No film captures the glittering, zombified world of yé-yé pop royalty with as much style as Marc’O’s 1968 musical Les Idoles. Seen today, this flamboyant tale of complicity and revolt yields multifaceted readings—as backstage drama, as denunciation of consumer capitalism, and as the historical record of a crucial meeting between commercial auteurism and the avant-garde. Think of it as an all-singing, all-dancing missing link between the melancholy pop fantasy of Godard’s Masculin-Féminin and the aerial views and blank screens of Guy Debord’s Critique de la separation.

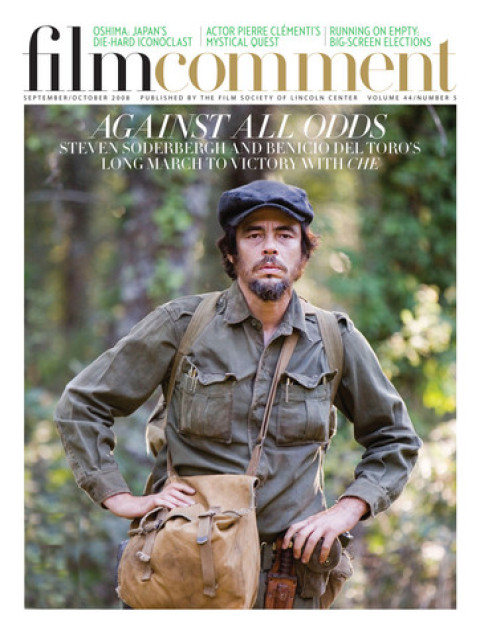

Like Debord, director Marc’O began his career close to the Lettrist movement and experimental cinema. After producing Isidore Isou’s Venom and Eternity, making a first feature (Closed Vision, 53), and editing the influential but short-lived film journal Ion, he began to drift from film to theater in order to pursue intensive work with actors. In the late Fifties he joined the thriving artistic community at Paris’s American Center and founded the improbably named Center for Theater and Experimentation on Actor Performance (while elsewhere in the building Yves Klein gave judo lessons and Henry Miller swam in the nude). He quickly attracted a motivated troupe of almost-unknowns—Jean-Pierre Kalfon, Bulle Ogier, Pierre Clémenti, and Michèle Moretti, among others—and built up a repertoire of original works like Les Bargasses, a play about an army colonel’s wartime visit to a whorehouse that impressed Jacques Rivette so much that he constructed L’Amour fou around Kalfon and Ogier, two of its stars.

The stage version of Les Idoles was among the group’s last and most successful productions. Teetering on the verge of chaos (there was a standing offer of free tickets to anyone who rode into the theater on a motorcycle), its open structure and physically demanding roles recalled the confrontational performance ethic of The Living Theatre. The story was simple: three pop singers—reformed Brechtian delinquent Charly the Knife (Clémenti), fausse naïve Gigi la Folle (Ogier), and part-time psychic Simon le Magicien (Kalfon)—see their initial success give way to betrayal, conflict, and disillusionment. Though it narrates a decline, Les Idoles avoids the orgies and overdoses of rock mythology’s late-period primal scene in order to raise broader questions about economic systems. By dealing with pop stars, Marc’O re-frames Situationist theory as individual experience: in essence, he shows us living representatives of the Society of the Spectacle eaten alive by their own image.

When the offer came to turn the play into a film, Marc’O kept its skeletal plot, retained most of the cast (which also included underground figures like Daniel Pommereulle and actual pop singers like Valérie Lagrange), and expanded the production team, notably adding André Téchiné as assistant director and Jean Eustache as editor. (Eustache was especially proud of his work; rumors abound of a phantom print of The Mother and the Whore with an extra scene set at a screening of Les Idoles.) In order to move past the spatial constraints of theater, Marc’O also asked Paul Virilio and architect Claude Parent to help choose locations that could enhance the action. The film plays on the disjunctions between these varied settings, making baroque associations and head-scratching leaps from place to place and never bothering to tie anything together. The splintered landscape underscores the protagonists’ personal fragmentation. Both the on-screen world and the characters who inhabit it are depicted as pure products of an alienated culture that remains incapable of authenticity, clarity, or coherence.

And yet, like the finest moral tracts, the film’s critique of the culture industry is also its own form of fetishism. Little by little, the accusations it levels are drowned out by the sensual appeals to props, costumes (wait till you see the costumes), or, more simply, bodies in motion. Marc’O is clearly in love with his actors, and frames them with such care that even their clumsiest gestures appear epic. The performances he elicits are unforgettable: Ogier’s crass, hunchbacked moves dovetail perfectly with Clémenti’s convulsive lyricism and Kalfon’s star turn, which calls to mind Frankenstein’s monster cradling an armful of puppies. The three leads become endearing, grotesque giants whose every sigh and high kick is echoed in the freaked-out, punked-up musical backing of house band Les Rollsticks. The sheer rush of all this frenzied action complicates easy readings of Marc’O’s work. While the film tears down existing idols, it is also responsible for creating new ones. Ultimately, it is this sly coupling of censure and caress that lies at the heart of its cruel genius: first it suggests that pop music is the sound that kills—then it makes us want to hear more.