Rise Up!

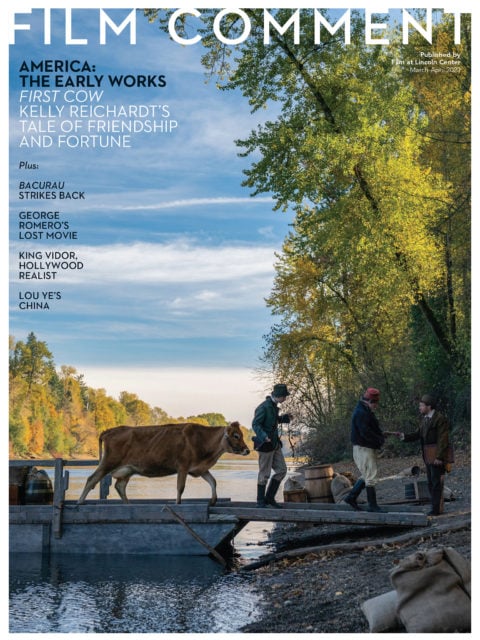

In Bacurau, a remote, isolated town is attacked by a small group of armed, drone-assisted outsiders. The sertão, or backcountry, where the action unfolds, has often featured in Brazil’s popular culture and arts as a forbidding, uncharted, and parched territory. It is the country’s Wild West—a vast landscape marked by violent conquest and the resistance of the indigenous people and the black quilombos (communities historically created by runaway slaves).

Kleber Mendonça Filho and Juliano Dornelles’s new film won the Jury Prize last year at Cannes, where it gave me one of my two most hair-raising moments during the festival’s screenings. Each happened when the social drama—in all its relatively recognizable, containable parameters—metamorphosed into fearsome, all-out genre action. One instance occurred in Bong Joon Ho’s juggernaut Parasite, when the struggling poor family assaults those even less fortunate. The other came in Bacurau, when the people of the convivial, quasi-utopian town—where tolerance and free love rule, and the goodly townsfolk gather to commemorate their deceased black matriarch, Carmelita—suddenly find out that they’re under attack. Immediately they dust off their cache of guns, and as they mercilessly defend themselves, carnage erupts.

One might call the sequence a carnival of blood, as the spectacle staged by Mendonça and Dornelles feels so highly performative, enhanced by the use of widescreen. Like Bong, the filmmaking duo presents us with protagonists whose humbleness in no way signals the ferociousness of their counterattack. But once horror is unleashed and Bacurau gears up, from complex exposé to full-throttled bloodlust western, it sure felt as if the images were shocking my nervous system. Yet equally rapid, almost uncannily so, is the villagers’ will to move on. Bacurau is a place that’s marked by violence, and yet its core ethos remains: to live and let live.

Who are these warriors of Bacurau? Among the town’s memorable characters is Domingas (Sonia Braga), the brazen local surgeon and reckless drunk and bigmouth—a remarkable role for Braga, whose past performances have often traded on sensuality, but who this time is more shrew than muse. Though much more temperate, Domingas’s soul sister is Carmelita’s granddaughter Teresa (Bárbara Colen, who played the younger version of Braga’s protagonist, Clara, in Mendonça’s second feature, 2016’s Aquarius). Her fortuitous return from the city is mirrored by a similar regress made by her occasional lover, Acácio (previously known as Pacote, a deadly contract killer)—a detail that suggests that the town has an eternal hold on all of its inhabitants. Acácio is just one of many characters who prove as striking as they are elusive—the same could be said about the outlandish yet intensely likable queer bandit, Lunga (Silvero Pereira). All, however, are quickly absorbed into the communal hive of Bacurau. Like the capoeira dance, Bacurau’s logic, its very pulse, revolves around collective action, on and off the battlefield.

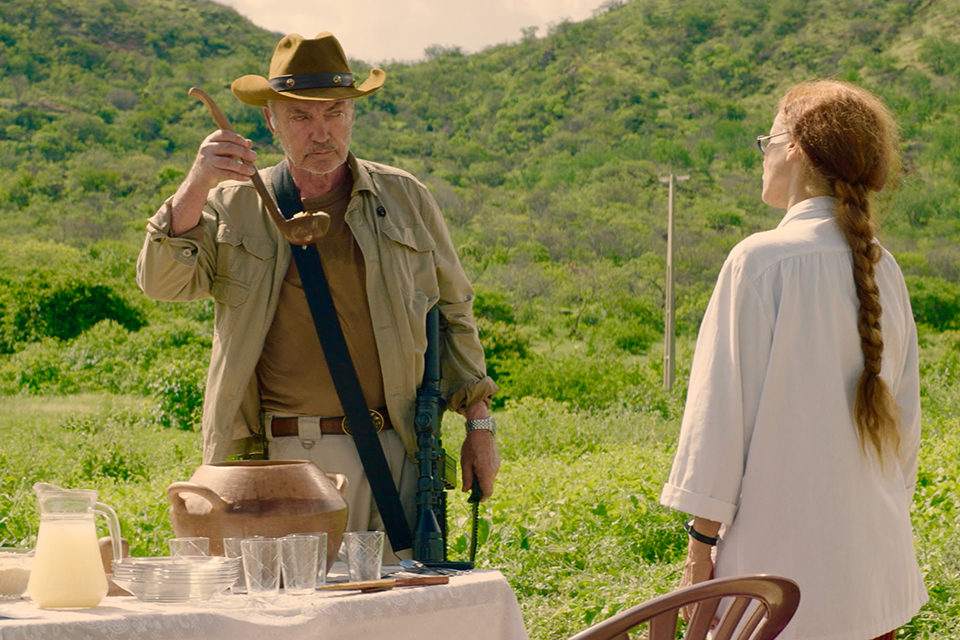

All photos by Victor Jucá. Courtesy of Cinemascópio Produções/Kino Lorber.

In its historical reckoning, Bacurau shares some DNA with Cinema Novo and with Luis Ospina and Carlos Mayolo’s “poverty porn” manifesto that, along with Glauber Rocha’s earlier aesthetics of hunger, has shaped critical discourse on Latin American cinema for the past few decades. Thematically, Bacurau is a corrective to certain ethnographic films that, up to the recent past, have too often framed non-western subjects as passive or “simple.” But stylistically, it’s closest to Ospina’s Pure Blood (1982)—an evisceration of the contemporary colonial mindset that, like Bacurau, pays a delicious, backhanded homage to Hollywood.

In a nice reflexive touch, the town of Bacurau has its own museum, which reflects a long history of bloody conflicts; the latest combatants are thrill-seeking safari customers, who hunt humans rather than game. They are led by a cynical German-American profiteer (played with zeal by Udo Kier), whose colonialist rapaciousness and cool, exploitative logic make him a close kinsman of Conrad’s Kurtz. The Bacurauans fire back with gusto. In one memorable scene, an elderly black farmer blows out the brains of a white aggressor—a quick-footed defense whose B-film gore tends to elicit gasps of awe. The dramatic crescendo echoes the ending of Mendonça’s first fiction feature, Neighboring Sounds, in which a gunshot caps a series of oppressive actions that run across generations: a white patriarch in Recife is confronted by his security man, whose roots in the backlands and trauma from the violence unleashed on his family make for an unforgettable, vengeful finale. Similarly, though Bacurau takes place in a near future, it is very much about the past, on screen and off.

In this sense, Bacurau—like the American westerns of Ford and Hawks—brims with moral complexities because of its embrace of genre, not in spite of it. To see its protagonists exalted in widescreen—a sweeping canvas of diverse faces, bodies, skin colors, and textures—is to feel the innate strength but also the inherent contradictions of the backcountry. These contradictions stem from the fact that, on the one hand, the hinterlands are enshrined in the national ethos as the quintessence of Brazilianness, yet on the other, they continue to be neglected and forgotten—until a crisis, such as the rampant burning of forests, or the murders of tribe or quilombo leaders and violent land-grabs of indigenous reserves by white farmers, force them into the spotlight. Given the far right’s backlash against human rights, the filmmakers’ inclusion of precisely those populations that are under attack—blacks, women, LGBTQ communities, other minorities—is a gesture as much of courage as it is of hope.

The two filmmakers come to Bacurau after working together for the past 15 years: Dornelles was the production designer for both Neighboring Sounds and their richly crafted middle-class melodrama Aquarius; he also worked on Mendonça’s shorts, including Cold Tropics (2009) and Electrodoméstica (“Electro-cleaning-lady,” 2005).

Together, they combine a love for classical storytelling, a prodigious lifelong cinephilia, and a strong penchant for genre, all of which sustained them over the monthslong collaborative screenwriting process. The latest result, Bacurau, is a milestone—a vigorous and angry film, like no other in the history of Brazilian and world cinema.

I spoke at length with Mendonça and Dornelles in Cannes, and seven months later, I followed up with each director separately over the phone to discuss the film’s reception and how their experiences as Latin Americans, Brazilians, and ardent genre buffs shaped their blistering portrait of a community at war.

Let’s talk about the big picture first: your choice of widescreen for this story. It’s a format that is not so common and is also challenging to stage.

Kleber Mendonça Filho: Staging is probably the biggest challenge you have as a filmmaker. It’s one of the reasons I love musicals. How to keep the frame alive with movement and brimming with energy is something that most viewers take for granted. And, of course, you can turn any film into a musical without music—that’s the whole idea for a film like Bacurau, which is about a community. Before we went on location, I was afraid that we might not find the human element that could come from 15 to 25 people appearing in the same frame. But then we worked with the outcasts in the communities: the crazy ones, poets, musicians, actors or aspiring actors, painters, sometimes just the people that others called crazy or “funny in the head”—and they’re amazing! In the film, when you look and see their faces, they’re completely into the scene. This really helps when you move the camera and zoom in, or come in from the side and use a crane.

The irony is that many people tell us that Bacurau is fast-paced, and others say it’s incredibly slow and boring. [Laughs] You really never can win!

The film is full of paradoxes. You shot it in the infamous dry lands of Brazil, and yet they look so green on screen.

Juliano Dornelles: We were very fortunate to come to the sertão when we did. From a practical standpoint, the rains made our work complicated—we lost three days of filming. But it allowed us to show the region from a different angle: green, splendid, full of life.

KMF: These paradoxes lie at the heart of our film. Bacurau is green yet dry; it’s poor but full of dignity. Its people don’t go hungry, but they are disrespected. The population is extremely pacific, yet it guards its secrets. I believe that I make straightforward films, but perhaps the way we filmed Bacurau specifically creates certain tensions. The constant shock of paradoxes elicited many different reactions from the audience—some perplexed, others a bit tense or questioning. With the foreigners, for example, it seems that viewers end up negotiating to what degree they can deal with violence, how and which moral lines are crossed—murdering a child or a spouse, or questions of who can be called “a Nazi.”

There’s also the question of who’s white and who’s not.

KMF: Even more specifically: who is white in Brazilian society. The Brazilian sertão is actually extremely white. For many, even for many Brazilians living in the South, it’s surprising to learn just how white the Northeast hinterlands are. We were ready to film in a mostly white town, but during our scouting came across a quilombo. The two communities did not mix. From then on, the unstated but crucial idea was that Bacurau is a “remixed” quilombo: a historical place of resistance, but with some white, indigenous, trans, and other inhabitants. Carmelita, the matriarch who passes away in the film, is the matriarch of the quilombo—though we never use this word.

JD: That’s why we included that the town of Bacurau has a historical museum—a museum that plays such a key role in the community, because it preserves the history of cangaço, of rebellions.

KMF: This is also why the capoeira scene, which wasn’t originally in our screenplay but came directly from our actors, is so important. I wasn’t a fan of that scene at first, but after revisiting John Carpenter’s Night, I thought that perhaps if we joined the capoeira with the sounds of feet and hands beating to the rhythm, and then the music from Night, we would have a scene of preparing for war. Even if we don’t explicitly call it that and let it figure in as a dance.

That sequence actually starts in a whorehouse—with the rhythm in a sex scene, then with the pimp clapping his hands, and then the capoeira and war.

KMF: All these rhythms and musicality are interconnected. You could say that it’s in this sequence that the film goes wild. As a number of people mentioned to us in Cannes, after this moment you truly can’t imagine what’s going to happen next. It’s great that we could enter this territory of strangeness through the music.

Speaking of strangeness—or estrangement—I wonder if that’s yet another reason for your embracing widescreen.

KMF: Cinema always relies a lot on technology. Nowadays, when I turn on the television to watch Netflix, there’s a strong possibility that all the films will look similar. The same thing happens when you go back to the late 1970s and watch Superman or Heaven’s Gate. They have a certain style that comes from the ’70s and from technology, like the negatives of that era and the choice of lenses.

As a filmmaker, I like to find something that gives me the pleasure of looking at a film, and that doesn’t look like everything else. With Neighboring Sounds I loved the idea of making a movie in kitchens and in common places, but in 35mm Techniscope, which goes against the kitchen-sink hyperrealist style. So you make a Brazilian kitchen-sink [drama] and treat it like it’s a Brian De Palma thriller from the 1980s. This probably sounds pretentious, but it does offer me a challenge. The same with Aquarius—a one-character drama, but with the widescreen [look] from Italy or from the early ’70s in the United States. With Bacurau, we really let go and embraced genre. In fact, just the other day, someone wrote on Letterboxd that Aquarius is a great thriller—and I always thought of it as a thriller. I so often read that it’s a political family drama, a film about a woman—and it is—but it’s also a suspense thriller. Now with Bacurau, the genre aspect is out in the open.

What was the process of writing this screenplay together?

JD: We had different phases, but our main phase was about eight months of concentrated writing—five times a week, 9 to 5, or sometimes 9 to 7. It was very intense.

KMF: We had deep discussions with our editor, Eduardo Serrano, about how we wanted the beginning to be very deliberate and precise in presenting the community, but also about [subverting] expectations.

Because these days, usually, within 45 seconds of a film, you get exactly what it is—and that’s precisely what we didn’t want. So let’s say that you’re watching this Brazilian film. It begins and you think, “Is it a rural drama?” Then it slowly shape-shifts into something that resembles an action or a B or a sci-fi movie, then into hardcore horror or suspense. It’s a bit like walking in a garden and finding a piece of string, and then realizing that it’s much longer than you anticipated.

I wonder about the script’s dark humor. For example, when the older black man blows up a white man’s skull—that graphic scene made some in the audience laugh.

JD: I see this kind of laughter as a release rather than a sign that our viewers find graphic violence funny. We certainly don’t. We show it as quite ugly.

But Lunga the bandit is both seductive and violent.

JD: Cosmopolitanism in banditry is now a real concept. Here we play with the idea of drag; that’s why the character has two versions of the name, masculine and feminine—Lungo/Lunga. Again, in a place like Bacurau, there is no simple way to portray a person.

That scene with the cut-off heads comes across as a pastiche.

JD: In a way, the humor was much more present in the screenplay, but then slowly the film took on a more serious tone. Perhaps that’s why we were so curious to see the film’s reception in Brazil, because for Brazilians our movie is profoundly sad. It is catharsis reached from another angle. That’s what fantastical stories can help achieve.

It seems that your actors—Udo Kier playing the villain, for example—really fed off of that fantastical energy.

KMF: Udo is a great human being. He feeds off getting to know people and making discoveries. It was a similar experience to the feeling I had when Sonia [Braga] came to Aquarius. It’s one of those rare opportunities when you step into cinema because you have the access—you can hold hands with somebody who’s been part of your life for many years. It’s a beautiful thing. I’d talk to Sonia for hours over lunch or dinner about things that are part of the history of cinema, and which are also part of her life. And the same thing happened with Udo—Dario Argento, Fassbinder, Gus Van Sant, Lars von Trier. Madonna. At one dinner, we were drinking wine and watching Madonna’s “Deeper and Deeper” music video on the phone, with Udo making a running commentary. And I realized that he appears as much as Madonna or maybe a bit more—and what a great face! We worked really hard to put that face and his dramatic physical presence in the film.

In terms of dialogue, though, I wonder if some Western viewers might find the white characters one-dimensional.

JD: I don’t agree that they’re one-dimensional. As villains, they have their own complexity. At the same time, the film takes the point of view of persons from Bacurau—our point of view, as those from Brazil’s Northeast. When you watch Hollywood films, the villains are often Arabs, or in the action films of the 1980s, they’re the Soviets. We’re working with genre cinema, and our film is about an invasion—so we naturally chose a group that is culturally very different.

KMF: One reaction at Alice Tully Hall during the New York Film Festival—a gentleman in the back asked why the Americans were the “baddies”—made me think: we’ve been watching American cinema for 120 years but it’s still rare to see a non-American film that portrays Americans as the bad guys. We’ve had Carmen Miranda as an exotic woman with fruits on her head. And can you just imagine a Brazilian, in 1938, asking a Fox executive why the Brazilian woman has fruits on her head? [Chuckles] Or a Russian 19-year-old asking an American director why Russians always smoke, kill people, and have no hair? What about the Mexican narcos in American thrillers? Soderbergh is an amazing director, but why are all the Mexican locations yellow and dusty and American ones clean and blue? I think these are all questions of representation, of how the industry has trained viewers to think of representation. So it’s fascinating how Bacurau is seen, from Australia to France, Brazil to Argentina.

Could you say more about the reception back home?

JD: In Brazil—where Bacurau has been in cinemas now for 20 weeks straight, with over 730,000 viewers so far, which is no small feat—the reception has been very strong, though not always in ways that we anticipated. Some viewers leave the cinema electrified; others are depressed, thinking of our country’s tragedy, and how we’ve gotten there. But there’s something else: in Brazil, we’ve always watched genre films, but historically, they were American or Italian, not Brazilian. That was my experience with cinephilia. So in our public’s imaginary, though genre cinema is huge, Brazilian genre is still being constructed. Of course, we shouldn’t forget the national example of Zé do Caixão [aka Coffin Joe], but he was the only one. If you mention his name to viewers who don’t work in film, they’ll most likely associate it with “trash cinema,” which is problematic.

What was your own experience of cinephilia living in Recife?

KMF: It’s like that line from Goodfellas: “As far back as I can remember…” I always went to the movies. In the ’70s, we had good commercial films and great cinemas. Movie palaces were very popular in Recife. In my teenage years, in England, we went every month to London, to museums and to Leicester Square to watch movies, often in 70mm. The first fascinating non-American film I saw was Herzog’s Fitzcarraldo, then Wenders’s Paris, Texas. It was the VHS era, so I had access to a lot of films. My cinephilia had three areas: moviegoing, VHS, and television. When I came back to Brazil in 1986, you could see a new Cronenberg at a 1000-seat commercial cinema in downtown Recife. The Fly was one of the greatest films I’ve seen in my life, and it just happened to have been released there; the same with Carpenter, Verhoeven, and De Palma. That’s what made me want to make films.

Now Cinema São Luis is Recife’s only surviving movie palace, but we’re very lucky, because in the 10 years since it ceased to be a commercial theater, it has become a very special place for culture and cinema. Bacurau has been the second-ranked movie in Brazil and 25,000 people went to see it at São Luis alone. Gabriel Mascaro’s Divine Love also did incredibly well there. It’s amazing to see people line up around the block to see movies. It doesn’t happen in many other places around the world—maybe at The Castro in San Francisco, which is another very happy experience in communal filmgoing.

I’m actually working on an essay film about the landscape around the São Luis. The city is like an animal that keeps shedding its skin and then a new skin comes in—it’s like a werewolf that changes into different animals over time. As you grow older, you begin to see the different layers of the city, because you’ve lived long enough to remember them at different stages. It’s a very personal film, about how I look at my city and its downtown area, which I really love.

Juliano, you are also working on a new project?

JD: Yes, I’m in the editing stage, but also waiting on some financing issues to get resolved. The new film is a bit like being in a long-distance relationship in an age with no internet or video chat. Your feelings change over time, and you must rediscover if you’re still in love. That’s how I feel: I need to digest it a bit more.

What energizes you about contemporary Brazilian cinema, despite the country’s current political and human rights crisis?

KMF: Depending on when you ask me that question, I’d be very sad, because we’re really seeing a destruction of something that was built very slowly and democratically. When I made Neighboring Sounds, my script was chosen because it was the first year that quotas were applied to funding first features. And historically, all the funding had been concentrated in the Southeast. So I was given a new tool that then led to my second film. But that was 11 years ago.

Today, we have a whole new group of young people making films, and with the range of themes and styles and aesthetics and skin color and geography and social layers, Brazilian cinema is even truer to Brazil than it was 10 years ago. To see it systematically sabotaged, with glee, is something that I never saw coming. But the good thing—depending on the time of day you ask me—is that there’s an opportunity to develop something out of frustration and anger, which is basically what I’ve been doing, because Brazil has always been not only a crazy place but also full of contradictions. Over the last year, I’ve been given the drug called Bacurau, to navigate this horrible, bizarre terrain. It has made me strong, in terms of developing two or three ideas that I think are true, not just in Brazil but around the world.

Ela Bittencourt works as a critic and curator in the U.S. and Brazil and consults for a number of international film festivals. She also runs the film site Lyssaria.