Review: Ex Libris: The New York Public Library

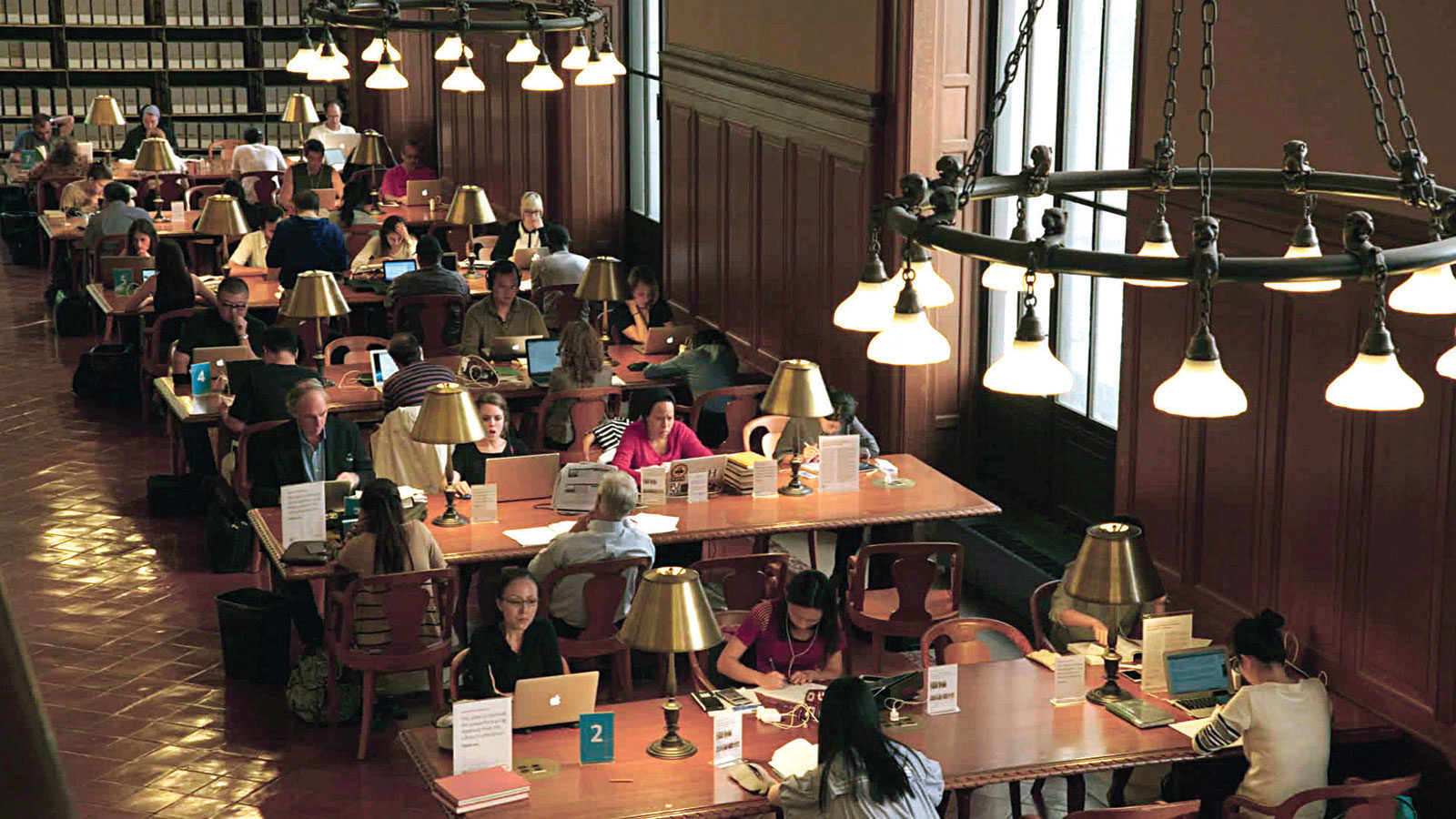

Over a hundred years ago, steel billionaire Andrew Carnegie funded the construction of New York City’s branch library system. Power created knowledge, one might say, and in Ex Libris: The New York Public Library, Frederick Wiseman surveys the institution and, in the process, reexamines how knowledge can be power. And I do mean process: Wiseman remains voracious for the stuff of daily life. He shows us people reading, researching, and surfing the Web, administrators circling round policy, the star speakers at public events (from Ta-Nehisi Coates to Patti Smith), the library’s classes and reading groups (serving ages 8 to 80 and beyond), the fundraisers for shaking the trees, and the vital community role of library spaces in informing citizens and allowing the airing of concerns. You can almost see the filmmaker grabbing armfuls of flyers about NYPL events, activities, and offerings—its ongoing, citywide yet low-profile feast of engagement and learning—and working a highlighter down to a nub.

At the same time, thanks to Wiseman’s editorial selections, Ex Libris becomes a breathtaking work of erudition, attaining Godardian or Straubian levels of quotation and association. Among the referenced and discussed on screen are Karl Marx, Orientalism, George Fitzhugh, Albrecht Dürer, Malcolm X, and Primo Levi—not to mention the in situ arts and letters of Coates, Smith, Miles Hodges, and Elvis Costello. Which gets us closer to the heart of Wiseman’s genius: through—not despite—his granular detail and editorial collage, he in fact shoots a living cinema of ideas constantly reflecting on the way we live as a society. With a detectable urgency, from At Berkeley (2013) to National Gallery (2014) to In Jackson Heights (2015) and now Ex Libris, the 87-year-old master has of late been reflecting upon participatory democracy and the public space, and the hard work and the satisfactions of each (as well as the hard work of… hard work).

Wiseman is constantly finding solutions for how to represent such ideas—and thinking itself—and in Ex Libris, he even has fun portraying the experience of reading, most amusingly in a breathy audiobook recording session of Nabokov’s Laughter in the Dark. The resonance of reading leads him to some deeply personal emotional truths, as when a retiree group analyzes Love in the Time of Cholera through the lens of decades of their own experience, in a sequence that puts the lie to the notion of individual psychological arcs as the prime guarantor of documentary insight. It’s but one example of how the pedestrian environs of NYPL auditoriums and meeting rooms provide the stage for stand-up-and-cheer moments of wonder, often shepherded along by the system’s self-effacing rank-and-file. An impassioned performance by Hodges, a dazzling New York poet, single-handedly rejuvenates the art of oratory. A demonstration of ASL for a public audience becomes enormously evocative when the Declaration of Independence is used as an example: we see how it might be signed when it is read aloud in anger, and when it is read as a plea to a king.

That scene alone may bring a patriotic tear to the eye, yet Wiseman also, like a melancholy refrain, keeps returning to the lasting American wound of race. Physically speaking, the film visits and revisits staff meetings and the 42nd Street research library while radiating out to the city’s local branches and contrasting clientele and services: from Greenwich Village’s Jefferson Market, which resembles a well-kept Ivy League reading room, to the humbler Harlem River Houses branch, to the handsome Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture—where we glimpse a T-shirt reading “Gentrification is the new ethnic cleansing.” In these tours and in its quotations, Ex Libris considers the question of historical narratives and the myriad ways they’re shaped, maintained, and in turn shape lived reality. An adult education class spotlights the jaw-dropping arguments of pro-slavery Southern theorist Fitzhugh about capitalism and slavery, while elsewhere Coates calls out the whataboutist rhetoric of black-on-black crime. Race has been a consistent concern of Wiseman’s: the centerpiece of his second New York film, Welfare (1975), set at a Manhattan public assistance office, is a ready-for-present-day-Twitter debate between a racist white WWII veteran seeking welfare and a black guard, who just happens to be a Vietnam War veteran himself.

For all the behind-the-scenes incremental decision-making on view—Wiseman is the poet laureate of the staff meeting, where lives are changed little by little—Ex Libris does underplay the recent strategic crisis under much-featured NYPL president Anthony Marx, which threatened to gut the 42nd Street research library and spin off branch buildings under dubious terms. But those controversial plans still reverberate in the film’s meeting mantra of balancing public and private partnerships, its boons and its dangers. Above all, Ex Libris reaffirms Wiseman as an essential American artist of our time, and, in an era of crumbling institutions and cratering civic awareness, an exemplary observer and thinker.