Siskel and Ebert and Disney.

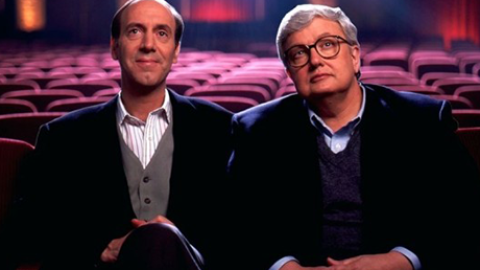

Richard Corliss is generally correct in his discussion of new developments in popular film criticism (FILM COMMENT, March/April 1990). The age of the packaged instant review is here, and lots of moviegoers don’t have time to read the good, serious critics—the Kaels and Kauffmanns. Thumbs, star ratings, grades, and the marvelous Franklin scale have made it unpopular, if not impossible, for critics to deliver an ambiguous or uncertain opinion of a movie (quick: Last Year at Marienbad—thumbs up or down?). Newspaper editors around the country want colorful capsule verdicts on the new movies for their weekend pull-out sections, and the TV stations in most major markets have local personalities who narrate clips from the new releases.

What Corliss does not realize is that this is an improvement, not a deterioration, of the situation as we both found it in the mid-Sixties when we started in the business of writing about films. That was a time when there was no regular film criticism on national or local TV. Film magazines did not appear on the newsstands; although Film Quarterly and FILM COMMENT were being published, few outside academia and the film industry knew about them. Variety was the showbiz bible, with the emphasis on biz. As a matter of policy, most daily newspapers did not publish film reviews. In general-circulation magazines, the great influential voice in the late Fifties and early Sixties belonged to Dwight Macdonald, in Esquire, the man who taught me that movies were to be taken seriously.

The single most influential event in the history of modern newspaper film reviewing took place as recently as 1963, when 20th Century-Fox banned Judith Crist from its screenings after she attacked Cleopatra in the New York Herald-Tribune. This development so tickled the public fancy that it became necessary for the trendier papers to import or create their own hard-to-please reviewers.

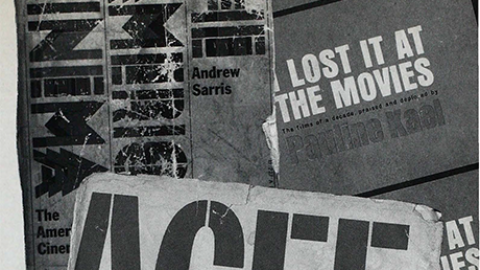

Before 1963, with the exception of a handful of papers in New York, Los Angeles, Washington, and a few other cities, newspaper film criticism existed on a fan-magazine level, if at all. Most movie reviews were ghosted by various staff writers under a house byline (Mae Tinee—get it?—in the Chicago Tribune). But by the middle years of the decade, any self-respecting paper had its own local critic, and everyone of them had studied Kael’s I Lost It at the Movies and Andrew Sarris’ The American Cinema.

That was a good time for the movies, as who needs to be reminded. Something called the “Film Generation” made a newsweekly cover, and films like The Graduate, Blow-Up, Weekend, Bonnie and Clyde, Persona, and 2001 were opening. Revival theaters flourished in the larger cities. Film societies did standing-room business on every campus. Harvard students knew Bogart’s dialogue by heart, and in Chicago the Second City nightclub cleared its stage on Monday nights for screenings of underground films.

All that was long, long ago. It is probably true that today’s average, intelligent, well-informed American undergraduate has never heard of Luis Buñuel, Jean Renoir, or Satyajit Ray, and if you find one who identifies Hitchcock, Truffaut, Kurosawa, or Bergman, hang on to him—he’s got the fever.

The death of the repertory and revival houses in most cities has been duly mourned, but who is there to grieve the death of college film societies, which have shut down on one campus after another? Douglas Lemza of Films Incorporated, the largest 16mm film rental company, tells me that classic and foreign film exhibition on the campus is dying or dead, replaced by videocassettes on big-screen TV. The auditoriums where once we saw Ikiru are silent now on Sunday nights, but down in the dorm lounge the kids are sitting in front of the 50-inch Mitsubishi watching Weekend at Bernie’s.

The most depressing statistic I know about patterns in U.S. film exhibition comes from Dan Talbot, veteran head of New Yorker Films. He says that an average subtitled film will take 85 percent of its box-office gross out of theaters in only eight North American cities, and will never play at all in most of the others. Vast chains like Cineplex Odeon have gobbled up the smaller local and regional exhibitors. Chicago’s Biograph, which used to be an arthouse, was playing a Steven Seagal thriller the last time one drove past; the Cinema Studio, home of subtitled films, is the latest Manhattan art theater to close. In the late Fifties, more than 40 college towns had theaters booked by the Art Theater Guild. Such a chain is unthinkable today. The growth of the Landmark chain of revival theaters in the Seventies was brought to an end by videocassettes. The bottom line is that mass-produced Hollywood entertainments dominate U.S. movie exhibition, and most moviegoers seem to like it that way.

In the days of my youth, the film societies and arthouses provided the environment where a serious film community flourished. People stood in line together, sat in the theater together, and hung out afterwards to talk about the best new movies.

Places where that kind of gathering can take place no longer exist in most cities. A few revival houses survive, and the largest cities have film programs at the art museums, or in subsidized cultural centers. There are more film festivals than ever. Every city worth its salt has one, and festivals like Telluride, Park City, and Mill Valley specialize in showcasing independent films. Even so, a young person seriously interested in film has little sense, these days, that he is part of a community. The collapse of campus film societies is the single most obvious reason for this. Serious discussion of good movies is no longer part of most students’ undergraduate experience.

Yet what about film criticism in these dark ages? It is thriving. There is more of it than ever before. Corliss can be forgiven, I think, for the elegiac tone of his farewell article; he is saying goodbye to FILM COMMENT after many productive and valuable years, and his leavetaking must be painful because a large portion of his life was invested in the magazine. But at least part of his discontent is a textbook case of mid-career crisis. He started with grand ambitions, he has achieved most of what he hoped for, and now he asks, with Peggy Lee: Is that all there is? Like many others his age (which is more or less my age), he finds the cause of his malaise in the disintegration of everything in general and other people’s standards in particular.

What strikes me as slightly disingenuous is his lament for serious film criticism. Here is a critic who did important work for the late New Times, who writes in FILM COMMENT as a sane, acerbic stylist, but who has chosen for himself the space and style restraints of Time where the best way for a writer to get more space is to sell the editors on a cover story about a star, then try to sneak criticism into the crevices of a personality profile. He praises our program Siskel & Ebert with faint damns (we are the best of a bad lot, I am a jolly chap, etc.) and then says, “I simply don’t want people to think that what they have to do on TV is what I’m supposed to do in print:’ But that is not the real problem facing Corliss, who might better have asked why what he has to do in Time is what he’s supposed to do in print. This is particularly sad because, with this farewell article, Corliss’ distinctive critical voice may actually disappear from view: That isn’t his own voice in Time, but a compromise with the magazine’s patois. To put it another way, his manifesto would read more convincingly if he were leaving Time to join FILM COMMENT. Corliss’ apocalyptic vision notwithstanding, good film criticism is commonplace these days. FILM COMMENT itself is healthier and more widely distributed than ever. Film Quarterly is, too; it even recently abandoned aeons of tradition to increase its page size. And then look at Cineaste and American Film and the specialist fan magazines (you may not read Fangoria, but if you did you would be amazed at the erudition its writers bring to the horror and special-effects genre). At the top of the circulation pyramid is the glossy Premiere, rich with ads and filled with knowledgeable articles that are not all just puff pieces about the stars—although some are. It is Corliss’ opinion that good film books are no longer published, but has he read David Bordwell on Ozu, Patrick McGilligan on Altman, or Linda Williams on pornography? Kael, our paradigm, continues at The New Yorker. Kauffmann gets more sense into less space than any other critic alive, at the New Republic. Denby is at New York, Rosenbaum at the Chicago Reader, Hoberman at The Village Voice, Mark Crispin Miller just had a cover story in the Atlantic, and on and on. The weekly Reader in Chicago, born in 1969, has spawned a new kind of national newspaper, the giveaway lifestyle weekly, and each of these papers—The Phoenix, LA Weekly, etc. has its own resident auteurist or deconstructionist. Daily newspaper film criticism at the national level is better and deeper than it was in Corliss’ golden age. Corliss mentions the invaluable Dave Kehr of the Chicago Tribune. Has he read Michael Sragow in San Francisco, Sheila Benson and Peter Rainer in Los Angeles, Jay Scott in Toronto, Howie Movshovitz and Bob Dennerstein in Denver, Jay Carr in Boston, Jeff Millar in Houston, Philip Wuntch in Dallas? And what about the college newspapers, where the explosion in film education over the past 20 years has generated dozens of undergraduate critics who already know more than some of their elders will ever learn? Yes, they are writing “Journalism” for the most part, and, yes, their reviews will yellow with age as those of Corliss’ fondly remembered Cecelia Ager did. But then they are journalists. It is not dishonorable to write for a daily deadline. No art form is covered more completely and at greater length in today’s newspapers than the movies. A lot of papers review virtually every film released—and, in many cases, no books at all (even The New York Times feels that one book review is sufficient on a daily basis). All this film criticism has not resulted in a more selective North American moviegoing public, nor has it created larger audiences for foreign or independent films or documentaries. It exists in a time when alternative films, theaters, and audiences are in disrepair.

But what of movie criticism on TV? Is it the culprit? What about Siskel & Ebert? I am the first to agree with Corliss that the program is not in-depth film criticism, as indeed how could it be, given our time constraints.* But Corliss has not bothered to really engage the program, to look at it closely and say what he thinks is wrong. He disapproves of the idea of Siskel & Ebert, but leaves it at that. (I wonder if Corliss watches the show very much—he gets the title wrong in his article and cites not a single moment from any segment. He would be incapable of writing a movie review as unfocused as his dyspepsia about S&E.)

The weekly program takes two basic forms—the review shows and the “theme” shows. The review shows are indeed as formatted as Corliss reports; typically, each involves reviews of five movies, with an ad-lib discussion after the written portion of each review, and then a summary featuring the infamous thumbs. Although Corliss thinks he has heard us telling jokes, in fact we have a house rule against any deliberate or scripted jokes—especially puns on names. Nor are our reviews limited to Corliss’ “five Ws— warm, winning, wise, wacky, wonderful.” In fact, his invention of this witty formula shows him using the very sort of jokey criticism he accuses us of practicing, although I will not deny the formula applies to many TV-based critics. Gene Siskel and I have an advantage over many other critics on the tube: we both still write for newspapers, where we have spent most of our time for more than 20 years. Most TV-based critics have never written a movie review longer than eight sentences.

I wish we had more time on the program. It would be fun to do an open-ended show with a bunch of people sitting around talking about movies—but we would have to do it for our own amusement because nobody would play it on television. The program’s purpose is to provide exactly what Corliss says it provides: information on what’s new at the movies, who’s in it, and whether the critics think it’s any good or not. Our show reaches audiences in nearly 200 cities. A typical letter from one of the smaller markets says, “None of these movies ever play within 50 miles of here, so thanks to your show at least we know what we’re missing.” In the golden age of the late Sixties, no film commentary of any sort reached most of the households in most of these markets (although faculty members on the local campus knew who Kael was, and huddled over the glow from their 16mm projectors like monks in the Dark Ages treasuring manuscripts from far lands). When we review a film that is not being released simultaneously on Siskel & Ebert’s 1,600 screens, our review is the only local exposure th at film receives in many cities. When we have an opinion about a movie, that opinion may light a bulb above the head of an ambitious youth who then understands that people can make up their own minds about the movies. And when we try to explain why Do the Right Thing is a better film than Driving Miss Daisy, although admittedly less enjoyable, it is a message not previously heard in many quarters.

This is not deep criticism—it is informed and sincere opinion. We do it better now than we used to, and we are still trying to get it right.

There is another thing we do on the Siskel and Ebert show that I am more proud of, and that Corliss does not mention. Over the past several years, we have had many “theme shows” exploring a single subject or issue. As a national program, we have been influential on some of these issues.

• When we devoted 30 minutes to an attack on colorization in October 1986, we were the first national TV program to mention the subject, and for a year we were the only one. We have renewed the attack several times.

• We were the first program to illustrate the virtues of letterboxing (March 1987 and subsequently), contrasting it to the butchery of cropping and pan-and-scan. The TV medium was ideal for illustrating specific examples, such as the disappearance of Mrs. Robinson in her key scene with Benjamin.

• We devoted a show to Spike Lee in August 1989, while Do the Right Thing was still in theaters.

• We did an entire program in celebration of black-and-white cinematography in May 1989, and filmed the show itself in black and white. It was the first new syndicated program shot in black and white in 25 years.

• We were the first program to feature laserdisks (May 1987) and demonstrate their features, such as simultaneous commentary on a parallel soundtrack.

• We attacked product placement-the insertion of incidental advertising in motion pictures—with shots of the stars seen clutching their Cokes and sitting behind their Dunkin’ Donuts boxes.

• In March 1987 we did a show explaining how the MPAA rating system was de facto censorship; we called for a new “R” rating for worthy films intended for adults, since the X rating dooms a film to automatic exclusion from mainstream distribution and exhibition channels. (The MPAAs March refusal to grant an R to The Cook, the Thief, His Wife and Her Lover is the latest example of the way a film can suffer in distribution. Many theater chains have contracts with their landlords prohibiting them from playing X-rated or unrated films.)

Siskel & Ebert was the first, and often the only, television show of any kind to deal with many of these subjects. It would be fair to say that most mainstream Americans who have formed an opinion on colorization and letterboxing were inspired to do so because of our program. (Video retailers say the Siskel & Ebert program on letterboxing caused a noticeable swing in the opinions of their customers on the subject.)

Corliss regrets TV’s lost opportunities for doing a “shot by shot” analysis of films. I do, too. I continue to use the shot-by-shot approach for the close visual analysis of films at least five or six times a year, on campuses or at film festivals. This is partly to keep in training, which is also the reason I teach a film class; a mind that considers movies only at review length will atrophy. Laserdisks make shot-by-shot analysis infinitely easier than the old stop-action 16mm projectors did; Donald Richie and I made our way a shot at a time through the Criterion disk of Ozu’s Floating Reeds last December at the Hawaii International Film Festival, and every frame seemed to reveal a new visual treasure. I would like to go through an entire film a shot at a time on television—or, more to the point, I would like to see a Scorsese or a Jarmusch go through one of his own films that way. Corliss and I both know this is not likely to happen. (There is, however, the happy alternative of laserdisks with running commentary on the soundtrack.)**

Progress comes slowly. We no longer work with Spot the Wonder Dog, for example, and I for one was able to contain my grief when the little beast died of kidney failure. We no longer waste a segment on the week’s worst movie—there are too many interesting movies to review. But I would like it if we took a scene by an interesting director and went through it with a voiceover analysis. And I would like it if we reviewed more independent and foreign films.

If there is a malaise eating away at the heart of film journalism these days, I submit it should not be blamed on the reviewers who work on television, We are addressing a different audience from the passionate elite who followed the Kael-Sarris Wars of the Sixties. Some of the critics on TV address them better than others, and all of us operate under Sturgeon’s Law (“90 percent of everything is crap”). There is room for improvement. Give me the opportunity and an audience that will watch, and I know where and how some of those improvements could be made. So do a lot of other people, but the daily reality of national television is unforgiving and not very flexible, and PBS provides even less leeway than commercial syndication. Yet we are not the Evil Empire of film criticism.

I submit to Richard Corliss that he missed the real source of distemper in today’s American film market, and that is the ascendency of the marketing campaign, and the use of stars as bait to orchestrate such campaigns. Reviewers, after all, can only offer their opinions on a new movie. Some like it, some don’t; together they do not have the impact of a well-coordinated national campaign that lands a popular star simultaneously on the covers of a People-type magazine, a newsweekly, several glossy monthlies, and the talkshows. Hollywood has never been more star-driven than it is at this moment, and publishers and producers have never been more eager to get their piece of the star of the week.

Isn’t it obvious that the auteur period is over with now—that we have passed through the age of the director, and returned to the age of the powerful studio and the star system? The most creative directors in America today mostly came from the Seventies; nobody since Scorsese has been better. For every Eighties director with a style and something to say—for those like Gus Van Sant Jr., Spike Lee, and Jim Jarmusch—there are countless film-school technicians who know how to manufacture glossy generic entertainments and would have been right at home on the B-picture assembly lines of the Forties. (The difference is, in the Forties visual style was still prized; now most new directors depend on art directors for their visual impact, and give only perfunctory thought to camera style.)

In the Seventies we went to see the new Altman, Coppola, Fassbinder, or Mazursky film; the contemporary mass audience goes to see a star, special effects, or a high concept. Martin Scorsese says the monster hit—the $200 million-plus movie—is a new genre, and he’s right. The studios lob the blockbusters into the choice summer weekends, and lesser movies scatter out of the way. Today’s average moviegoers follow the works of Tom Hanks and Michelle Pfeiffer; they cannot identify many directors, and hardly care. Stars are seen as the auteurs of their films and why not, since what difference does it make who directed the next Schwarzenegger film when Arnold has the final authority?

Most big movies these days are packaged by agencies, who like to see their directors, writers, and actors working together. The director who has, God forbid, a personal vision to express will have to recruit support from an important star in the same stable to get his vision out the agency doors and into production. Actors who regularly work at scale or discount for directors they believe in—actors like Matt Dillon, Jane Fonda, Morgan Freeman, Gerard Depardieu, Genevieve Bujold, William Hurt, Peter Coyote—are in effect subsidizing what’s left of the auteur film.

In the meantime, popular film journalism has become starstruck with a vengeance. Not since the glory days of the glossy movie fan mags have stars been viewed so uncritically, so fawningly. Where did it start, this rhetorical hyperbole that attempts to transform the star of the moment into something more than human? I was among the many admirers of Emily Lloyd’s work in Wish You Were Here, but after reading some of the profiles I wondered how I had failed to properly appreciate her translucent skin, her sparkling eyes, her grace, her effervescence, her brilliance. We should fall on our knees in gratitude that she walks among us. Then Emily Lloyd went on to create more difficult performances (flawlessly using American accents unfamiliar to her) in two box-office flops, Cookie and In Country, and where were her idolaters? Lighting candies before Laura San Giacomo and Julia Roberts.

There’s nothing wrong with expressing enthusiasm for movie stars, but there is something wrong with the media lining up and volunteering to be part of the hype. In the closing weeks of 1989, the hottest new movie was Born on the Fourth of July and its star, Tom Cruise, was the most desirable magazine-cover subject in America. According to reports published a few months later, Cruise had promised his friend, Rolling Stone publisher Jann Wenner, an exclusive national magazine cover. But when Born on the Fourth of July turned out to be a powerful and controversial picture, his promise seemed unwise. Time magazine, for example, wanted Cruise. And so, according to the reports, Cruise asked Wenner for a favor: could he be released from his promise, so he could be on the cover of Time? And Wenner, aware that this could help his friend’s chances of an Academy Award nomination, assented. Cruise’s publicists then agreed to give him to Time—and not, for example, to Newsweek.

Do you see what’s wrong with this picture? Any hardboiled old-time newspaperman could tell you. A publicist should not be able to give a newsweekly “permission” to run Tom Cruise on its cover. Time magazine should run whom it damn well pleases on its cover-as it used to do. And if Newsweek wanted to run Cruise the same week, it should have. The key, of course, is that the favored magazine is being offered two carrots: exclusivity, and access to the star for an interview and photo session. It is never spelled out that the magazine’s critics will subsequently give the movie in question a favorable review, but any reasonable publicist would assume that a magazine would not want to feature someone who was in a bad movie.

Here is the definition of an “exclusive interview” with a star: he will say the same things he always says, but for a two-week window he will say them only to you (and to one, but only one, of the morning TV talk shows). Usually this means the writer has his work cut out, since the editorial space available for a cover profile far exceeds what can intelligently be written on the subject, unless the star can be pumped up into a trend or a demigod. (The really interesting talkers—Teri Garr, Harry Dean Stanton, Albert Brooks—are not usually cover material.) In a process possibly designed to silence his own doubts about the newsworthiness of his subject, the writer then inflates the star-of-the-week with prose that approaches hagiography.*** The superlatives used in Time to describe Tom Cruise would have seemed embarrassingly inflated if applied to a philosopher, poet, religious leader, or statesman. Whatever happened to the Time that used to be known for its sneaky puns and wise-guy cynicism? When did it join the packaging team?

Stars are marketed to local TV and newspapers in the same way. Lest anyone think I am singling out the newsweeklies, I hasten to confess that my own editors sometimes treat their entertainment writers as a journalistic version of the old Frank Buck radio program, Bring ‘Em Back Alive. No Sunday paper is complete without an endless “celebrity profile” (papers like The New York Times, where the critics do “think pieces” on Sundays and never interview anybody, are rare indeed). First the star sells the medium, and then the medium sells the star and his movie. Around and around.

There is little room in this circle for a movie without a star. That is why Hollywood stars are worth the salaries they are getting, and why some stars now make as much as a movie used to cost. Once upon a time, new releases opened in New York and rolled out across the country. Now they open everywhere on the same day, and in the seven days before they open you can see their stars on magazine covers in every checkout line, and hear them talking on every interview show-backed up, of course, by TV spot commercials.

Then, on the Monday after opening, the box score appears in USA Today. We learn the “box-office winners” of the previous weekend, and the “per-screen average” of the leading contenders. USA Today was the first to turn trade information into a national scoreboard, but now the totals are carried by the wire services and faithfully announced by disk jockeys. Corliss is disturbed that potential moviegoers only ask “What’s it about?” and “Who’s in it?” He should examine his feelings the first time he is asked about a film’s per-screen average.

Do people still read and care about serious film criticism? That is the real question in the Corliss piece, and I think the answer is, yes, they do—the same people who always did, and probably a few more. To which we can add the greatly in creased numbers of people who read and care about serious film journalism, as provided in Premiere and many other magazines and local newspapers. Are the movie critics on TV preempting the audience for such writing? No. They serve a different function, for a different audience, and in an age when celebrity puff-pieces are a sponge soaking up the available media time and space, at least they offer critical opinions, not fan letters.

Why are the movies not as exciting as they used to be, and why are there fewer unconventional ones, and why is there no audience for repertory and campus film societies? Because (1) home video is killing 16mm exhibition and all the film communities and programming that revolved around it, and (2) modern marketing techniques have consolidated exhibition patterns, so that movies can be block-booked onto thousand s of screens at once and sold in a media blitz.

Let’s face it. The sad fact is that film criticism, serious or popular, good or bad, printed or on TV, has precious little power in the face of a national publicity juggernaut for a clever mass-market entertainment. The marketing of stars has become synonymous with the marketing of movies. Stars have become the brand names of the industry. Bring ’em back alive.

* Corliss might be surprised to discover that he is not always right when he assumes his magazine reviews are longer than the S&E treatment of a film. On Blaze, the Time word count is 324, S&E 755. On Blue Steel, it was Time 267 words, S&E 864. In reviews of The Cook, The Thief, His Wife and Her Lover and Henry: Portrait of a Serial Killer, which both Time and S&E paired, the count was Time 660 words, S&E 1,589. On The ‘burbs, Time nudges us 603 to 471, and on House Party, 567 to 536, although, as Corliss points out, in addition to the words we also show clips from the films.

** The most detailed film criticism I’ve seen on American TV was The Men Who Made the Movies, the Richard Schickel PBS series where he led great directors through discussions of their themes and styles, then showed what they were talking about.

*** Corliss on Cruise: “The souped-up Chevy Lumina circles the track at North Carolina’s Charlotte Motor Speedway. At the wheel is Tom Cruise, daredevil superstar. The hazel eyes that laser out of his handsome face focus on the thrill of speed and risk. Nor is this challenge confined to a roadway’s hard curve; it applies as well to his career in the movies, even if it means taking dangerous curves toward roles that might confound his fans. This day, after a dozen laps, Cruise sees a dime, stops on it and emerges from the Lumina to say hello to a visitor. He extends a hand and flashes the million-dollar smile—or, to judge from the worldwide take of his past four movies, the $1.035 billion smile. He points to the car and asks, ‘Want to go around?’ America wants to go around with Tom Terrific—that’s how he looks, that’s how he makes moviegoers feel.”