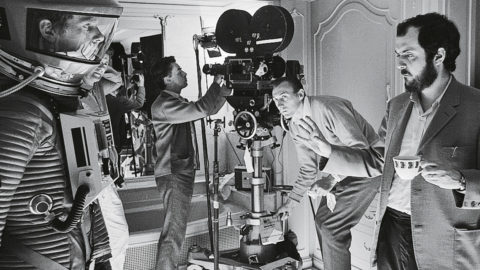

“I’ve never been able to decide whether the plot is just a way of keeping people’s attention while you do everything else, or whether the plot is really more important than anything else, perhaps communicating with us on an unconscious level which affects us in the way that myths once did.”

—Stanley Kubrick to Michel Ciment

In the years since Stanley Kubrick’s death, his films have come to seem ever more anomalous. Some of this has to do with his movies’ characteristic registers, which, in their mixture of grandiosity, the monumental, with intimations of a weirdly teasing, hermetic design, suggest nothing so much as an unholy Farberian crossbreed: the elephantine termite. Kubrick’s notions of performance are every bit as unusual as Bresson’s, though often split between extremes of a) an arch and airless banality that might be modeled on the speech of Sears mannequins after store hours, and b) isolated cartoon gargoyles who climb the curtains and chew on chairs. Formally, he’s often elegant but never really light, and it’s perhaps this trait, along with his penchant for broad and sometimes underlined effects, that accounts for Kubrick’s chilly reception among American auteurists—he looks lumbering next to Hawks or Walsh.

But whether that’s the proper company to place him in—if not them, then who?— remains a question that hangs there, and it’s linked to the larger issue raised in the quotation above, namely what “do[ing] everything else” meant to Kubrick. For all his carefully cultivated image as hyperrationalist chess-master to the muses, there’s a parallel sense that the films themselves are trying to push past the consciously thinkable and speakable to some area of unconscious transmission. In interviews, he often expressed nostalgia for the economy of silent-film narration, a pictographic language where words serve merely as a denotative frame. 2001: A Space Odyssey is certainly the turning point in his career, and that film gives us an example of this pure image language early on, when inserts of the mystery slab and a felled tapir spark the notion of tool (and weapon and murder) in the cloudy mind of the idling ape-man. It sometimes seems as if this film, and this scene in particular, announce the course Kubrick would doggedly follow in much of his later work, that these imposing, polished, opaque movies aspire to the condition of the monolith.

Another way to frame the Kubrick conundrum is to ask, what type of eye are we seeing through? It’s the central question of what may be Kubrick’s most self-reflexive film, The Shining. From its opening shot—a glide across a mirror lake that skews and tilts mid-path as if to indicate that this is no neutral, establishing eye but one imbued with agency—the movie is a veritable encyclopedia of point-of-view strategies. The basic, classical point-of-view sequence is built on a boomerang curve between person looking and thing seen. Horror films and thrillers have gotten a lot of mileage out of selective use of “displaced POV,” where individual shots are marked as subjective but the seeing face is withheld, often until the climax. Kubrick never grounds his overlooking eye at all, preferring instead to play through seemingly every variation on displaced, deceptive, and impossible POVs. Not the least of these centers on the telepathic communications of “shining” itself, another vehicle for the pictographs of “pure cinema.”

All of this reaches some apogee of complexity in the Room 237 sequence, in which POVs are nested like Russian dolls. Danny, in psychic communication with Dick Halloran, the hotel’s distant cook, “shines” into his father’s vision as the latter enters the room, but this is at first only indicated by the camera’s height. As Jack steps into the bathroom, we’re granted a reverse angle, and a softcore parody of the Kuleshov experiment, as Nicholson spies a naked woman and telegraphs the stages of his shaggy desire. Following their kiss, and the woman’s transformation into a rotting corpse, the movie goes briefly into POV freefall, as it cuts quickly between Jack’s vision as he retreats backwards, a reverse angle that seems to belong to the corpse, Danny transmitting all of this, Halloran receiving it, and a few quick shots of the corpse rising from the bathtub that can’t be definitively tied to any of them. These bathtub inserts could be Danny’s memory, or Halloran’s, or the hotel’s intrusion on the psychic partyline, or Jack eavesdropping on any one of these, since he seems to develop the capacity for some darker shining over the course of the film. There’s finally no way to parse all of the elements of Danny’s communication. And yet something has been transmitted.

“History is a nightmare from which I am trying to awake.”

—Stephen Dedalus, Ulysses

“Danny can’t wake up, Mrs. Torrance.”

—Tony, The Shining

Rodney Ascher’s documentary tells a number of tales of Shining obsession, but behind all of them is the story of the technological shifts that gave rise to such attentions, specifically the way viewers’ relations to movies changed when they became ownable objects. At this point, it’s become hard to conjure a living notion of a time when it was otherwise, when years could pass between opportunities to view a favorite film, and it’s likewise hard to remember or imagine what it must have felt like to suddenly be able to hold one in your hand, contained in something near the size of a paperback.

The Shining seems engineered for these new modes of viewing, the abilities to pause, to slow, to rewind and perpetually rewatch. 2001 ropes off discrete zones for its mysteries, but The Shining has more nooks and hiding holes. The film’s magnetic hold on some viewers (reader, I was one) is in large part due to the lure of the Overlook itself. How familiar, how mappable, it comes to look over the course of those long tours and trike rides. The film seems to offer continual teasing hints that all the answers are there if we could only see more clearly, move closer, finally enter in. And through DVD to Blu-ray, each evolution in technology renews the invitation.

Ascher’s subjects scrutinize the film with the zeal of medieval kabbalists, never knowing which prop or wall hanging might hold the key to the whole. Each of them posits one or more covert narratives running behind the scenes: the slaughter of the American Indians (a theme in the film Fredric Jameson had already identified in the early Eighties); Kubrick’s attempt to come to grips with the enormity of the Holocaust; his confession of a Faustian pact with the U.S. government, to create faked moon-landing footage; a reworking of the myth of Theseus and the Minotaur. Every object in the film comes to seem hyperlinked to an entire explanatory apparatus, and to the Overlook itself, like some Pynchonian repository for all the hidden histories, both the horribly real and those that lie in the zone of myth and shadow. It may even be in this very profusion that The Shining comes closest to revealing itself.

There’s a notion of art behind some of the interpretations in Ascher’s film that isn’t unique to America but certainly flourishes here—that of the achieved artwork as a gigantic rebus or cryptogram, with the artist some quasi-divine puzzlemaster in the wings. It’s a mode of approach that has proven to be well matched to the scattered intensities of the Internet, and creative readings proliferate there. But many of these Net exegetes seem loath to describe their activities as creative, preferring instead to present themselves as detectives on the case, or high priests of the mysteries. The notion that a viewer can enter into a collaborative engagement with a movie runs strongly counter to this attitude, in which intention is everything and everything is intended. Such a yearning for closed works and utterly controlled spaces finds a happy home in the Overlook. The Shining is forever reflecting its most single-minded interpreters back on themselves.

You can probably go a little crazy if you look too long at anything, and the winding, shifting halls of the Overlook are especially easy to get lost in. In fact, as Juli Kearns, one of Ascher’s subjects, found, when you try to slot the spaces together they collapse into incoherence. Another interviewee, John Fell Ryan, may have devised the perfect emblem for Shining obsession by organizing screenings where the movie unfurls on top of itself, simultaneously projected forward and backward in superimposition. Shown thus, it becomes a snake devouring its tail, and perhaps at its central crossing lies Jack’s pile of dead yellow pages with their endless variations on a single sentence. Ryan admits that the film may be an elaborate trap but suggests that Danny’s evasive maneuvers in the hedge maze offer an exit strategy: stepping backwards in your tracks, leaping to the side, and tracing the trail back to the entrance.