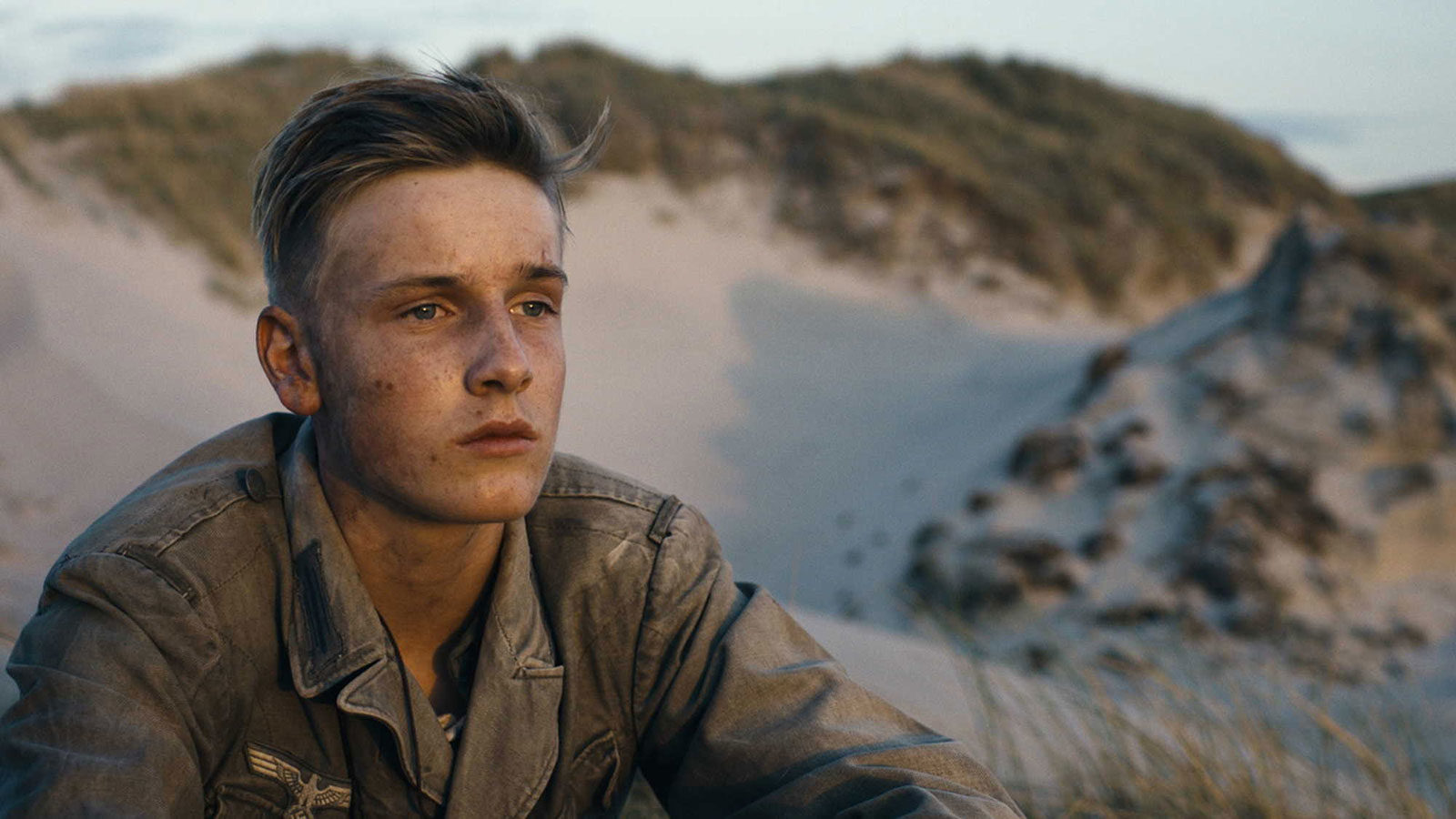

Review: Land of Mine

Martin Zandvliet’s Land of Mine takes on an obscure and fraught area of World War II history: after the end of the conflict, a newly liberated Denmark forced Nazi prisoners of war to clear the country’s beaches of more than two million landmines laid by the Reich in incorrect anticipation of an Allied invasion. The film spotlights the injustice of this situation by following a unit of wet-behind-the-ears German soldiers as they form a makeshift bomb squad—the boys look barely old enough to shave, let alone defuse lethal subterranean explosives sans protective gear or equipment.

German-hating Sgt. Rasmussen (Roland Møller) is placed in charge of the dozen or so POWs, and the film focuses on his transformation from an abusive, coldhearted martinet into a sympathetic father figure as he begins to view the boys with humanity. Watching a teenager’s arms get blown off will do that, but Zandvliet also depicts the professional boundaries Rasmussen must transgress, and the difficult choices he must make, in order to obey his conscience: to sustain morale he lies about the fate of a killed soldier, and he even pilfers military provisions for his unit in order to counter the starvation diet the Danes impose on the Germans. (One boy steals from a nearby farm in order to help his comrades, but the rat excrement-laced animal feed poisons his platoon.)

The Germans, however, barely register: there’s a pair of twins (Emil and Oskar Belton), a naysayer (Joel Basman), and a leader (Louis Hofmann), but none of the others come across with full dimensions. In a sense, Land of Mine makes the soldiers mere fodder for tense scenes in which anyone may be loudly and violently eviscerated at any moment. Yet such lack of character development wouldn’t be so significant if it didn’t converge with the sidestepping of larger issues. The subject matter contains rich ethical quandaries and moral ambiguities, but on several points Zandvliet—who both wrote and directed the film—makes things easy for himself. The Germans, for instance, possess no backstories, and we never learn what they did on the battlefield. I understand that even if they did horrible things their actions could be explained as the product of Hitler Youth indoctrination, but it doesn’t seem right that the only information we learn about the soldiers is what they want to do when they return to Germany, all so that their inevitable deaths appear even more tragic. Beyond that, in order to clearly and pedantically define good and bad instruments of the military, Zanvliet makes Rasmussen’s superior unwaveringly cruel in his treatment of the prisoners, and there’s a scene involving their redemption via the rescue of a little girl that feels dramatically cheap.

A few aspects of Land of Mine (Denmark’s submission to the Foreign Language Film category in this year’s Oscars) offer compensation. Møller brings both an intimidating and vulnerable physicality to his portrayal of Rasmussen, whose multiple shifts from patriotic resentment of his unit to genuine care and concern for his men always feel natural; the main setting at the Danish North Sea Nature Park provides beautiful beaches, dunes, and distant squalls that are hauntingly photographed by cinematographer Camilla Hjelm. But the fact remains that Zandvliet’s film renders a wrongly forgotten episode of World War II largely forgettable, all the way up to a feel-good ending that completely elides its less-than-feel-good consequences. Many moral grey zones existed during the war and its aftermath, and in the last couple of decades several films—The Grey Zone (2001), Son of Saul (2015)—have ventured to examine the thorniest moral tangles of the war. Land of Mine is content to depict this particular one almost entirely in black-and-white terms.

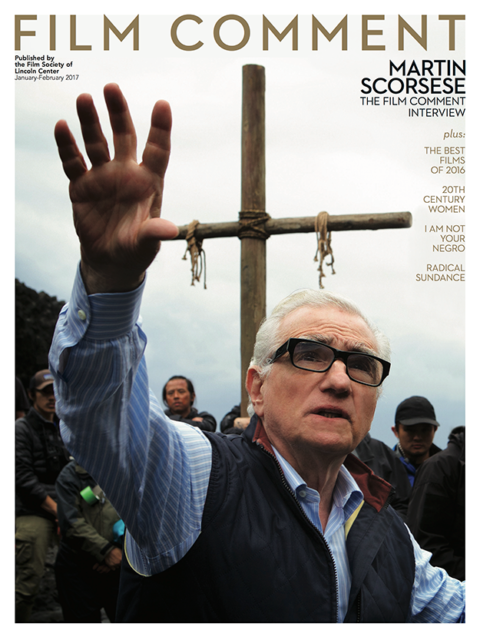

Michael Joshua Rowin is a freelance film critic who writes for Film Comment, Brooklyn Magazine, and Reverse Shot.