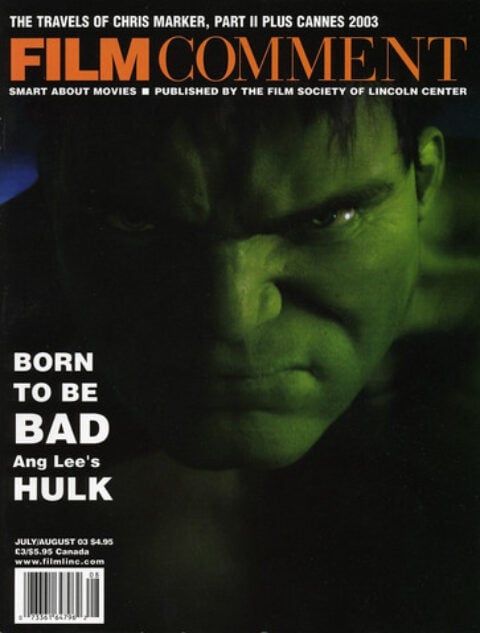

Something’s Gotta Give

The Incredible Hulk, as a comic book, was a model of narrative clarity. It had the bracing simplicity of garage rock, modified by a note of piercing melancholy that evoked Smokey Robinson’s “I’ve Got to Dance to Keep from Crying.” The Hulk himself, barreling through all snares and obstacles while uttering a few characteristic monosyllables (“Hulk trust no one!”), was the embodied spirit of comic books. But the flavor was in the sadness: when the Hulk wasn’t throwing his weight around against the likes of the Rhino or the Behemoth, he was lost in contemplation of a solitude beyond redemption.

Consider the end of a typical late-Sixties installment entitled, with a nod to James T. Farrell, “A World He Never Made.” The Hulk, after a whirlwind of cosmic adventures whose implications he has as usual only half understood, finds himself on a rocky cliff at night, standing between the abyss and the stars. Framed with spare eloquence by Marie Severin’s graphics, he launches into a soliloquy steeped in the Romantic sublime: “Can the Hulk never reach the stars? Or will I always be earthbound—Trapped in a world that hates me!—With no place to go—No one to turn to—Doomed to live in my own lonely prison—In the body of—The Hulk!!”

The Hulk as originally conceived was Frankenstein’s monster born from the body of Frankenstein himself. But the figure of the Faustian scientific experimenter had in the meantime undergone a mid-century American sea change into Dr. Bruce Banner, peerlessly brilliant physicist and quintessential 98-pound weakling, a nerd with thick-rimmed glasses and a heart devoid of malice up until the moment when he was caught by accident on the testing site of his newly invented gamma-ray superweapon. The monster into which Banner was transformed was no more malevolent than the physicist himself. The Hulk was a giant baby whose tantrums could level cities, an innocent guilty at worst of phenomenally poor impulse control.

Whatever violence he wrought was in response to the pressures the world put on him as punishment for the crime of merely existing, a crime for which Dr. Banner (by now a fugitive hunted by the U.S. Army raider the command of the harrumphing General Ross) was likewise condemned by association. “The sleep of reason breeds monsters”: Banner could not remember what he did as the Hulk, while the Hulk was only dimly aware of the brainy alter ego whose vulnerability he resented. The unending serial described a constant oscillation between intelligence without power and power without intelligence. The identity switch inevitably occurred at the worst possible moment. It was not so much a mythology as a permanent shuttling between two equally untenable situations: “No rest for Hulk!”

If Hulk, when announced, seemed the unlikeliest of projects, it is perhaps because Ang Lee’s reputation as a director characterizes him as something of a Bruce Banner, in a world where many of his colleagues might be likened, if not to General Ross, then to the Hulk’s most amusing superfoe, that high-domed petulant megalomaniac The Leader. Violence in Lee’s films has a way of being diffused, slowed down, as if destructive force could be averted or transformed if stared at with sufficiently calm attentiveness. In Crouching Tiger, Hidden Dragon, the bloodshed and bone-cracking martial arts films to which it pays homage is transmuted into a hypnotically alluring, almost disembodied battle of forms, where death seems more translation than destruction skirmishes. The Civil War skirmishes and guerrilla raids of the underrated Ride with the Devil acquired a suspended, wraith-like beauty in Lee’s gaze, as if his renegades could establish a buffer between death and themselves by sheer force of feeling. The freak electrocution death at the end of The Ice Storm retroactively galvanizes the whole film by manifesting so abruptly and decisively a destructive potential that has been muffled by layers of social evasion and deflection. Lee has been at home—whether in The Wedding Banquet or Sense and Sensibility—with those who will go to extraordinary lengths to prevent a harmonious social fabric from being ripped apart by unscheduled emotions.

Was Hulk a way for Lee to confront the clobbering or convulsive immediacy that his other films have in one way or another kept at bay? If so, the upshot can perhaps be regarded as a deliberate surface that measures the gathering of tension in his earlier films. This time around the apprehension of leakage, of spilling over, is underlined from the start with images of molecular swirl and animal experimentation. The instability lurking at the core of form itself nudges threateningly on every level, starting from the building blocks of organisms. A maimed starfish, an exploding frog: the Berkeley Nuclear Biotechnology Institute appears to be a digitalized theater of cruelty where the elements of life are punished into metamorphosis.

This descent into a chaos of morphology is mimicked by a barrage of computerized morphing. The screens that split and flip and overlap, as if to replicate the effect of a comic book page where all the frames occupy the field of vision simultaneously, altogether lack the Pop Art giddiness of Marvel Comics in their heyday. The effect is more of the unease that might result from having too many surveillance monitors running and never enough time to track what they’re revealing. The laboratory where Bruce Banner and his colleagues work at genetic engineering merges with the image-making process of which the film is both product and witness. Hulk suggests a residual discomfort with its own means; the image seems almost under attack, beset by a thousand tiny agents of fragmentation. We are far indeed from the liquefied spaciousness and cloudy ballets of Crouching Tiger. Here there is hardly time to focus on a composition before it is being messed with, intruded on, revised, subdivided.

You can read the entire article in the July/August 2003 issue.