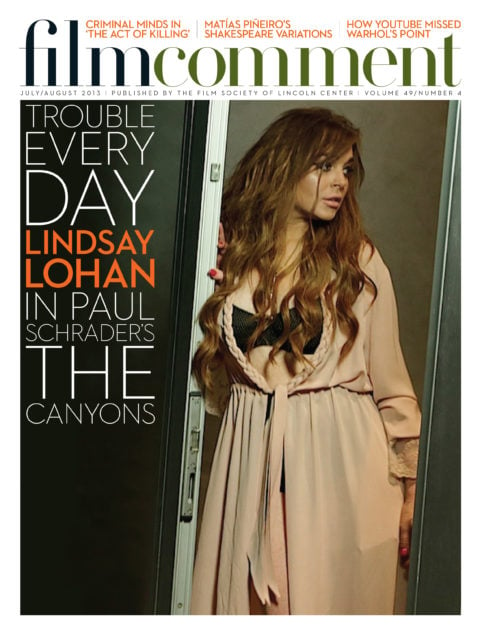

While preparing and directing The Canyons I was reading James Goode’s book The Making of the Misfits, and I was struck by the similarities between Marilyn Monroe and the actress I was working with, Lindsay Lohan. (I wasn’t the only one so struck. Stephen Rodrick, a writer for The New York Times Magazine who was on set with us, titled his article about the film “The Misfits,” which appeared on the cover with the line: “This is what happens when you cast Lindsay Lohan in your movie.” Not even the Times is immune to the hurricane force of the LiLo phenomenon.)

Similarities? Tardiness, unpredictability, tantrums, absences, neediness, psychodrama—yes, all that, but something more, that thing that keeps you watching someone on screen, that thing you can’t take your eyes off of, that magic, that mystery. That thing that made John Huston say, I wonder why I put myself through all this, then I go to dailies.

Monroe and Lohan exist in the space between actors and celebrities, people whose professional and personal performances are more or less indistinguishable. Entertainers understand the distinction. To be successful, a performer controls the balance between the professional and personal, that is, he or she makes it seem like the professional is personal. It is the lack of this control that gives performers like Monroe and Lohan (and others) their unique attraction. We sense that the actress is not performing, that we are watching life itself. We call them “troubled,” “tormented,” “train wrecks”—but we can’t turn away. We can’t stop watching. They get under our skin in a way that controlled performers can’t.

I think Lohan has more natural acting talent than Monroe did, but, like Monroe, her weakness is her inability to fake it. She feels she must be experiencing an emotion in order to play it. This leads to all sorts of emotional turmoil, not to mention on-set delays and melodrama. It also leads, when the gods smile, to movie magic. Monroe had the same affliction. They live large, both in life and on screen. This is an essential part of what draws viewers to them.

Lohan has outgrown her adolescent roles. All those cute all-American girls with the all-American names (Hallie Parker, Annie James, Anna Coleman, Cady Heron, Maggie Peyton), they’re gone. And in their place is another all-American type, the tough-talking, cigarette-smoking, streetwise girl, the blowsy blonde—Gena Rowlands, Ann-Margret, Shelley Winters, Angie Dickinson. Yet shining from within remains the little girl from the Disney films—a sweetness that makes the hard shell vibrate. Just like Marilyn.

But LL is not MM. The differences are even more interesting than the similarities. Those differences are marked by the almost 50 years that separate Monroe and Lohan. Over that time our notions of acting, stardom, celebrity, and talent have fundamentally changed. Marilyn had two things going for her that Lindsay doesn’t. She was the product of a culture that mandated public responsibility. An acting gift, good looks, and a zesty personality only got you so far. To be taken seriously one had to appear serious: study your craft, be mentored, read literature, respect your creative elders, marry a playwright, get the support of an established theater group or studio. To receive the system’s rewards—fame, money—you playacted by the system’s rules. And Monroe did.

Second, Monroe was a product of the studio system. The studios used their influence in the media and the courts to protect their stars. Damage was controlled and discipline en-forced. It’s inconceivable that Monroe would have faced the legal troubles that have beset Lohan over the last five years. A star’s difficulties only became public when they were impossible to contain; until then, he or she was protected.

Today’s situation is reversed: it’s possible to become a star without being taken seriously, to be a “media personality.” LL lives in a world of instant celebrity gratification Monroe could have only dreamed of. Paid for public appearances, paid to wear clothes, paid to pose, paid for gossip tips, paid for tweets. These rewards are available without the pretense of responsibility. On the other hand, there’s no system to protect today’s celebrities from the media or the courts or themselves. The same system that rewards irresponsibility punishes it, a punishment that is intensified by the vulgarity of discourse on the Internet.

It’s not a positive environment for the performer. It’s difficult to maintain self-discipline in a world of easy gratification. And it’s exhausting. As I said to Lindsay on a number of occasions, “It must be exhausting to be you.”

From a selfish point of view, from a director’s point of view, that is, from my point of view, it was a treat to work with Lindsay. All the drama, the mishegas, all the stress—that means little. A director can shoot around misbehavior. He can’t shoot around lack of charisma. I just wish it was easier for Lindsay.