I’ve never been convinced that Brian De Palma’s baroque displays of violence against women are a useful way of commenting upon misogyny—but all the same there’s something perceptive and accurate about the female vivisections in Passion. Embedded in a characteristically convoluted narrative replete with absurd twists that toy with audience expectations, said acts are no less gruesome than usual for a De Palma film, but they’re carried out by icy, corporate schemers who repurpose and manipulate feminist ideals for personal gain without batting their eyelashes.

Passion is set in the world of multi-national advertising (where the feminist “message” was distorted and yoked to commercial ends early on), and De Palma’s characters use the tools of their trade to destroy each other. Pasty, muted corporate underling Isabelle (Noomi Rapace) devises a “revolutionary” viral ad campaign by sticking a cell phone in the back pocket of her sylphlike assistant’s jeans and creating a montage of all the people (from dirty old men to new mothers) who check out her ass. Trouble arises when Isabelle’s Hitchcock-blonde boss/frenemy Christine (Rachel McAdams) takes credit for her idea during a meeting in order to secure a promotion, assuring her after the fact that “there’s no backstabbing here—this is business.” After the predictable failure of this lazy attempt at sisterhood, and despite Christine’s more nuanced attempts to ingratiate herself with Isabelle (buying her Sarah Palin–red high heels, plying her with booze, kissing her, and begging for her love), Isabelle opts to reassert her ownership of the campaign by uploading the video to YouTube, where it garners 10 million views in a matter of hours. The result is a promotion to the position for which Christine had been jockeying (suggesting the interchangeability of female labor in the eyes of male bosses). Once the gauntlet has been thrown down, Christine’s campaign of psychological warfare takes a malicious, very public turn, and Isabelle descends into a sleeping-pill-induced haze of self-doubt.

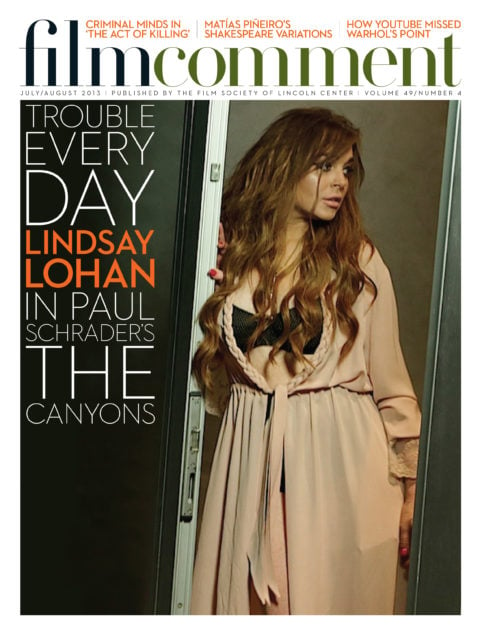

Or does she? The oneiric left-turn at the end of the second act—in which De Palma’s preoccupations with doubling and doubt go into overdrive and undercut any semblance of realism—is marked by an elegant extended split-screen sequence and topped off with a throat-slitting (chaste by contemporary standards). Of course, these doublings—be they structural, visual, or subtextual—are echoed by the reflective surfaces of the glass and polished-steel interiors, in which there is always at least one glowing screen and surveillance cameras document every supposedly private moment. Since most of these corporate spaces are devoid of natural lighting, it’s not always immediately apparent how much time has transpired between scenes, leading to a dreamlike blurring. (Whether the whole film takes place over a period of weeks or days is also ultimately unclear.) De Palma’s commitment to this simultaneously sleek and bland mise en scène leaves you with the feeling that the entire film is taking place inside an Apple Store. In one scene, an emotionally exhausted Isabelle stands framed in a glass doorway after her co-workers have gone home: her reflection and shadow suggest a domineering yet lonely figure. Her personal life is in a shambles thanks to Christine, and her identity has been reduced to her position in the workplace.

Most of the plot and Christine’s cutting remarks are preserved (word for word) from Alain Corneau’s 2010 Love Crime, the Gallic, All About Eve-inflected original. But De Palma imbues his version with a distinctly Eighties vibe, mostly thanks to the actors’ facetious delivery of laconic dialogue, framing (which self-reflexively invokes some of his own golden-era work), and Pino Donaggio’s soundtrack. Precise in its aesthetics, it's an excellent late-period work that shows, without being over-bearing, how the ascent of the corporate ladder can sometimes be a descent into a deeper circle of hell.