It’s Bound to End in Tears

It’s a love story that has been played out over more than three and a half centuries, and failed to find a happy ending. In The Four Musketeers (74), Richard Lester’s second adaptation of Alexandre Dumas—or the second half of a film surreptitiously split off from the first by the producers, according to the complaint raised by the actors—Constance Bonacieux (Raquel Welch), the mistress of young hero D’Artagnan (Michael York), is abducted. When pressed by the other musketeers about his feelings for Constance, D’Artagnan comes back stoutly: “I love her—I think.”

Flash forward—or do a radical jump cut, of the kind for which Lester was often vilified—to the flippy, trippy hills of San Francisco in 1967, and Dr. Archie Bollen (George C. Scott) being pressed that he must “feel something” for the eponymous kook (Julie Christie) in Petulia (68), who has crashed into his life. He shrugs: “I guess I do.” Lester has often declared in interviews that he is not a sentimental person, with no use for the conventionally redemptive love story. The way the story develops in Petulia might even qualify as an anti-romance, with Archie in the final scene not willing to commit himself to a life with Petulia, and her declaring: “When I lie dying, wondering what my life’s all been about, you won’t even cross my mind.”

The Four Musketeers

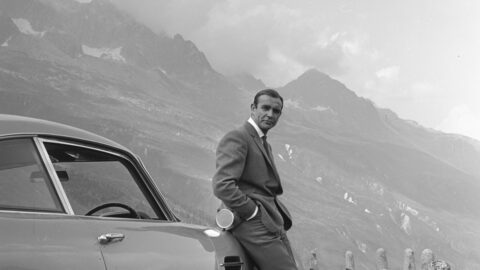

Continue the story a decade later, with Cuba (79), where Alex (Brooke Adams), is dismissing her past affair with an ex-lover (Sean Connery), which he has spent much of the movie trying to rekindle: “I regard those years spent away as lost time. There was nothing, and I include you, Robert, nothing that made them memorable.” But final words might not be the last word; they might just be another way of probing a situation that defies closure. After Archie leaves the hospital where Petulia is about to give birth, and she feels the anesthetist’s hand lowering a mask, she is startled into whispering Archie’s name (his healing hands first drew Petulia to him). And in Cuba, after dismissing Robert, Alex rushes to the Havana airport—the country is on the brink of its revolution—for a reunion that doesn’t happen. Lester is deliberately alluding to that archetypal romantic movie, Casablanca—but in order to debunk it or to include it in his own film’s texture?

Perhaps this is not so much anti-romanticism as ambivalent romanticism, love’s labour lost in a maze of qualifications and moment-by-moment hesitations. Lester’s style, with its quick changes of mood and broken connections (changes that can take place regardless of cutting speed), might almost be designed to foster ambivalence, never allowing feelings to settle long enough for characters to test whether they are genuine. Another possibility is that the anti-romanticism serves more radical ends, that it allows the films to be anti-character, in the usual dramatic sense. Characteristics are never allowed to settle long enough to form a secure identity—being subjected to pressures ranging from their social setting to the director’s willful aesthetic demands. Lester is one of the most merciless of filmmakers in making his characters ill at ease in order to have the world on screen as he wants it.

He does this in various ways. Petulia is the most forceful, cutting the unfortunate Archie adrift—he has just quit his marriage, and is at an emotional and social impasse—while subjecting him to aggressive fragments of what Lester felt, in 1967, was the decaying hippie dream of peace and love. These fragments form an intricate pattern of flashbacks and flash-forwards, which is unique for Lester, despite his reputation for the “cut-up,” for Sixties zaniness and TV commercial–type jumpiness. Here the pattern suggests something more steely, rooted perhaps in anti-romanticism, a taste for surrealist humor, and an approach to form that is anything but zany. Raymond Durgnat has compared “the oppressive cluster of distractions” in Petulia to Alain Resnais’s Muriel, “another study in the destruction of passion, of memory, of identity by an urban environment.”

Cuba

Lester was free to shape these fragments his own way in Petulia, but it is interesting to see how the pattern emerges in Juggernaut (74), an assignment that he took over from another director shortly before shooting (with some hasty reworking by television writer Alan Plater). Without the benefit of cut-ups, the central relationship between the ship’s captain (Omar Sharif) and a passenger (Shirley Knight) is just as enigmatic and stalled as that between Petulia and Archie. And there’s a minor enigmatic variation in what may have happened between a police detective (Anthony Hopkins) and his wife, who is onboard the threatened ocean liner.

In place of deliberate puzzle-making, Juggernaut goes for a masking strategy, dropping out scenes or information that would have been standard in Seventies disaster movies. If Lester likes to challenge his characters, he is also willing to discomfit his audiences. It is usually said—and Lester has said as much—that Petulia was a watershed in his career, the first time he had taken on fully rounded, three-dimensional characters after the skittering, two-dimensional cartoons of his earlier films. But the elusive, hard-to-grasp reality of his post-Petulia characters, left to their own unhappy devices while he goes looking for reality elsewhere, has its own two-dimensional quality, a vivid, even angry, pointillism of background that contends with the foreground.

There are qualities in Lester that never add to depth of characterization because they stress the surface of the picture—painterly qualities obscured by all the discussion of his “Swinging Sixties” editing style. In between the vigorous dueling exploits of the musketeers, there are scenes that seem composed just for visual appeal: the four of them in a row, feet up on a table laden with food, a silent scene of contented gluttony, which makes them look like cavaliers from a Frans Hals painting. Lester’s taste for surrealism had been advertised in Petulia, with a print of Magritte’s The Ladder of Fire in Archie and Petulia’s unhappy motel room. But his own most striking surrealist image, in The Four Musketeers, begins with a tub of bath water, dyed red from a dripping wound, out of which a strange, patchwork submersible then seems to emerge—which proves to be a craft being tested on an English shore.

Petulia

And the loneliness and emptiness of Petulia was already there in Help! (65), the second Beatles film. The celebration of the band as performers in A Hard Day’s Night (64) has been replaced by something post-performance, post-sexual-energy. The songs here all seem to be about relationships as lost or stymied as Archie Bollen’s: “She said that living with me was bringing her down”; “Feeling like this I just can’t go on anymore.” The personalities of the Fab Four are meanwhile scribbled in the margins of a nonsense plot. John Lennon later complained that they had become extras in their own film. Lester put this down to the way the Beatles themselves restricted what could be shown of their real lives, but the complaint stayed with him as a useful conceptualization. Cuba, with Connery’s mercenary and assorted seedy characters being overwhelmed by Castro’s revolution, he called “a film about extras.”

The question arises as to whether all Lester’s films are populated by extras, especially the ones in which the central role is always a tribe of four: the four tenants of London suburbia in The Knack… and How to Get It (65), the Fab Four, and the four musketeers. They are, in a way, if not sideline figures, then fantasized or splintering fragments of a social reality that may absorb, reduce, or cruelly expose them. The Knack actually allows a romantic couple to walk off at the end accompanied by a firework display, while the previously self-assured, self-defining possessor of the knack has to join the anonymous chorus of (older) voices who have tut-tutted throughout at the group, or at their generation, or actually at anything at all that might provoke their conventional/absurd response (“They’re a new brand of person altogether”; “It’s bound to end in tears”; “I blame the internal combustion”).

Defining the Lester approach, the Musketeers films allowed him to situate popular heroics and cinematic spectacle in a world that demanded attention in its own right, with exciting possibilities for historical research. While preparing the project, he said in an interview with Sight & Sound: “I’m going to make the film set quite purely in its social structure . . . How did people talk? What did they eat? How did they brush their teeth? . . . What it meant having no sanitation . . . What would your life expectancy have been?” None of this emerges as explicit information, of course, but as asides (casual street dentistry), glimpses of the literal market economy of the day.

The Knack... and How to Get It

In the context, this has to play first as comedy, as cinematic invention before historical instruction. The films work hard to insist on two levels of life, a world of “doing” or “being” beneath the business of the plot and the action heroics. A courtier sits up to his waist in a marsh to release the birds for the king’s falcon to swoop on while the court ladies titter; sedan-chair bearers sigh when their aristocratic passenger alights (“She’s put weight on”; “Why doesn’t she get a horse?”). The verbal asides are as important as the visual, creating a “second” world that pokes fun at the first but also floats free of it and is a minor abstract narrative, because the comments are often not linked to a speaker.

Producing this secondary narrative also takes some of the air, the motive force, out of the primary one. It’s a political move of sorts. Lester is happiest when he has a “service economy” to drift away to. Keeping the cruise ship Britannic afloat in Juggernaut is as labor-intensive and hierarchical an operation as maintaining the court of Louis XIII. It attests to Lester’s willingness to push his subject around; to treat his major characters as evidence of a problematic situation that’s not theirs alone. As the Musketeers films proceed, the foursome’s willingness to spring into action at some royal whim (or to save a royal folly) looks less and less heroic (“Let’s go and be killed where we’re told to”). By the end, when Athos (Oliver Reed) asserts his former nobility as M. le Comte de la Fère and avenges an affront to that nobility by executing Milady de Winter (Faye Dunaway), it looks like something quite the opposite.

With the heroes reduced in this fashion, if not exactly to extras then to compromised players in the royal game, the moral force of the films, as well as their narrative impetus, really derives from the character advertised as the arch villain, Cardinal Richelieu (Charlton Heston). This happens elsewhere in Lester: his Sheriff of Nottingham (Robert Shaw) in Robin and Marian (76) is viewed with remarkable sympathy, as a force of progress in a backward age—“I can read and write. Makes you suspect”—of which Robin and his men are a part. Narrative drive, like positive characters to propel his plots, is something Lester may actually work against, while searching out other areas of interest, suitable subjects for research.

Robin and Marian

Richelieu and the Sheriff of Nottingham could be joined by the most curious of the villainous authority figures in Lester’s films—the German officer called Odlebog (Karl Michael Vogler) in How I Won the War (67), who captures Lieutenant Ernest Goodbody (Michael Crawford), the jingoistic but inept platoon commander, while he is attempting a victorious crossing of the Rhine in 1945. (“Odlebog” is a nonsense name that is halfway to an anagram of Goodbody.) The rest of the film is told in flashback while the two officers get to know each other, and Odlebog makes Goodbody more comfortable with his class prejudices and the inherent fascism in his careless, schoolboyish attitudes (“War is without doubt the noblest of games”). Goodbody finally confides to his counterpart: “I haven’t been able to speak to anyone else through the whole of this film.”

It may be a measure of these characters’ “villainy” that they expose the falseness, the everyday villainy, around them. They point up everything else as a fair target for satire and surrealist humor. This is most extreme in How I Won the War, with its doubly undermined narrative: the action is a string of lethal non sequiturs mocking not just war but war films (even the conventional antiwar war film). According to Lester, this was “consciously and determinedly” Brechtian. Which suggests how his anti-narrative and anti-character impulses might work toward something really negative, an ultimate reductionism.

This could be The Bed Sitting Room (69), an absurdist vision of a post-nuclear world in which the story is really just the landscape—alternately radioactively garish and dead-zone gray—through which a handful of “the 20 people who are known to be left alive in England” bemusedly wander. There’s a suburban haplessness about this nuclear apocalypse, with a “keep calm and carry on” spirit trying to emerge: it’s not unlike the suburban world of Help!, or the “nameless” town in Lester’s first musical feature, It’s Trad, Dad! (aka Ring-a-Ding Rhythm!, 62). The Bed Sitting Room was made when Lester had his greatest financial control, but did so poorly that he couldn’t make another film for four years. Seeing how far he could go on so little, Lester perhaps went too far: “the limited resources of a desolate landscape,” he said in a Movie interview, made it “very difficult to create a sustained visual and emotional interest.”

The Bed Sitting Room

There is a positive charge to the film, however. It ends with a vision of new growth sprouting, “a time of peace, prosperity, and stability” ahead, and redemptive love in the offing. This is as absurd as anything else, of course, but it’s revealing that it would take this specter of the end of all things to produce a lyricism in Lester (and perhaps frame a new beginning). There’s something similar, in equally symbolic terms, in Robin and Marian, which is perhaps Lester’s most complete love story. Its limits in human terms are signaled at the beginning (a pair of apples on a sill are seen to be moldering—the aging Robin and Marian?—before the opening credits are over) and made absolute at the end, when an arrow fired through a window marks the spot where the two lovers will be buried.