Readings: Unstoppable

Music by Max Steiner: The Epic Life of Hollywood’s Most Influential Composer

By Steven C. Smith, Oxford University Press, $34.95

Film score composers may have faced the steepest uphill battle when the movies began to talk. In a new book on Max Steiner, Steve C. Smith quotes Oscar Levant on a post–Jazz Singer producer’s incredulous reaction to a new kind of music cue: “‘But where would the audience think the orchestra is coming from?’” More than any other composer for the screen, Steiner met the challenge of establishing and refining a musical language for narrative film head-on.

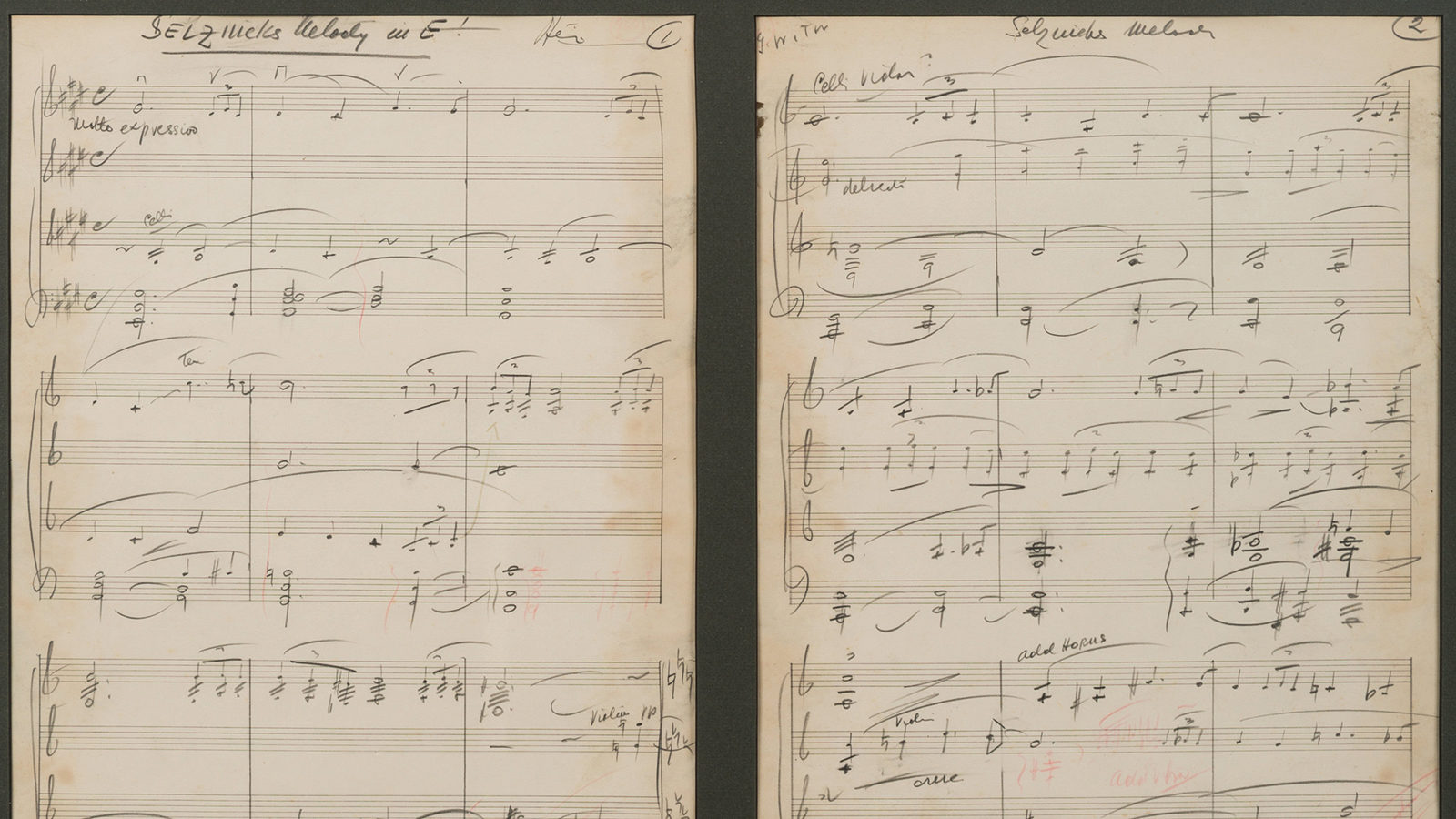

“Concert music is full of secrets,” one colleague, Rebecca composer Franz Waxman, observed. “Film music must make its point immediately.” To that end, Steiner considered individual actors’ voices when orchestrating instruments, so neither dialogue nor score would cancel the other out. Tasked with providing a live synchronized off-screen orchestral accompaniment for a solo tap dance on a large set in The Gay Divorcee, Steiner kept his musicians playing a quarter-second ahead so that the music’s notes and Fred Astaire’s taps arrived at a single microphone used to capture both sound sources at the same time. Comments scattered throughout Steiner’s original, hastily and obsessively created multicolored pencil scores document both an astute command of storytelling and a stag-party sense of humor. King Kong’s famous digital examination and appreciation of Ann Darrow rates a tongue-in-cheek admonishment to Steiner’s copyist: “WATCH PICTURE – STINK FINGER.”

The book’s description of Steiner’s Viennese entrepreneur father and his “peripatetic theatrical career blending ‘high’ and ‘low’ art” also adds context to the composer’s enormously influential fusing of classical concert music motifs to Hollywood genres. Smith also unblinkingly documents the composer’s like-father-like-son failings as a workaholic absentee spouse and parent, compulsive gambler, and spendthrift. “If I wasn’t ‘just a little off,’” Steiner wrote to then-boss Jack Warner after a salary and workload dispute, “I couldn’t do the kind of work that I’m doing.” That confession could have been his epitaph, as Music by Max Steiner details mountains of debt, multiple divorces, and a steadfast refusal to grow in any way except creatively.

The book’s description of Steiner’s Viennese entrepreneur father and his “peripatetic theatrical career blending ‘high’ and ‘low’ art” also adds context to the composer’s enormously influential fusing of classical concert music motifs to Hollywood genres. Smith also unblinkingly documents the composer’s like-father-like-son failings as a workaholic absentee spouse and parent, compulsive gambler, and spendthrift. “If I wasn’t ‘just a little off,’” Steiner wrote to then-boss Jack Warner after a salary and workload dispute, “I couldn’t do the kind of work that I’m doing.” That confession could have been his epitaph, as Music by Max Steiner details mountains of debt, multiple divorces, and a steadfast refusal to grow in any way except creatively.

Smith poignantly knits Steiner’s failing eyesight, ebbing financial prospects, and fraying familial bonds into a real-life third-act climax that would not be out of place in such Steiner-scored melodramas as Mildred Pierce or Dark Victory. Appalling personal tragedy trumps a final professional triumph, and closes out the composer’s life and Smith’s biography with such honest irony and pathos that I cannot bring myself to spoil the ending here.

The meticulously compiled trove of research and cannily contextualized analysis capture both an artist and his industry with gloves-off candor and deep affection. Music by Max Steiner reminds us that Casablanca, Pursued, King Kong, The Searchers, The Big Sleep, The Letter, and the rest of Steiner’s—and Hollywood’s—formidable canon owe their staying power to craftspeople who devoted their messy, damaged, obsessive lives to the perfection of streamlined commercial entertainment.

Bruce Bennett is a TV writer, producer, and recovering film critic.