Review: Court

Despite the suspense promised by its trailer, the case at the center of Court, the first feature from writer-director Chaitanya Tamhane, is strictly a point of departure. With mixed results, the trial of a dalit (or “untouchable”) activist on trumped-up charges serves as an axis along which a broader meditation on the malaise of a modernizing urban India and its professional class is drawn.

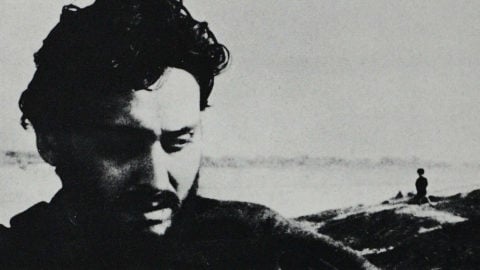

The activist, Narayan Kamble, played with earthy conviction by Vira Sathidar, is a performer of marathi dalit poetry—an amalgam of words and music performed in open-air settings to audiences of those most affected by the social neglect and exploitation characteristic of India’s hyper-developing cities. His arrest during one such performance, in connection with the death of a manual sewer cleaner in a Mumbai slum, serves as the film’s ostensible foreground.

Kamble’s defense is taken up by a successful yet frustrated human-rights lawyer, Vinay (sensitively portrayed by Vivek Gomber) and dragged through the court system slowly and arduously. Witnesses fail to appear, evidence falls through, and the outdated anti-sedition and obscenity laws used to charge the defendant are tussled over, often comically.

But Kamble’s story quickly fades into the background as we are drawn into Vinay’s world: there are family quarrels over money, a double date at a swanky lounge where a singer coos in Portuguese, and wine and cheese shopping at a boutique supermarket that would make Dean & Delucca proud. Indeed, revealingly, this dissonance between Vinay’s private and public life are the crux of the film: a young, secular, privileged yet socially minded man who cannot bear the India he would so passionately defend.

The narrative then shifts to the prosecutor (a masterful Geetanjali Kulkarni), to provide context for her reactionary and literal interpretation of the law. Once again, we enter a private world and play fly on the wall, this time to a conservative, working mother. In one important scene we accompany her family to a right-wing, xenophobic minstrel play touting the superiority of Maharashtrians (those with familial roots in the state of Maharashtra) and exhorting the audience against those “immigrants” who would take their land, jobs, and daughters.

But these digressions, if seen as the true thrust of the film, have much to offer. For most of the time, the camera is a slow, stationary witness. This risks monotony but also yields wide, detailed frames in which minute actions unfold seamlessly around the central event, capturing something of the infinite motion of India: notary hawkers outside the courtroom, sleeping spectators within, or, most beautifully, the butterfly-like machinations of the newspapermen composing the day’s paper. Often we are watching someone listen, which stretches our patience but on occasion rewards us with subtle nuances in language and expression.

There is, however, a human cost to this approach. The film’s premise of a man’s death at the hands of a cruel system of caste-based oppression seems thoroughly lost. It is not until nearly the end, during the testimony of the dead man’s wife (a powerfully understated and dignified performance by first-time actor Usha Bane) that we are reminded of the humanity behind the broken proceedings, and poignantly so.

In Jai Bhim Comrade, Anand Patwardhan’s tough and compassionate 2011 documentary on discrimination and protest within the dalit community, there is a moment of grace when a folk singer extols the great dalit leader B.R. Ambedkar, quoting his thoughts on God: “Who made Ganesh? Was it God? No, it was a potter. God is not in temples and idols, God is in service to the poor.”

When Kamble returns to breathe life into the film again, his words are more pointed: “Truth has lost its voice in all this talk of aesthetics… We will be very grateful if you do not call us artists!” After a coda in which we see the judge on vacation, that directness feels like a blast of cool air in the moral and existential desert that is justice in this Indian court.