Genre Collage

In one of his earliest and best-known essays, Sergei Eisenstein described five types of montage, illustrating each with scenes from his own films. The first four types (metric, rhythmic, tonal, and overtonal), deeply influenced by Ivan Pavlov’s study of reflexology, were conceived to trigger distinct physiological effects in the viewer.

Now imagine if you will Eisenstein’s realization that inherent within this methodology was a collusion with the forces making life miserable for himself and his fellow countrymen. The development of his fifth type—intellectual montage—seems a natural conclusion for a troubled conscience such as his.

While intellectual montage generates humor in the hands of experts (Dusan Makavejev, Craig Baldwin), it’s best suited for works of high-minded intent (Eisenstein’s unrealized Das Kapital, Pasolini’s La Rabbia.) So what about other modes of construction, more aligned with the mischievous humor evident in Eisenstein’s drawings and familiar to his friends, but seldom on display in the films themselves? We would have to find the “lost” notebook in which he was seeking just that, formulating a sixth type of montage that deployed physiological means, but with entirely other ends in mind. Call it malapropic montage, the intentional violation of narrative continuity by inserting or assembling shots containing mismatched actors and actions into a cinematic sequence.

If Margaret Thatcher’s face launched a thousand punk bands, Vicki Bennett has for nearly twenty years been part of England’s defiant rear guard or, to use her preferred term, the “avant-retard”. Under the moniker of People Like Us, Bennett has shaken laughter loose from the most tightly-wound of listeners and, in more recent years, viewers. Putting things where they just don’t belong, her prodigious audiovisual output and stateside radio show on WFMU infuse the plunderphonia of John Oswald and The Tape-beatles with the British comic tradition in all its coarse and bawdy glory. Staying true to the principle of “share and share alike”, most of her musical and moving-image output is now available for free download through Ubuweb.

Genre Collage

Her new video, Genre Collage, is currently touring the world as a live audiovisual performance. Produced with assistance from Tim Maloney, it relies less on the layered compositing of much of her previous video work and embraces hard cuts and classical editing syntax. Earlier videos such as Discovering Electronic Music (99) and The Remote Controller (03) drew extensively from Prelinger Archive material and other orphan ingredients, and yet achieved something far beyond the easy camp effects so common among the works of others that tap these sources.

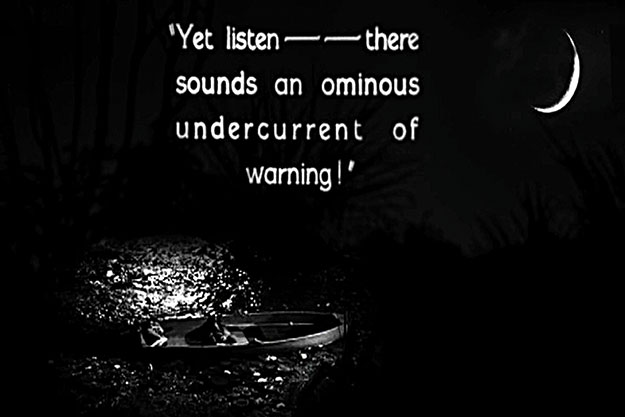

Much of the derisive laughter Prelinger-derived film elicits is the result of a simple disconnect between hope for the future embodied in that material and the failure of our own present in achieving it. Bennett’s work, however, contains something deeper and far more complex in its ambivalence towards technology and social engineering. Shaded with dark undercurrents and self-referentiality, the earlier videos are brought to life by an assortment of recurring motifs: the puppeteer-as-artist-as-God, the orchestral conductor, the graphic artist, and the computer programmer. All serve alternately as stand-ins for the artist herself as well as technocrats responsible for our current state of affairs.

Bits of The Remote Controllerappear once again as part of Resemblage (04). This video, sponsored by London’s LUX, incorporates films from their collection by the likes of Stan Vanderbeek, Larry Jordan, Alan Berliner, and Semiconductor. By using footage from Duo Concertantes and Once Upon a Time, Bennett notably forges an indirect link with Joseph Cornell by way of his former assistant and sometimes-collaborator Lawrence Jordan. Further, Resemblage ignores the unwritten (and seldom violated) rule within found-footage filmmaking—that the avant-garde is off-limits to its own. Inasmuch as the found footage film is itself a well-established genre, a veritable incest taboo has developed within it.

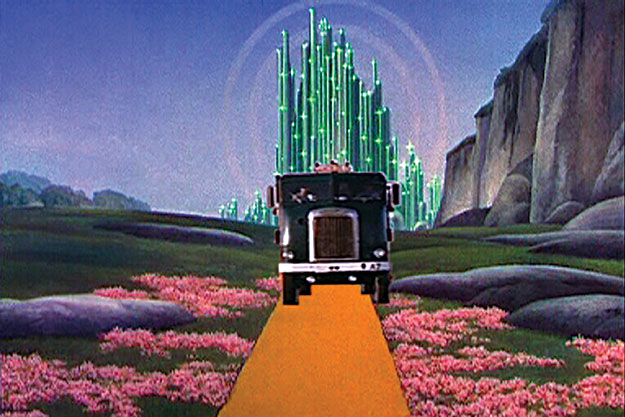

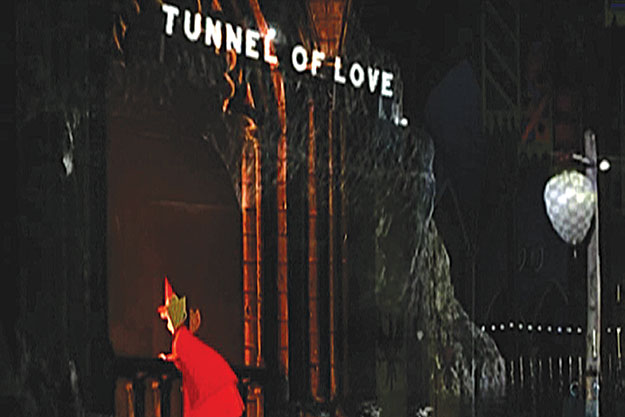

But unlike those earlier pieces (or Bruce Conner’s A MOVIE, with which it otherwise shares strong ancestral ties), Genre Collage draws instead on narrative feature films for its source material––nearly 100 in all. Enter the Dragon commingles with the climactic shootout of The Lady From Shanghai; also appearing are Tobor the Great, The Poseidon Adventure, and plenty of Hitchcock. Peter O’Toole, O.J. Simpson, and Donald Duck are just a few of the many “guest stars”; Mary Poppins pops in as a harbinger of disaster. Its series of twelve loosely connected sequences suggest, but stop short, of an overarching story structure. With each shot—and many are commonly recognizable—comes a memory of their original context. Narrative’s forward motion momentarily seizes before it’s sent careening, malapropically, in another direction. And as with the best of British comedy (be it movies, novelty songs, TV, or the music hall of the past), displacement, class collision, and rude noises are key.

Genre Collage

Malapropic montage stands unwittingly as a testament to the power of Kuleshov’s experiments and, in turn, to the film grammar adopted by, if not invented, in Hollywood. The eyeline match especially is revealed as a nearly foolproof adhesive, and malapropic success might be measured by the degree to which adjacent elements that don’t belong anywhere near each other nevertheless stick.

Eisenstein had initially sought collision in the joining of two shots to complete a circuit and send a shock through the viewer’s emotions; later, his lost notebook seeks in malapropic montage a way of “of effectively circumventing the higher nerve systems of the thought apparatus.” Bennett, in turn, has taken Eisenstein’s montage collisions and refashioned them as bumper cars at a seaside carnival.