswagen far below, winding up a mountain road through an infinite stand of tall pines and long, early-morning shadows; climbing for the top of the frame and gaining no ground. Subsequent cuts, angling us down nearer the horizontal trajectory of the car as it moved along the face of the mountainside. Thrilling near-lineup of camera vector and roadway, then the shot sheers off on a course all its own and a valley drops away beneath us. More cuts, more views, miles of terrain; bleak magnificence. Aerial approach to a snow-covered mountain crest and, below it, a vast resort hotel, The Overlook. Screen goes black.

Did Stanley Kubrick really say that The Shining, his film of the Stephen King novel, would be the scariest horror movie of all time? He shouldn’t have. On one very important level, the remark may be true. But it isn’t the first level people are going to consider (even though it’s the level that’s right there in front of us on the movie screen). What people hear when somebody drops a catchphrase like “the scariest horror movie of all time” is: You joined the summer crowds flocking to The Amityville Horror, you writhed and jumped through Alien, you watched half of Halloween from behind your fingers, but you ain’t seen nothing yet! And a response: OK, zap me, make me flinch, gross me out. And they find that, mostly, Kubrick’s long, under populated, deliberately-placed telling of an unremarkable story with a Twilight Zone twist at the end doesn’t do it for them—although it may do a lot of other things to them while they’re waiting.

So Kubrick, who is celebrated for controlling the publicity for his films as closely as the various aspects of their creation, is largely to blame for the initial, strongly negative feedback to his movie. Maybe he didn’t know, when The Shining started its way to the screen several years back, that the horror genre would be in full cry, the most marketable field in filmmaking, by the time his movie was ready for delivery. But he could have seen that, say, a year ago. And still he pressed on with the horror sales hook, counting on it—along with his own eminence—to fill theaters, and to pay off the $18-million cost of the most expensive Underground movie ever made.

The action of the film can be synopsized in terms that seem to fulfill the horror-movie recipe. Jack Torrance (Jack Nicholson)—sometime schoolteacher, shakily ex-alcoholic, and would-be writer—signs on as caretaker of this resort hotel in the Colorado Rockies, deserted and cut off from human contact five months of the year. Sharing the vigil will be his quiet-spoken, rather simple wife Wendy (Shelley Duvall) and their just-school-age son Danny (Danny Lloyd).

Danny secretly possesses the gift of “shining”—the ability to pick up psychic vibrations from past, present, and future, long-distance or closer-up. Before he even gets to the Overlook, he gets messages from “Tony,” the make-believe playmate who is Danny’s way of accounting to himself for his special powers. The Overlook has framed its share of bad scenes since its construction in 1907, and more of the same—indeed, some of the same—seem to be in store for the Torrance family.

Jack has no acknowledged powers of shining, but he appears to be in tune with the hotel in his own way. Supposedly, he plans to take advantage of his undemanding work schedule as caretaker to get into “a big writing project” he has outlined, and periodically we see or hear him typing away. But we also begin to get ample indication that he will follow in the footsteps of the previous caretaker, Grady, a steady-seeming fellow who chopped up his wife and daughters one winter’s day and then blew his brains out.

This likelihood is apparent from the first. Among the prime sources of irritation to horror-zap buffs is that Kubrick (writing with novelist Diane Johnson) has thrown out most of Stephen King’s ectoplasmic and otherwise preternatural inventions—most of the more outré ghosts, the demonic elevator, the deadly drainpipe, the sinister hedge animals (an insoluble special-effects problem)—to concentrate on the three principal characters and The Overlook as a collection of abstract spaces.

He has also—and not entirely for reasons of cinematic streamlining—dispensed with virtually all of Jack Torrance’s troubled history, that his “motivations” and the degree of his complicity with whatever forces inhabit the hotel become much more elusive; neither is Torrance permitted a very traceable descent into madness—he simply arrives there. Moreover, Kubrick has decentralized Danny as psychic focus of the action and target of acquisition (because of his gift of shining) for the hotel’s master demons; encouraged Jack Nicholson in the most outrageous displays of drooling mania; and directed Shelley Duvall so grotesquely that Wendy Torrance becomes nearly as much a case for treatment as her husband. He has, in short, deprived the audience of any real opportunity for identifying with his characters in their hour (rather, 146 minutes) of menace, thereby violating conventional theory on how to bring off a jolly good scareshow.

Now it can be told: The Shining is a horror movie only in the sense that all Kubrick’s mature work has been horror movies—films that constitute a Swiftian vision of inscrutable cosmic order, and of “the most pernicious race of little vermin that nature ever suffered to crawl upon the surface of the earth.” The Stephen King origins and haunted-house conventions notwithstanding, the director is so little interested in the genre for its own sake that he hasn’t even systematically subverted it so much as displaced it with a genre all its own. And why should this come as a surprise? Who bothers to characterize Dr. Strangelove as “an antiwar film,” or sees merit in rating 2001: A Space Odyssey as “an outer-space pic,” or finds particular utility in considering Barry Lyndon as a “costume picture”? The Shining is “A Stanley Kubrick Film,” and as such it makes impeccable—if also horrific—sense.

It seems, poetically apt that, at the time Stanley Kubrick was describing arabesques rounds space stations and star corridors and the history of human consciousness in Space Odyssey, Michael Snow was making Wavelength, “the Birth of a Nation in Underground films” (Manny Farber’s phrase). A forty-five-minute film “about” a loft, it consists of a single continuous zoom across eighty feet of horizontal space, beginning with a full view of the room and ending on a closeup of a photograph on the opposite wall. Actually, a dissolve is necessary to get to a second, very brief shot of the photo, which we didn’t even recognize as a photo when the shot/film began: a wave about to break on the shore. Formal pun: Optically move down the length of a room to look at a picture of a wave (the dissolve enabling specific perception and “understanding” after the comprehensive inventory of the whole space)—and the name of this moving picture is Wavelength.

I’ve no doubt that Kubrick has seen Wavelength, and not just because his new film ends with a shot that moves down a corridor and into a photograph, after which we dissolve for still closer scrutiny of the photo’s elements. After all, he appropriated Jordan Belson’s visionary techniques for 2001. And maybe the avoidance of the conventional motivational analysis in his treatment of characters has its analogue in Snow’s cheeky rebuke to our susceptibility to melodrama in Wavelength, when a wounded man stumbles into the empty loft, collapses on the floor, and is summarily lost sight of—and left unexplained—as the zoom penetrates deeper into the room-space, leaving him outside the frame of visibility.

To be sure, Kubrick is a track man rather than a zoom man. Indeed, his tracking—in this film, freed of all physical restraints thanks to the development of the Steadicam—has long since become notorious, if not infamous, among critic types: an obscurely embarrassing fetish. (“Of course, there’s a lot of tracking—he’s Kubrick! So what else is new?)

Nevertheless, the tracking in The Shining is consecrated to a good deal more than satisfying the director’s lust for technology, or providing a grand tour of a Napoleonically lavish set. It personifies space, analyzes potentiality in spatial terms, maps the conditions of expectations with a neo-Gothic environment that is finite, however imposing its scale. And if this sounds like an arid exercise to pass off as popular entertainment, consider that Kubrick twice provides the formal nudge of Roadrunner cartoons heard playing on a television offscreen somewhere. Tell a casual filmgoer that he’s caught between comic and emotional hysteria because Wile E. Coyote’s multifariously misfired stratagems describe a systematic reinterpretation of spatial and temporal possibility, the trading-off of kinetic and potential energy, and he’ll think you’re pulling his chain; but that’s still why he’s laughing.

The Steadycam sits low, mere inches off the floor behind Danny Torrance as he rides his tricycle round and round the ground floor of the hotel early in the film. We follow him for a complete circuit, incidentally getting our bearings on what’s where in relation to what else (kitchen, office, lobby entrance, the Colorado Lounge where Jack does his writing). Kubrick gets away with this establishing tracking shot because even the most antifetishistic observer must find the technical achievement exhilarating, and also because the action is punctuated with one of those vivid, lushly particular moment-of-cinematic-discovery effects that has virtually an atavistic appeal: the clump-whoosh, clump-whoosh sound as the child trikes, with blithe relentlessness, across the polished floor and deep-piled carpet.

Yet even as we get off on this wonderful movement, we look for it to disclose more. Will the kid round a corner and run smack into a ghost? Every turn, every new avenue of perception, is approached with anticipation; and nothing happens. Anticipation, anticlimax, anticipation. It has a lot to do with the quality of the Torrances’ lives.

For Jack Torrance’s life has nowhere to go. The wrinkle in Kubrick’s haunted-house concept is not that The Overlook Hotel, with its layer on layer of sordid, largely silly (in Kubrick’s selection from King) atrocity, taints Jack—it is the setting he was born to occupy, the snow-walled zone in which he can achieve an apotheosis he is clearly unequipped to achieve in any other way. To be a writer, for instance, is not within Jack’s grasp. It is sufficient self-justification that his former wage-earning job of school-teaching got in the way of his writing; or that his wife Wendy so little comprehends the reality of writing (she thinks he just needs to get in the habit of doing it every day) that he can stay points ahead simply by being more sophisticated on the subject than she is. The Overlook’s spaces mirror Jack’s bankruptcy. The sterility of its vastness, the spaces that proliferate yet really connect with each other in a continuum that encloses rather than releases, frustrates rather than liberates—all this becomes an extension of his own barrenness of mind and spirit.

Those spaces draw Jack. Kubrick sees to it that they draw us as well. It’s not merely a matter of corridors obsessively tracked. Virtually every shot in the film (whether the setting be The Overlook or not) is built around a central hole, a vacancy, a tear in the membrane of reality: a door that would lead us down another hallway, a panel of bright color that somehow seems more permeable than the surrounding dark tones, an infinite white glow beyond a central closeup face, a mirror, a TV screen…a photograph. From the moment we lose the consoling sense of focus and destination supplied by that island picturesquely centered in the lake, we are careening through space.

There’s a moment quite early in the Torrances’ residency when Wendy and Danny go to explore the Overlook Maze, a carefully sculpted hedge as old, and very nearly as large, as the hotel itself. Kubrick cuts from them to Jack, drifting in an eerie lope through the hotel interior. He stops at a table which bears a scale model of the Maze outside. A low-angle shot of Jack registering bemused interest is followed by a downward gaze, absolutely perpendicular, at the Maze. This frame is pure geometry—until we notice two figures (cartoonlike or real?) moving, and casting individual shadows, in the central aisle. The overhead view has been descending steadily (camera movement? zoom?) since the cut to it, and faintly, like mouse squeaks, we begin to pick up Wendy-and-Danny voices.

What is the scale here? Are we looking at the table model, or down at the actual Maze? If the actual Maze, those figures are simply Wendy and Danny foreshortened from a great height, as in the opening aerial views of the film; perhaps Kubrick reverted to his fond, God’s-eye view that turns the world into a chessboard. If the scale model, then those figures are grotesque projections of Wendy and Danny—but projected by Jack’s imagination, or somehow appallingly duplicated in demonic, child’s-toy accessory of the hotel. Or is the actual Maze rightly enough, the real Wendy and Danny diminished by distance, being seen by Jack in sympathetic phase with the hovering spirit of the “Overlook” itself? We can’t be sure. Any or all of the above might be true (and the descending view never gets far enough to plug us back into life-sized visual relation to mother and son; this is achieved only by a cut back to them seen from normal eye level). We aren’t sure where we stand in this game, and it won’t be the last time.

In a moment of intense distraction sometime alter, Jack lurches into the hotel bar, the Gold Room, and climbs onto a stool. The place is empty, not only of people (of course…) but also of booze, which the management always removes during the off-season to cut insurance costs. Still, it’s the sort of space in which Jack used to find solace. And now, having awaked from a nightmare of Grady-like atrocity, and having been accused of hurting their son as he (inadvertently?) did once before, he sags with self-pity and sighs, “God, I’d give anything for a drink! Give my goddamned soul for just a glass of beer!”

Up to this point, we have been observing Jack from a diagonal, from behind the bar but some distance down its length. Now we cut to a position directly opposite him. He drags his hands down over his face and then peers straight at us. His face is brightly—to brightly—flooded by the warm glow of a lightning strip built right into the bar; and now the fluorescence is increased by a sudden, hail-fellow-well-met grin. “Why hello, Lloyd!” And Jack slides into a well-rehearsed litany of world-weary wisdom, a soliloquy pretending to be a monologue, delivered to a composite image of all the bartenders in his past. We have been cast as “Lloyd.” The role is bizarre, but not intolerable. Then Kubrick reverse-cuts and there, where we figuratively stood, is Lloyd (Joe Turkel).

Jack goes on talking; he isn’t the least surprised that Lloyd is visible, for real, and pouring him a bourbon, as a matter of lovely fact. We are now the ones distracted. Here at last is an authentic Overlook ghost, vouchsafed to us ever so naturalistically (if eerily gilded by the ambience of the Gold Room) without benefit of any “shining” from Danny. Not only that—we have no way of knowing (and never will know) whether this is the first time in a month or more of occupancy at the hotel that Jack has seen Lloyd. Nor is there any consolation in the fact that, when Wendy arrives on the scene a moment later, neither Lloyd nor his bourbon is in evidence.

Kubrick makes limited, straightforward use of the standard reality-illusion device of mirrors in The Shining; but, as narrative details, the bits and pieces of many different Overlook stories, accumulate, and as the editorial design of the film becomes increasingly oblique and suggestive, more and more one feels trapped in an infinity of facing mirrors. Identity and reference are deliberately confused: Wendy comes to tell Jack, “There’s a crazy woman in the hotel,” and he giddily responds, “Are you out of your fucking mind?!” it is only the first tremor in an extraordinarily concatenation that escalates toward the final crisis.

The brutalization of Danny (of which Jack had been accused) took place in the mysterious Room 237, whose vibrations had tempted the boy several times previously. We watched through his eyes as he passed through the door, but were spirited away by the cutting to Wendy, who in turn led us to Jack, in the throes of “the worst nightmare I’ve ever had,” the gory murder of his family. Hence, though technically innocent, Jack has been formally implicated in whatever transpired in 237. As Jack answers Wendy’s summons to investigate the room, we suddenly find ourselves locked in on the compartmentalized logo of a television news program. A slow zoom-out, and we are in the Miami home of Dick Hallorann (Scatman Crothers), the Overlook’s black cook, who also “shines,” and who had earlier established rapport with Danny in one of those few sequences free (up to a crucial point) of the central-vacancy principle. Reverse-cut and zoom-in to Hallorann as he suddenly registers horror.

Cut to a closeup of Danny Torrance, shivering in a trance, a froth of spittle on his lips (as Jack had visibly drooled when coming out of his nightmare). Then the camera begins describing a subjective penetration of Room 237—Danny shining to Dick about the experience? Dick remembering an experience of his own in 237(his fear of the room having been established earlier)? Not until we see an adult Caucasian hand reaching out to push open the bathroom door can we be sure exactly what is happening.

Beyond the curtain of the bathtub, a hazy figure moves, then draws the curtain aside. A nude woman, young, lovely, but mannequin-like, looks across the room at the camera for a moment—and then we reverse-cut to Jack Torrance in the doorway. The young woman rises, steps from the bath, pauses. Cut back to Jack, who slowly begins to leer in anticipation and starts toward her. They embrace, kiss—and over her shoulder Jack beholds the reflection of a thick, ancient, partially decomposed hag in his arms.

He backs away; she advances, cackling, arms extended. Intercut with this are images of the same old woman seen from above, lying dead in the tub, the beginning to stir to life. It is a perspective Jack never had, but presumably either Danny or Dick Hallorann did; a reality form the recent, more distant past is juxtaposed against the immediate reality of Jack’s experiences in 237 at that moment. Who and which is where and when? And does it matter?

Jack Torrance returns from the encounter denying that there was anything to see in 237. Moreover, he seeks to placate Wendy with the resonant cliché, “I’m sure he’ll be himself again in the morning.” (But he won’t, he’ll be “Tony”.) Wendy isn’t buying; she insists they get Danny out of the hotel. Threatened for the first time with separation from The Overlook, Jack explodes: “You’ve been fucking up my whole life! But you won’t fuck this up!”

Storming off, Jack finds the hotel corridors strewn with balloons and confetti, and the sound of a Twenties dance band floating on the air. A fluid lateral track brings him from the hallway into the Gold Room once more. The night club is filled with subdued revelers in period dress. Jack passes among them, affecting unconcern about his caretaker togs, and adjusting his stride to approximate an elegant dance stroll. Good old Lloyd is on duty, there’s bourbon for Jack’s glass, and “the management” had given instructions that “your money is no good here, Mr. Torrance.” Jack, though unremarked by the assembly as he has surely been unremarked through life, will momentarily be assured: “You’re the only one that matters.”

But The Shining is something much more complex than a simple exercise in solipsism. Lloyd’s respectful salute upon both of Jack’s visits—“What will it be, Mr. Torrance?”—is tinged with quiet irony. And Jack, far from being able to join the party, is instead shunted off from it: a collision with the waiter, a spilled drink, and his and the camera’s course is deflected into…another powder room.

As he has so often played hyperkinetic sequences off against grindingly slow ones, here Kubrick condemns Jack to a long, maddeningly static and formalized talk scene—off the back hall of life, as it were, like the seedy servants’-quarters he is given to occupy in this luxury hotel—while the music and the crowd murmur on the other side of the red, red wall. It is a conversation that self-destructs in its logic: the waiter, Jack’s interlocutor, is none other than Mr. Grady (Philip Stone), the former caretaker, who in short order assures Jack 1) that he has never seen him before, 2) that he himself has no memory of every having been caretaker, 3) that Jack has always been the caretaker—“I should know, sir, I have always been here”—and 4) that he indeed had to “correct” his family when they interfered with his caretaking!

Roles shift in other ways: Grady is the unctuous servant deferring to his superior at the same time he becomes the steely master of the scene and issues the Overlook’s definitive warning that jack is now expected to “correct” his own family. He even introduces Jack to the quaint snobbery of his anachronistic, English-accented cultural frame: Danny has tried to bring “an outside party, a nigger, a nigger cook” into the action; and Jack repeats “A ‘nigger’?” (a superb reading by Nicholson) in a tone that suggests he is not used to considering negritude as an offense, is on the verge of disbelieving laughter, and yet is also fascinated by the new ripple of self-congratulating possibility here. Whose sensibility is in charge? What role does Jack play in the Overlook narrative that would have Grady as its center? Indeed, how many of those other guests out in the night club are “the only ones that matter” in their scenarios—cut off from Jack and from us the way the promising panoply of possibilities in a dream are lost when we detour into a peripheral line of development that never carries us back to the main scene?

Surely this distraction of the self is Hell, not the seamy, vicious gestures by which the lost soul expresses its violence. Jack Torrance is presented with an oneiric environment in which only he matters—and then he doesn’t matter at all. This is the final vacancy. This is the bankrupt script. This is the horror that we feel when Wendy Torrance, come to look for her husband in his den, at last manages to see the Overlook manuscript, the outpourings of his creativities: the endless reiteration, in myriad configurations, of the same formulaic line, the same lyric bad joke—“All work and no play makes Jack a dull boy.” Jack the dull boy becomes Jack the bright boy when, having done murder at last, he rises into a previously neutral frame: this time the vacancy is fulfilled in his wide, white, shining face.

Has there ever been a more perverse feature film than The Shining in general release? No one but Kubrick could have, would have, made it. Certainly no one but Kubrick could come as close to getting away with it. And it is impossible to suggest another contemporary star besides Jack Nicholson who could have served to hold its ferocious strategies together. Both director and star have been widely criticized for showcasing a mugging, transparently implausible geek performance. The devastating subtlety of Nicholson’s Torrance lies in its obviousness. We watch Jack Nicholson—and we will watch Jack Nicholson, note every raised eyebrow, every mongrel twitch of limb—from the fatuous, blatantly phony man-of-the-worldliness and patronizing deference in the opening interview scene (Barry Nelson—a Kubrick casting coup—as the Overlook manager), through the smarmy tolerance of Wendy’s naïveté, to the raging, aggressively self-defensive rationalizations of his contractual eminence in the Overlook establishment. Scarcely a reviewer has failed to sneer that Nicholson has regressed to playing AIP mad scenes—but that’s it, that’s what works: Nicholson the Roger Corman flake become Nicholson the easy-riding superstar, Bad-Ass Buddusky, J.J. Gittes, R.P. McMurphy, super-hip, so sardonically self-aware that he cuts through the garden variety of cynical Hollywood corruption like a laser, and lays back bored.

Jack Nicholson plays Jack Nicholson playing Jack Torrance playing Jack Torrance as King of the Mountain. Everything Jack Torrance says in the extremity of his derangement is pixilated in the viciousness of its banality (“Heeeeeere’s Johnny!”); his loathsome bum jokes are gauntlets of contempt flung in the face of his significant others, his family, his audience—and they are loathsome most of all because they rebound on him, because he tells them badly as he played the furtive madman badly. But not Jack Nicholson. Nicholson plays the badman badly brilliantly.

And Kubrick, the king of his own cinematic mountain, the lone, hush-hush contriver of Skinner boxes for the contemplation of his fellow creatures, or his idea of them? Kubrick flings the stingingest gauntlet of them all. He makes a horror movie that isn’t a horror movie, that the audience has to get into and finish for him.

The Maze: shivers of goose-pimplish expectation from the audience. But no: the Maze is quite benign. Indeed, Danny Torrance knows it like his own hand. Danny the Kubrick Child gets free of bathrooms, slides magically down a personal snow-hill, leads the Daddy Monster a merry chase through that Maze. And the Maze, hole after hole opening before us as the Steadycam rushes down tunnel after tunnel, is not a trap but an escape hatch. Child’s play: Danny backs up in his own footsteps in the snow, nobody else’s; but Stanley Kubrick will not permit the viewer to share in the reversing of relentless tracks.

We stay behind with the monster of banality. We track into the frozen moment of time in a film where time, finally, is as abstract and terrible as space. Once a Kubrick monster threw a bone in the air and became a man; now the man regresses to monster, grunting, incapable finally of even pronouncing its own bad jokes. Illumination is poisonous: we cannot learn: “we have always been here.” The hole—the photograph that the last track penetrates—is the screen. The face grinning imbecilically out at us is our own. Shining.