Dead Man Walking

Given its extreme content and highly confrontational intensity, it comes as no surprise that Son of Saul has proved controversial. In Cannes, where the film premiered in May, I took part in a FILM COMMENT roundtable of critics; while some of us enthused about the film, Stefan Grissemann found it “highly problematic and also obscene.” Manohla Dargis in The New York Times described Son of Saul as “radically dehistoricized, intellectually repellent.”

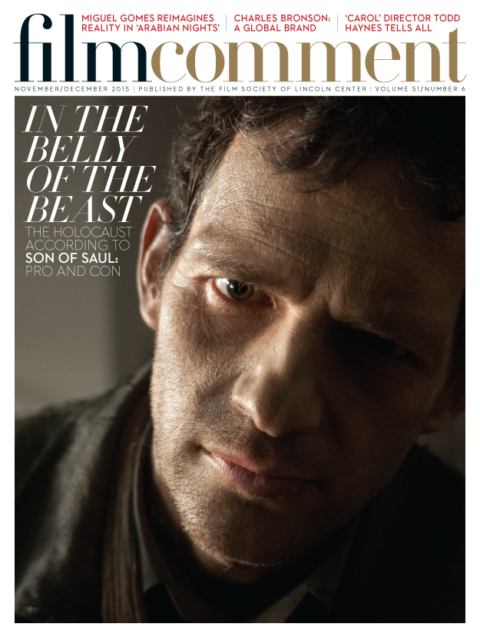

Conversely, Shoah documentarist Claude Lanzmann, famous for his disapproval of dramatic representations of the Holocaust on screen, surprised everyone by praising Son of Saul, calling it the “anti–Schindler’s List.” He specifically commended the film’s focus: rather than presuming to evoke the Holocaust as such, László Nemes concentrates on the experience of one man, a Hungarian Jew named Saul (Géza Röhrig), who is a member of the Sonderkommando in Auschwitz.

That focus indeed accounts for the power of this first feature by Nemes, a former assistant to Béla Tarr. The Sonderkommando, an opening caption explains, were prisoners dragooned into assisting with the daily business of execution. We see Saul looking on expressionlessly as new arrivals are ushered into the gas chambers; clearing away clothes even while their owners are being slaughtered; scrubbing the chamber floors afterward; dragging away the corpses. The work of the Sonderkommando was a form of complicity far beyond the merely untenable, and it did not even ensure its members’ survival: they were destined to be rapidly killed in their turn.

Son of Saul

In the course of his duties, Saul hears the breathing of someone who, extraordinarily, has survived the ordeal of gassing—an adolescent boy, who is then promptly asphyxiated by a German doctor. Seemingly recognizing the boy as his own son—although other prisoners later question whether he really has one—Saul resolves to find a rabbi to ensure proper burial of the boy. He pursues this obsessive quest at the expense of all else, even while other critical events go on around him: a plan to take photos that will expose the truth of the camps to the outside world, and an escape attempt. Saul participates in both schemes, but it’s as though they’re happening outside him, without his being fully conscious of taking part. His search for a rabbi, meanwhile, is one of those symbolically charged missions that can be read as either redemptive or futile. To take such an act seriously in fiction requires a leap of faith on the part of the viewer, and the film places Saul’s purpose in question, especially given its eventual outcome. What can such a mission possibly mean in Auschwitz, especially on the part of a man pressed into the service of murder?

Son of Saul is neither melodramatic nor mundanely centered on redemption, par excellence a theme devalued by cinema. Nemes’s film is, most immediately, about what we do and don’t see, what can and can’t be shown. Nemes elaborately stages a graphic, large-scale reconstruction of the workings of Auschwitz (crowds led into the gas chambers, piles of naked bodies, summary executions)—yet, by and large, obscures these sights. We know that atrocities are taking place, but for most of the time, they are kept out of focus in the background—while Saul, on whom the camera hangs almost continuously in the film’s extended takes, occupies the foreground, his head and shoulders literally blocking out what surrounds him.

Purchase the November/December issue to continue reading this feature.