Readings: Seduction: Sex, Lies, and Stardom in Howard Hughes’s Hollywood

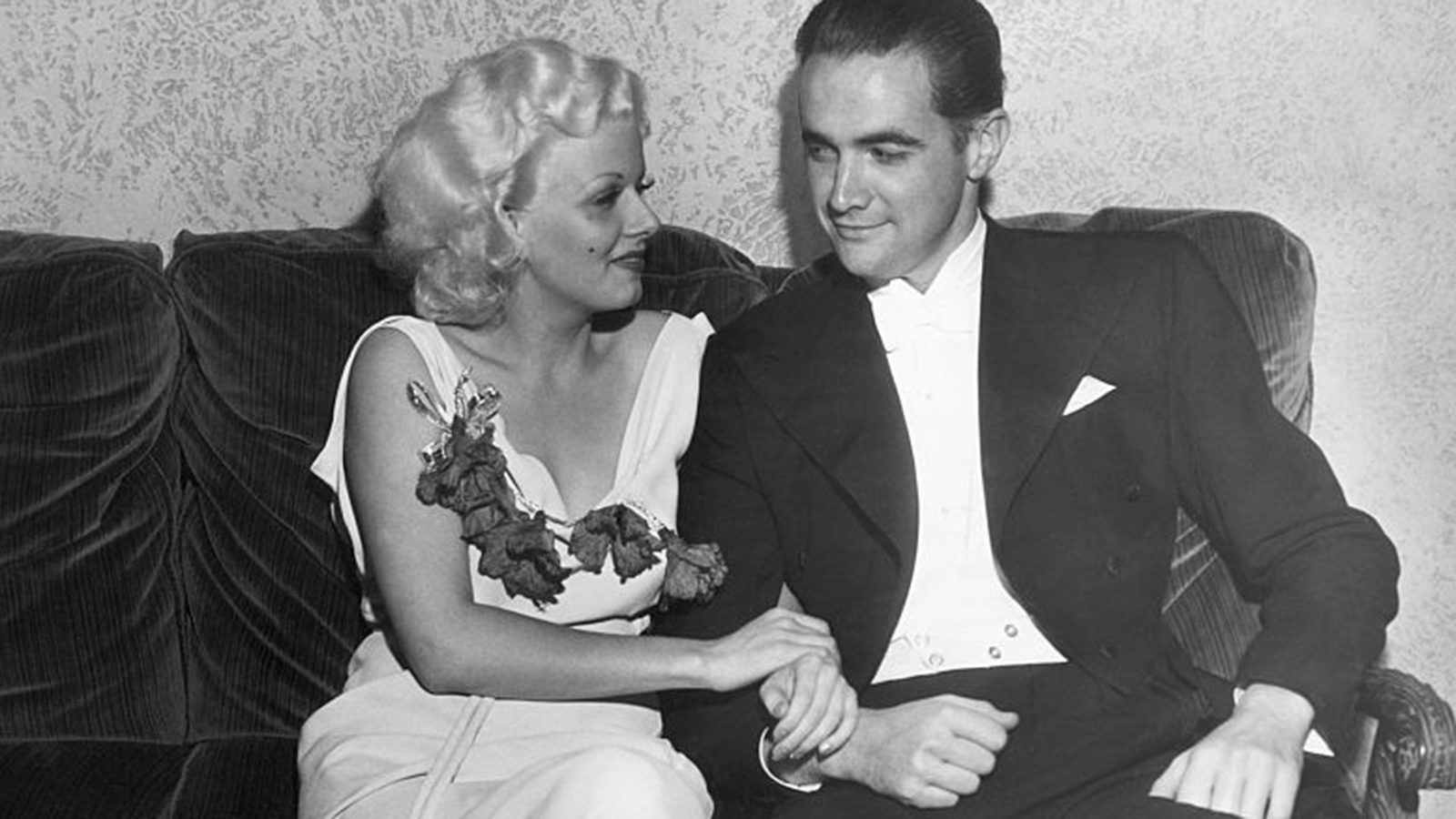

While Karina Longworth’s Seduction: Sex, Lies, and Stardom in Howard Hughes’s Hollywood sticks to the facts culled mostly from primary sources, her book is juicier than the most salacious legends about the notorious playboy and producer of the title. Hughes made stars of Jean Harlow and Jane Russell, numbered Katharine Hepburn and Ava Gardner among his consorts, and still had time to run TWA Airlines and RKO Pictures and mint billions (in today’s dollars) as a defense contractor. But why, asks Longworth, should the guy she characterizes nicely as an “increasingly eccentric, head-traumatized megamillionaire” still be extolled for his womanizing?

Seduction frames Hughes as the prototype of the Hollywood mogul/predator, antecedent of Harvey Weinstein and Les Moonves, those Casanovas of the casting couch. Longworth, film critic, biographer, and host of the podcast “You Must Remember This,” comes out to “rethink stories that lionize playboys, that celebrate the idea that women of the twentieth century were lands to be conquered, or collateral damage to a great man’s rise or fall.” So, this is not a biography. It is a matter-of-fact history of Hughes’s relationships with women as seen through feminist eyes. And it is eye-opening.

Seduction frames Hughes as the prototype of the Hollywood mogul/predator, antecedent of Harvey Weinstein and Les Moonves, those Casanovas of the casting couch. Longworth, film critic, biographer, and host of the podcast “You Must Remember This,” comes out to “rethink stories that lionize playboys, that celebrate the idea that women of the twentieth century were lands to be conquered, or collateral damage to a great man’s rise or fall.” So, this is not a biography. It is a matter-of-fact history of Hughes’s relationships with women as seen through feminist eyes. And it is eye-opening.

For Longworth, Hughes personifies the many ways that women were Hollywood commodities, whether seduced with the promise of a studio entrée, bought and exchanged like props, or used as eye candy to certify their escort’s studliness. Hughes was the master of such transactional liaisons. Where movies such as The Aviator celebrate him as a cocksman, the gimlet-eyed Longworth correctly regards him as a cock-and-bull artist when it came to women.

While making his 1930 aviation epic, Hell’s Angels, Hughes stalked actress Billie Dove, whom he effectively bought from her husband to secure their divorce. The price tag was $350,000—the equivalent of $5 million in 2018. One woman was never enough, notes Longworth, who writes that as Hughes aged his relationships were less about sex and more about control. At one point in the 1950s he had a wife (his third) and handfuls of young girls installed in houses nearby or bungalows at the Beverly Hills Hotel, pinballing among them. Like iron filings to magnet, ingénues were drawn to Hughes because of his reputation as a starmaker, which mostly involved pouring Harlow and Russell into body-revealing clothes that emphasized their breasts. “The roles got bigger,” said Russell ruefully, “the costumes got smaller.”

The book is mostly but not exclusively about exploitation, big bucks, and boobs. Still, in chapters chronicling his relationships with Hepburn and Ida Lupino, Longworth shows Hughes capable of benevolence. When RKO terminated Hepburn’s contract, Hughes bankrolled her stage comeback vehicle, The Philadelphia Story, advising her to option the movie rights. That move secured her film career. Similarly, in the 1950s Hughes contracted with Lupino, whom he’d dated in the 1930s, to distribute the films she directed through RKO, which he then controlled. My advice: come to Seduction for the deep dish, but stay for its perceptive discussion of movies and film history.

Carrie Rickey is senior book critic for Film Quarterly, film critic emerita of The Philadelphia Inquirer, and movie critic for Truthdig.com.