Scare Tactics: House of Pain

Creating true crawl-under-the-seat, palm-piercing, cover-your-eyes tension is a rare, undervalued cinematic art. There’s certainly no shortage of filmmakers who give it a try, but only a select few would make Hitchcock proud. Just check out the current streaming sites, where you will find an endless barrage of unheard-of, undistributed, and/or unwatchable titles—the kind that frustratingly continue to give horror a bad name. (Critics somehow seem to forget that every genre has a pretty equivalent ratio of stinkers to gems; it’s inevitable that the sometimes hardcore content is off-putting to certain viewers—but, let’s face it, romantic comedies are some people’s horror movies.)

Though relatively new to the game, Fede Alvarez is already one of those select few, quickly proving himself a standout master of suspense. The Uruguayan writer-director, who was handpicked by Sam Raimi—for his first feature!—to helm the 2013 Evil Dead remake, initially attracted genre aficionados’ attention with a handful of shorts that clearly demonstrated his aptitude for playful yet intensely brutal filmmaking, as well as for his lean, mean storytelling—demonstrated most concisely by the total mass destruction caused by the giant robots that invade Montevideo in the under five minutes of 2009’s Panic Attack!.

Accepting the challenge of Evil Dead was in some ways an obvious choice—who could really say no to Raimi?—but it was also a bold move, in that it was a movie most horror fans did not want to see the light of day (myself included). But somehow it seems as if by dropping the introductory “The” of the universally adored original’s title, Alvarez was saying that he knew the definitive version had already been made, and that he was just going for it anyway, giving it all he had. And much to all the naysayers’ surprise, it did turn out to be an uncommon exception to the “remakes suck” rule, an immensely stylish and intensely gruesome film that grabs you from its jolting opening demon-burning sequence right through to its ultra-gory, sequel-promising conclusion.

Evil Dead

His newest, Don’t Breathe, also grabs audiences by the jugular from its first seconds, when we begin slowly zooming in from high in the sky as a man drags a woman by her hair down an empty rural street, leaving behind a thin trail of blood along the pavement. It’s a striking image, one that distracts you from thinking too hard about the nastiness taking place—or where it might fall in the narrative—because of the starkness and perfect framing of the shot. It’s an aesthetic that’s maintained throughout the film by the impeccable cinematography of fellow Uruguayan Pedro Luque (who also shot Panic Attack! for Alvarez as well as Gustavo Hernández’s notably one-take The Silent House and his stunning, yet-to-be-released follow-up Local God). It’s conflicting, perhaps, to portray violence with such striking precision, but it can’t be denied, and could even be what, in the right hands such as these, transforms a potentially gratuitous story into bona fide art.

As with his 2005 short, El cojonudo (yes, that’s Mr. Big Balls to English speakers), Alvarez’s protagonists in Don’t Breathe are motivated by money. In the short, it’s the main couple’s greedy quest to uncover hidden cash in a creepy house that brings about their bloody demise. And in Don’t Breathe, we are essentially rooting for three young petty criminals—a cute, edgy blonde girl (Jane Levy, dark-haired in Evil Dead), her tough-talking idiot boyfriend (Daniel Zovatto), and the more conscientious guy who quietly pines for her (Dylan Minnette)—who are just desperate to escape their dead-end lives in rundown Detroit. One of the many intriguing elements of the film is that it resides almost entirely in a moral gray area. Its “heroes” are crooks and their latest robbery victim—a man they know very little about, except that he’s blind, has a pit bull and most likely a few hundred thousand dollars locked in a safe somewhere—quickly becomes the “villain” when the no-nonsense Gulf War vet begins to aggressively fight back against his home invaders.

They are all, in fact, flawed human beings, trying to best play the bad hands life has dealt them. The trio comes from broken homes, abusive to varying degrees. And the unnamed blind recluse (brilliantly played by Stephen Lang, the acclaimed stage and film actor with a perfectly deep, menacing voice, perhaps best known for—and the best thing in—Avatar) lost his vision in combat action and, later on, his daughter in a terrible accident. The wall of his bedroom—where he falls asleep to old home movies of his child—features the faded outline of a once-mounted crucifix, for life’s hardships have stripped away his faith, and, as he says, man can do anything when he accepts that there is no God. If the robbers had actually known the lengths to which he was willing to go, and what takes place behind his heavily secured doors, they probably would have chosen another house.

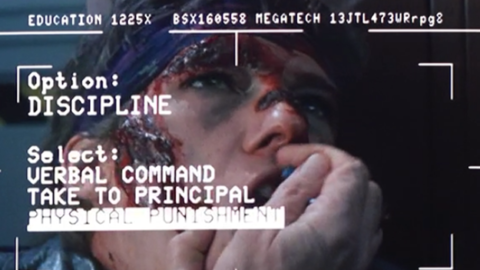

Don't Breathe

It’s the obsessive attention to detail like the cross as well as the impeccable sound design—hearing is of course a sense that is heightened for a sightless person—that help make the film stand out as being much more than an unrelenting exercise in suspense. Every tiny noise (creaking floorboards, vibrating phones) and facial expression (the film relies greatly on close-ups of eyes widened in terror) matters deeply. And perhaps most important of all is the terrific location. Don’t Breathe unfolds mostly within the drab interiors of the blind man’s dilapidated home, in a ghost neighborhood—he appears to be the only resident remaining on the block and probably many surrounding ones too—which of course means there’s no one around to hear anyone scream. On the first and second floors of the house, in which the intruders have been boarded in and left to their own devices for survival, they have the upper hand, but they’re the blind man’s equals in sight in the dark of the basement. And the cat-and-mouse games that take place there are some of the film’s most heart-pounding scenes—with another involving a turkey baster the most memorably revolting—rivaling only the thieves’ run-ins with the dog, who’s every bit as persistent as his owner.

People so often write off horror directors as hacks. In the past, beyond the consistent quality output of mainstays such as Romero and Carpenter, it would require the artier likes of Cronenberg, Polanski, and Kubrick to sidestep into the dark, dark side to get the most rigid of the highbrow to take notice, but so few modern masters dare to take the risk. That’s why filmmakers like Alvarez, Hernández, Dennis Iliadis, Jeremy Saulnier, and Adam Wingard, to name a few of today’s most dedicated and talented, are so vital. If they were making “honorable” films, they would most likely be earning widespread acclaim. Alvarez recently passed on helming a Marvel movie for lack of creative control. Luckily for us, he and the others have chosen—and will hopefully stay true to—horror. The genre needs them, and more movies of the caliber of Don’t Breathe.

Closer Look: Don’t Breathe opened on August 26.