Interview: Quentin Tarantino

It may be that writer-director and sometime actor Quentin Tarantino is to video-store clerks what the French Nouvelle Vague, Peter Bogdanovich, and Paul Schrader were to several generations of movie critics—proof that it’s possible not only to slip through the looking glass of film history and go from spectator to participant but also to have a decisive influence on that history in the process. Tarantino’s 1992 debut, Reservoir Dogs, will, I think, prove pivotal in the history of the American independent film, for legitimizing its relationship to Hollywood genre.

Tarantino’s new film Pulp Fiction consolidates his reconciliation of the American hard-boiled pulp tradition since the 1940s with the post-Pop idiom that dates from the ’60s. Films like Robert Altman’s The Long Goodbye and Jim McBride’s Breathless anticipate Tarantino’s sardonic contemporary pop-pulp fusion, and share Los Angeles/Hollywood coordinates and drug-culture comic elements. But unlike either Altman or McBride, Tarantino ultimately redeems genre morally; even in Reservoir Dogs’ world of simulation and identity-projection, betrayal is still betrayal. Pulp Fiction attaches scant irony to the conceit of a professional killer’s spiritual conversion and renunciation of crime.

Far from succumbing to easy cynicism, Tarantino achieves the remarkable feat of remaining a genre purist even as his films critique, embarrass, and crossbreed genre. Like the critics-turned-directors named above, Tarantino can’t or won’t entirely go native; instead he retains both the sensibility of the profound cinephile and a palpable, almost innocent faith in cinema, a movie idealism that frees him to approach writing and directing on one level as an almost intoxicating play of formal and grammatical adventures and inversions and reinventions of code.

In Pulp Fiction, one such excursion is the sequence at Jackrabbit Slims’, a restaurant/club that inverts the archetypal waitress-to-superstar legend by using lookalikes to reduce dead ’50s idols (Monroe, Dean, etc.) to table staff; the menu meanwhile collapses film history into pure consumption, offering Douglas Sirk steaks and Martin & Lewis shakes (junk food is a Tarantino motif). Vincent Vega (John Travolta) escorts his boss’s girl Mia (Uma Thurman) to this pop mausoleum, and the two connect. The scene unexpectedly achieves a kind of abandon that reminds me of Leos Carax: Mia and Vincent pairing for a cool, beyond-chic twist on the restaurant’s dancefloor, their ultrastylized choreography the very image of the genre rhetoric of attitude, manners, and gesture that Tarantino seems to thrive on. He finds a Juliette Binoche in Uma Thurman here—and in the next scene as she dances alone in her house: it’s an almost transcendent moment.

Tarantino’s semi-mischievous reclassification of the crime movie as art film, begun in Reservoir Dogs and carried through in Pulp Fiction, is accomplished partly through the introduction of improbably elaborate narrative architecture that obliges the viewer to contemplate the usually invisible mechanisms of narrative selection. But more crucially, in Tarantino’s oeuvre, spectacle and action paradoxically take the form of dialogue and monologue. The verbal setpiece takes precedence over the action setpiece, particularly in Reservoir Dogs, where, after all, the film’s central, defining absence is the much-discussed but never-shown jewelry store holdup. As Mr. Orange’s carefully rehearsed and Method-acting-perfected anecdote about a drug deal and a men’s room full of cops demonstrates, truth, even reality, become merely verbal constructs. More than what they do, what the characters say—and they never stop talking—guarantees their existence.

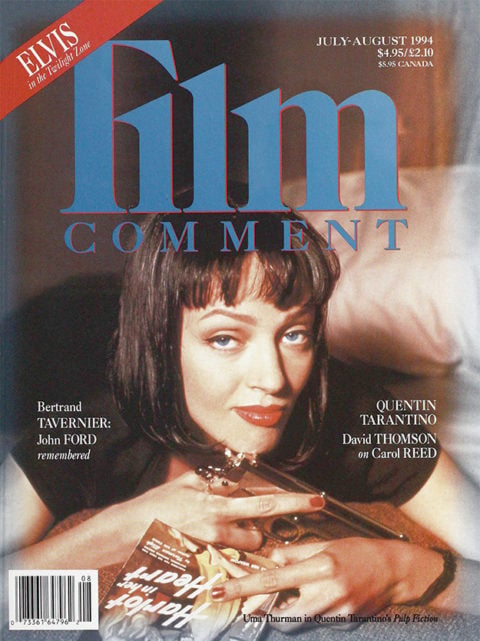

Pulp Fiction (Quentin Tarantino, 1994)

Both Pulp Fiction and Reservoir Dogs push genre convention towards dissonance, not only by saturating them in pop self-referentiality, but by staging philosophical and metaphysical questions latent in genre itself. Reservoir Dogs confronts crisis of meaning and the limits of the knowable, from the opening argument about Mr. Brown (Quentin Tarantino)’s reading of Madonna’s song “Like a Virgin,” to undercover cop Mr. Orange’s deceptive text (does that make him a sub-tec?), to the final negation of meaning faced by the betrayed Mr. White, who, falling dead, leaves an empty frame to express final, definitive denial of meaning’s presence. But if Reservoir Dogs implies truth and fiction alike are acts of both will and faith, in Pulp Fiction verbal and narrative monopoly over truth shows signs of breaking down. Now there are three interdependent stories, far less determinist in character and not imperiled by Dogs’ narrative crisis of confidence; and now the spoken word, though potent, isn’t absolute—as Vincent says of a rumor about Mia, “It’s not a fact, it’s just what I heard.”

Pulp Fiction shares its predecessor’s fetishes—violence as grammar; styling over pathology; plot as farcical, sadistic game; a hermetic, atemporal-yet-retro sense of the present—but is a far more adroit, nuanced work. Its short-story format, complemented by an anthology of period styles from the ’50s, the ’70s, and ’40s noir, liberates its fondly regarded characters from genre’s fatal maze. In place of Reservoir Dogs’ mounting crescendo of confrontations, Pulp Fiction against all expectation resolves its narrative threads with a series of negotiated settlements. The film is rife with amicable partings, terse exchanges of bygones, acts of generosity and forgiveness; all the stories furnish lucky escapes from nightmarish, no-win predicaments. If it’s Tarantino’s Short Cuts, call it Close Shaves.

But Tarantino ventures further. By opting for a structure that scrambles chronology without flashbacks, he grants centrality to the transformation of the character of killer Jules (Sam Jackson), who survives death through “divine intervention,” is blessed and cleansed by Harvey Keitel’s debonair angel, and discovers mercy. Jules is the beneficiary of the film’s accumulated grace, and Tarantino, revising the image of void that ended Reservoir Dogs, frees him to exit the film’s last shot.

Both Pulp Fiction and Reservoir Dogs pull in different aesthetic directions simultaneously—realism on the one hand, artifice on the other.

That’s this mix that I’ve been trying to do. I like movies that mix things up. My favorite sheer cinematic sequences in Pulp Fiction, like the 00 sequence, play like, Oh my God, this is so fucking intense, all right; at the same time, it’s also funny. Half the audience is tittering, the other half is diving under the seat. The torture scene in Reservoir Dogs works that way, too. I get a kick out of doing that. There’s realism and there’s movie-movie-ness. I like them both.

The starting point is, you get these genre characters in these genre situations that you’ve seen before in other movies, but then all of a sudden out of nowhere they’re plunged into real-life rules. For instance, in Reservoir Dogs the fact that the whole movie takes place in real time: what would normally be a ten-minute scene in any other heist movie ever made—all right, we’re making the whole movie about it. That’s not ten minutes, it’s an hour. The movie takes place in the course of an hour. Now, it takes longer than an hour to view it because you go back and see the Mr. Orange story. But every minute for them in the warehouse is a minute for you. They’re subjected to not a movie clock but a real-time clock. So you’ve got these movie guys, they look like genre characters but they’re talking about things that genre characters don’t normally talk about. They have a heartbeat, there’s a human pulse to them.

One of the things that struck me about Reservoir Dogs was that it felt very theatrical in terms of mise-en-scene, especially the section between Steve Buscemi and Harvey Keitel before Michael Madsen arrives, where you film them as if they’re on an empty stage.

That was actually a problem [when] trying to get the film made. People would read it and go, “Well, this isn’t a movie, this is a play, why don’t you try and do it in an Equity Waiver house?” I was like, “No, no, no, trust me, it’ll be cinematic.” I don’t like most film versions of plays, but the reason I had it all take place in that one room was because I figured that would be the easiest way to shoot something. To me, the most important thing was that it be cinematic. Now, having said that, one of the things I get a big kick out of in Reservoir Dogs is that it plays with theatrical elements in a cinematic form—it is contained, the tension isn’t dissipated, it’s supposed to mount, the characters aren’t able to leave, and the whole movie’s definitely performance-driven. Both my films are completely performance-driven, they’re almost cut to the rhythm of performance.

Performance being a key theme in the film—Mr. Orange’s onscreen construction of his fictitious persona obviously suggests that the other characters do much the same thing.

Exactly. That’s a motif that runs through all these gangster guys. Jules [Sam Jackson] has the line in Pulp Fiction, “Let’s get into character.” They’re a cross between criminals and actors and children playing roles. If you ever saw kids playing—three little kids playing Starsky and Hutch interrogating a prisoner—you’ll probably see more real, honest moments happening than you would ever see on that show, because those kids would be so into it. When a kid points his finger at you like it’s a gun, he ain’t screwing around, that’s a gun where he’s coming from.

It was never a conscious decision, playing on the idea of big men are actually little boys with real guns, but it kept coming out and I realized as I was writing Pulp, that actually fits. You can even make the analogy with the scene with Jules and Vincent [John Travolta] at Jimmy [Quentin Tarantino]’s house, they’re afraid of their mom coming home. You spilled shit on the carpet—clean up the mess you made from screwing around before your mom gets home.

Pulp Fiction (Quentin Tarantino, 1994)

The opening scene of Reservoir Dogs with the characters at the diner to me isn’t naturalistic, but rather sets up the illusion of naturalism.

It has that cinéma-vérité give and take, and yet: it has one of the most pronounced camera moves in the whole movie, that slow-moving 360 where people get lost and then you find them again. But while I’ve got this big camera thing happening—and believe me, it was a big pain in the ass to shoot that—at the same time the camera is just catching whoever it happens to catch at the time. It’s not choreographed so that it’s on Mr. Orange and it hits Mr. Pink as he says his line and then finds itself on Mr. Blonde as he says his line—no, it’s not doing that at all, people are talking offscreen and the camera’s just doing its own independent thing.

One of the things I like doing is incorporating many different styles of shooting in the course of making a movie. I never shoot in one specific cinematic language. I like using as many as are appropriate. Part of the fun of that opening sequence is that there’s three different styles of shooting. The whole first part, the Madonna section, is just the camera moving around—even when you go to a closeup, the camera’s still doing its move around. Then when it gets into the Harvey Keitel-Lawrence Tierney thing about the address book, you stop and do two-shots, and then when it gets into the tips part, we’ve got the geography of the table now, so the whole thing is done in these massive closeups. Whenever you do a scene that long, you have it break it down into sections. Ten minutes for your opening sequence is a real long fucking time, especially if they’re doing nothing but sitting down talking. Why did I shoot the third section in closeups? I don’t really have an answer—it just felt right.

So what do you do if it’s ten minutes of one person talking in a room, not moving about?

I kind of do that with the Christopher Walken scene [in Pulp Fiction]. Three pages of monologue, this long story. And I’m not Mr. Coverage. Unless I know I want to shoot a lot of different things so that I can play around with it in the editing room, I shoot one thing specifically and that’s all I get. I never cover myself.

What kind of coverage did you do in the Walken scene?

I shot maybe 13 or 14 takes of the basic shot that you see in the movie, the kid’s point of view. Then I did five or six takes of him doing it in closeup, and then I just had the little kid. Chris would do one take this way and one that way. He’s telling a three-part story about the First World War, the Second World War, and then Vietnam, and all three beats are very different. So I could use the more humorous take on the First World War and then the Second World War story where he’s talking about Wake Island, which is more tragic, I took his darkest take, and then for the Vietnam story I took his most irreverent one, which is the funniest. The whole thing with him is take it and run with it. He’s just so great at doing monologues, about the best guy that there is at it, and that’s why he did the movie, because he doesn’t get the chance to do three-page monologues in movies knowing its not gonna be cut.

One of the fun things about making a movie is, there’s a whole lot of vocabulary, so this scene I’ll shoot in one long take, this scene I want to do through forced perspectives, this scene I want to do with very minimal coverage, like the bathroom scene between Bruce Willis and Maria de Medeiros.

What do you mean, forced perspectives?

The camera’s taking some odd point of view.

For instance, in Reservoir Dogs when you film Buscemi and Keitel in the bathroom from way down the hallway?

Exactly. Or the perspective outside the doorway during the scene between Bruce and Maria, which is set up that way so you feel like you’re a fly on the wall, observing these people alone together acting like people act when they’re alone. The sequence when they’re in the hotel room, it should be somewhat almost uncomfortable and embarrassing being in the room with them because they’re madly in love with each other and they’re at that uppermost honeymoon point of a relationship so they’re talking all this baby talk. You’re watching something you shouldn’t really be seeing, and you don’t know how much you want to see it because there’s an extreme level of intimacy going on. When he first comes in, that whole sequence is just made out of three cuts, three long sections; there’s very little intercutting in the entire motel sequence. And the shower sequence is just one shot. The third section with the big argument about the watch was done with zooms slowly creeping in. Focusing in but not moving: a dolly up to somebody has a whole different feel, a zoom is more analytical. Also, there’s a tension when actors have to pull the scene off in one shot. If you try to get too smart with it, you shoot yourself in the foot, but there’s something about getting together with the actors and saying, “Look, this is the deal, we’re gonna do these-many takes and the best one is gonna be the one in the movie.” Good actors rise to the occasion.

Have you ever been forced to patch a scene or moment together in the cutting room because it didn’t work the way you shot it?

Part of my job if I do something like that is to know I got it when we’re on the set. If you get to the editing room and it absolutely didn’t work, then you’ll still make it work. Sometimes you have a great sequence but with a stumble, and you got to fix that stumble.

Other scenes I know that I’m gonna shoot from a zillion different angles because in the editing room I want to be able to completely pop around and cut to performance. People think you shoot a lot of different angles just because you’re doing action. That’s true, but the thing is, it’s also a big performance thing. When you look at the way Tony Scott did the Christopher Walken-Dennis Hopper scene in True Romance, a million different angles, but it’s all cut to a performance rhythm.

I tend to associate that kind of coverage with a lack of directorial point of view.

When Tony does it, it’s not a willy nilly thing, that’s just how he shoots. His whole style is to have a cut every 15 seconds.

Can’t stand that.

Yeah, but when you say you can’t stand that, you’re reacting against his aesthetic—but that’s what he wants to do. Me, I like to hold for as long as I can before I have to cut, and then when I do cut, I want it to fucking mean something. At the same time, I love how Tony does it. The whole sequence in Pulp Fiction where Sam Jackson and John Travolta come to the yuppies’ apartment is covered in that style, because I’m dealing with Sam’s big monologue and I’ve got all these guys all over the room. We’re popping all around.

Was that the most covered scene in the film?

That and the whole [coffee shop] sequence at the end is covered from this side and that side so that I can pretty much cross the line at will, depending on the action. Far and away, forget what anyone else says, the biggest problem with making movies is that fucking axis line. I always thought that would be a major fucking problem that I would have, because I never quite understood it; if you tried to explain it to me, after a certain point I would glaze over. I realized that I actually did grasp it, instinctually. In that sequence you start out with the guys here, and I’m coming this way [Sam Jackson left/Tim Roth right], and I want to get over this way [right of Roth], and just as we were shooting I figured out the exact line, the exact setup, and the exact cut that would bring me over here—OK, great! I’ve got a really good script supervisor, and his number one thing is the line. And from the moment that I established that I can cross the line, I know I can go back—I got over there the way you’re supposed to, it’s not crossing the line, it just gets me over to the other side. And once I got over there, I can go back and forth between the two. I figured that out on my feet, and it’s one of my prouder moments.

Pulp Fiction (Quentin Tarantino, 1994)

A moment that really stands out in Reservoir Dogs is the cut to Tim Roth firing the gun at Michael Madsen at the end of the torture scene. It’s one of those cuts that just knocks you out. Is there a secret to a cut like that?

It’s a great emotional cut. Like after all those long takes in Rope, all of a sudden you cut to Jimmy Stewart. They fucked up, they said something wrong, and it cuts to Jimmy Stewart’s reaction, you’ve never seen a reaction shot the whole movie—whoa! I figured out what was important was watching Mr. Orange empty out his gun. It wasn’t BLAM–cut to Michael Madsen—BOOM. More shots. It wasn’t going back and forth between Mr. Blonde getting shot and Mr. Orange shooting. It looks like he’s gonna set the guy on fire and BOOM he’s blown out of frame and we see the guy who you forgot was even in the room, by this time he’s become a piece of furniture. And as he’s emptying the gun, the camera goes around him and reveals Mr. Blonde blown all the way across the warehouse. It was realizing that the visceral dramatic impact of the piece was not Mr. Blonde getting shot but Mr. Orange doing the shooting.

Because it’s Mr. Orange finally doing something. The whole movie he’s lying there and suddenly he acts.

One of the things about Reservoir Dogs that really came off was how after a certain point you just forgot Orange was in the room. You can see him, he’s there, but his presence becomes this lump. It wasn’t like we even cheated by framing him out constantly so you get the illusion of being alone—Blonde actually goes over to him and still he doesn’t make the impression. So when Orange shoots him it’s a real jolt. They’re always referring to him, too—he’s the reason they don’t leave. The whole thing as a writer was to constantly throw something new in their path that they have to deal with too. The trick was to keep them in the warehouse. Why would they stay? When all of this stuff starts becoming clear? Because something new keeps happening. Harvey can’t take him to a hospital but Joe’s supposed to be there, Joe can get a crook doctor like that; all right, if we just sit here and wait for Joe at this rendezvous—that’s what he’s saying to Mr. Orange. The irony is, when Joe shows up, he shows up to kill Orange. Then Mr. Pink shows up and says, “No, this was a setup.” Mr. White never thought of that, now he’s thinking about that. And Mr. Pink is saying, “No one’s showing up, we’re on our own, we gotta do something.”

And Pink and Blonde have no emotional investment in Orange, unlike White.

Oddly enough, though, me and Steve have talked about this quite a bit. People write off Mr. Pink as being this weasely kind of guy who just cares about himself, but that’s actually not the case. Mr. Pink is right throughout the whole fucking movie. Everything he says is right, he just doesn’t have the courage of his own convictions. However, there’s a moment that nobody ever talks about, nobody catches, it’s there but they don’t see it: he says, “Look, Joe ain’t coming, Orange was begging to be dropped off at a hospital. Well, since he doesn’t know anything about us, I say it’s his decision—if he wants to go to a hospital and go to jail afterwards, then that’s fine. That’s better than dying.” So then Mr. White does something different than he’s done throughout the entire movie. His whole thing throughout the whole movie is, What about Orange? What about Orange? But now he says, “Well, he knows a little bit about me.” His one moment of self-interest in the whole movie. If all he gave a shit about was just saving Mr. Orange, he might have kept his mouth shut and taken the consequences. But he says it. And Mr. Pink says, “Well, that’s fucking it. We’re not taking him.” And now it’s not on Mr. White’s shoulders anymore, now Mr. Pink is drawing the line, and they get into a fucking fight about it, White conveniently lets Mr. Pink be the bad guy now and then actually slugs him out of righteous indignation. Faced with that one little moment where he could be completely selfless, White doesn’t rise to the occasion, which in some ways even highlights what he does later on when he actually does rise to the occasion. I never make a big dramatic moment about that. White’s hesitation is very human.

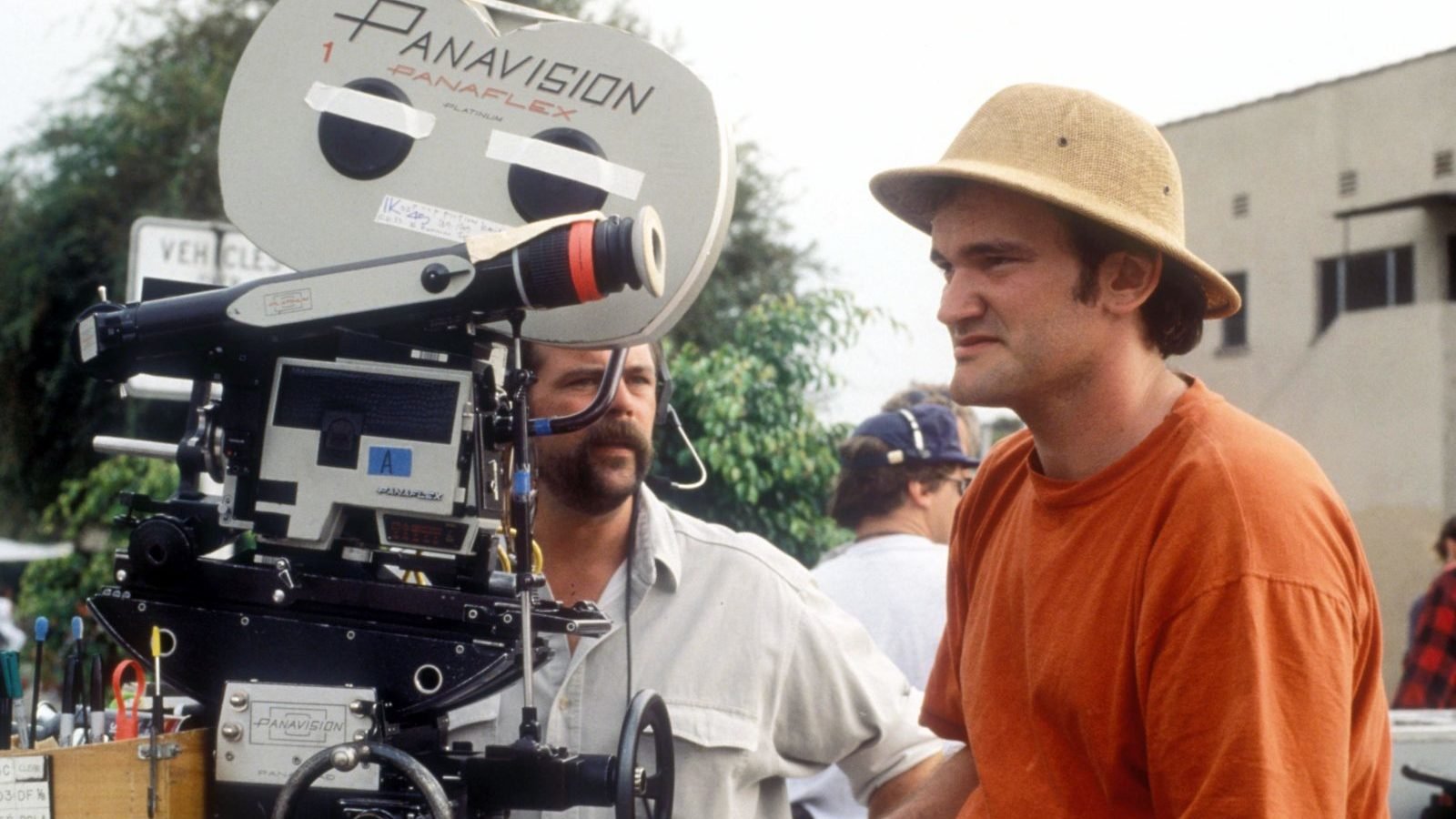

John Travolta and Quentin Tarantino on the set of Pulp Fiction (Quentin Tarantino, 1994)

Jean-Pierre Melville’s films are maybe the primary influence on Reservoir Dogs—I think Le Doulos particularly, with its emphasis on structure and mannerism. Yet there are big differences: Le Doulos is so minimalist and nonverbal, Melville applies a less-is-more principle; Reservoir Dogs is ruled by verbal excess. And Le Doulos has a very steady, even tone, where Reservoir Dogs is all peaks and valleys. I think the relationship is fascinating.

I do, too. Le Doulos has always been probably my favorite screenplay of all time—just from watching the movie. I just loved the wildness of watching a movie that up until the last twenty minutes I didn’t know what the fuck it was I was looking at. And the last twenty minutes explained it all. I was really fascinated by how, even though you don’t have any understanding about what’s going on in that first hour, you’re emotionally caught up in it. I know when I go see a movie and I start getting confused, I’m emotionally disconnected, I check out emotionally. For some reason I don’t in Le Doulos.

The film’s power is that it’s genuinely mysterious.

But the first time you see it you have no idea that mystery is gonna be solved as well as it is. That’s the joy of it—I’ve had faith in this movie all this time and I had no idea my faith was gonna be paid back so well. [Laughs.]

You feel the director at play with the material and with you—that’s the emotional thread, his feeling for the genre.

I think you’ve hit the nail on the head—99 percent of the reason that when a film starts confusing me I check out is because I know it’s not intentional. I know whoever’s at the helm doesn’t have firm control of the material and it’s a mistake that I’m confused. When you know you’re in good hands, you can be confused and it’s okay, because you know you’re being confused for a reason. You know you’ll be taken care of.

Were you concerned about what unified Pulp Fiction as you wrote it?

In a way yes, in a way no. The most organic stuff when you’re writing something like this, taking all these separate pieces and trying to make one big piece out of it, the best, richest stuff you find as you’re doing it, you know? I had a lot of intellectual ideas, like wouldn’t it be great if this character bumped into that character. A lot of it was kind of cool, but if it just worked in a cool, fun, intellectual way, ultimately I ended up not using it. It had to work emotionally.

As opposed to Dogs, which is a complete ensemble piece, [Pulp Fiction] works in a series of couples—everybody’s a couple all the fucking way through. It starts off with Tim Roth and Amanda Plummer, then it goes to Sam Jackson and John Travolta, then John Travolta and Uma Thurman , then it goes to Bruce Willis and the cab driver, then it’s Bruce and Maria de Medeiros and then for a moment after he leaves her he’s the only character in the movie who’s viewed completely alone. Then he makes a bond with this other character and they become a team. It’s only when they become a team that they can do anything. Circumstances make them a couple.

Your characters are all social beings situated in their own private culture. The only other loner is Madsen in Reservoir Dogs. He’s not on the same wavelength as the other guys.

But him and Chris Penn are just as close, if not closer, as the others.

But there’s a side of Madsen that nobody knows about. Nobody really truly knows him.

Even Chris doesn’t know about it. Some switch got flipped in prison.

Pulp Fiction (Quentin Tarantino, 1994)

The screenplay for Pulp Fiction opens with the title “Three stories … about one story.” What does that mean?

I thought I was writing a crime film anthology. What Mario Bava did with the horror film in Black Sabbath I was gonna do with the crime film. Then I got totally involved in the idea of going beyond that, doing what J.D. Salinger did with his Glass family stories where they’re all building up to one story, characters floating in and out. It’s something that novelists can do because they own their characters, they can write a novel and have a lead character from three novels back show up.

That’s why all your films have references to characters from one another. The characters in Reservoir Dogs refer to Marsellus, who is the hub of all the stories in Pulp Fiction.

Very much so, like Alabama. To me they’re all living in side of this one universe.

And it isn’t [pointing out the window] out there.

Well, it’s a little bit out there, and it’s also there, too [points at his TV], in the movies, and it’s also in here [points to his head]. It’s all three. I very much believe in that idea of continuing characters. So what I mean when I wrote “Three stories .. . about one story,” when I finished the script I was so happy because you don’t feel like you’ve seen three stories—and I’ve gone out of my way to make them three stories, with a prologue and an epilogue! They all have a beginning and an end. But you feel like you’ve seen one story about a community of characters, like Nashville or Short Cuts where the stories are secondary. This is a much different approach; the stories are primary, not secondary, but the effect is the same.

I interpreted “Three stories . . . about one story” as being a comment on genre: that these three stories are all ultimately about the genre invoked by the title, Pulp Fiction.

The story of a genre. The three stories in Pulp Fiction are more or less the oldest stories you’ve ever seen: The guy going out with the boss’s wife and he’s not supposed to touch her—that’s in The Cotton Club, Revenge. The middle story, the boxer who’s supposed to throw the fight and doesn’t—that’s about the oldest chestnut there is. The third story is more or less the opening three minutes of Action Jackson, Commando, every other Joel Silve movie—the hitmen show up and blow somebody away. Then they cut to “Warner Bros. Presents” and you have the credit sequence, and then they cut to the hero 300 miles away. But here the killers come in, BLAM-BLAM-BLAM—but we don’t cut away, we stay with them the whole rest of the morning and see what happens to them after that. The whole idea is to have these old chestnuts and go to the moon with them.

You also combine these archetypal movie genre narratives with incidents straight our of pop-contemporary urban legends—the date who ODS or the S&M torture chamber in the basement.

If you talk to anybody who was a heroin addict for any period of time, they all have stories about someone who OD’d, they all have their own version of that story. If you talk to any criminal, they all have their own version more or less of The Bonnie Situation, some weird fucking thing that happened that they had to deal with.

On the one hand you’re making films in which you want the audience emotionally involved, as if it’s “real.” On the other you’re commenting on movies and genre, distancing the viewer from the fiction by breaking the illusion. On one level your movies are fictions, but on another level they’re movie criticism, like Godard’s films.

One hundred percent.

Does your movie consciousness prevent you from doing a movie—

—straight.

Right.

Your way of describing it makes what I’m doing sound so incredibly impressive. That’s one aspect of Godard that I found very liberating—movies commenting on themselves, movies and movie history. To me, Godard did to movies what Bob Dylan did to music: they both revolutionized their forms. There were always movie buffs who understood film and film convention, but now, with the advent of video, almost everybody has become a film expert even though they don’t know it. My mom very rarely went to movies. However, now that there’s video she sees everything that comes out—I mean everything—but on video, six months after the fact. What I feel about the audience—particularly after the Eighties where films got so ritualized, you started seeing the same movie over and over again—intellectually the audience doesn’t know that they know as much as they do. In the first ten minutes of nine out of ten movies—and this applies to a whole lot of the independent films that are released, not the ones that can’t find a release—the movie tells you what kind of movie it’s gonna be. It tells you everything that you basically need to know. And after that, when the movie’s getting ready to make a left turn, the audience starts leaning to the left; when it’s getting ready to make a right turn, the audience moves to the right; when it’s supposed to suck ’em in, they move up close… you just know what’s gonna happen. You don’t know you know, but you know.

Admittedly, there’s a lot of fun in playing against that, fucking up the breadcrumb trail that we don’t even know we’re following, using an audience’s own subconscious preconceptions against them so they actually have a viewing experience, they’re actually involved in the movie. Yeah, I’m interested in doing that just as a storyteller. But the heartbeat of the movie has to be a human heartbeat. Now, if you were to walk out of the theater after the first hour of Pulp Fiction, you really haven’t experienced the movie, because the movie you see an hour later is a much different movie. And the last twenty minutes is much different than that. That’s much harder to do than when you’re dealing the a movie about a ticking bomb like Reservoir Dogs. Pulp Fiction is much more of a tapestry.

Again, a lot of things that seem unusual for films—for instance, the Reservoir Dogs characters’ offhanded brutality, their commitment to their coldbloodedness—are not unusual in a novel in the crime genre. The characters have a commitment to their own identity, as opposed to action movies or big Hollywood movies where every decision is very committee-ized and the whole fear is that at some point the character might not be likable. But people find John Travolta’s character in Pulp Fiction not only likable but very charming— considering the fact that he’s first presented as a hitman and that’s never taken back. He is what he is, he is shown plying his trade but then you get to know him above and beyond that. The reverse of never breaking that hitman mode in Hollywood movies is, Wow, he can’t fucking do that, he can’t kill the villain with his bare hands, why don’t we have him punch him and have the villain fall on something—so then he killed him but he didn’t really mean to so he can go back to his family and everything is cool, we can still feel good about liking him. That kind of bullshit I can’t abide. But you have to be engaged in the character in a human way or else it becomes an intellectual tennis game.

But once a film starts breaking itself down, commenting on itself, exposing the illusions of fiction , you open a Pandora’s Box. When Madsen makes the Lee Marvin joke in Reservoir Dogs or Uma Thurman draws a square out of thin air in Pulp Fiction, once you reposition the viewer like that, can you get away with reverting to straight storytelling later in the film as you seem to?

I think I do. What makes that whole square so exciting is you hadn’t seen anything quite like it in the movie up until that point. There are little moments like that—you see the black-and-white behind Bruce Willis in the cab, the car process shots in general but they never disconnect you emotionally. Because after the square, you dive into one of the more realistic sections of the movie. You go on a fucking date with them, that’s not a quick “They talk—bababababa—and get to the point.” The movie almost stops for you to get to know Mia [Uma Thurman].

But the device of giving genre characters like hitmen unlikely conversational topics inevitably draws attention to the fictive basis of what’s onscreen.

That’s putting your preconceptions about what you think people who do that for a living talk about.

No, on a behavioral, emotional level you’re making choices that go against naturalism. When Sam Jackson has all that business with the hamburger and delivers that long spiel to Frank Whaley in the apartment before killing him, the only naturalistic justification is because his character has some need to do that but you don’t make that choice. So where’s it coming from?

To me, it’s coming from the fact that he’s taking control of the room: you walk in like you’re gonna cut off everybody’s head, but then you don’t cut off their heads. He’s never met these guys before, he’s improvising, he’s gotta get that case. So he’s like a real nice guy, he’s cool, he’s kind of playing good cop/bad cop and he’s the good cop, he’s the guy who sucks you in. He says that speech before he kills him because… that’s what he does. He explains that later in the movie–“I have this speech I give before I kill somebody.” That’s Jules’s thing, to be a badass. It’s a macho thing, and it’s like his good-luck charm. He’s playing a movie character, he’s being the Green Lantern saying his little speech before he does what he does.

That’s what I mean—that’s where it stops being a character and starts being a commentary.

To me, they don’t necessarily break the reality. You hear stories about gangbangers doing routines from movies before they do a drive-by.

Pulp Fiction (Quentin Tarantino, 1994)

Why do you think neither of your films adheres to the classical principle of single-character point of view?

I’ve picked two projects where it’s very organic and almost imperative to do it that way. I keep applying to cinema the same rules that novelists have when they come to writing novels: you can tell it any way you want. It’s not just, You have to tell it linearly. It’s inherent in the stories. Reservoir Dogs and Pulp Fiction would be dramatically less interesting if you told them in a completely linear fashion.

And the True Romance screenplay is linear.

True Romance wasn’t written in a linear fashion originally. It started off with the same first scene of Clarence talking about Elvis, then the next scene was Drexel killing all his cronies and the third scene was Clarence and Alabama at Clarence’s father’s house. And then you learn how he got what he got. Tony made it all linear and it worked that way.

If you break it into three acts, the structure they all worked under was: in the first act the audience really doesn’t understand what’s going on, they’re just getting to know the characters. The characters have far more information than the audience has. By the second act you start catching up and get even with the characters and then in the third act you now know far more than the characters know, you’re way ahead of the characters. That was the structure True Romance was based on and you can totally apply that to Reservoir Dogs. In the first section, up until Mr. Orange shoots Mr. Blonde, the characters have far more information about what’s going on than you have—and they have conflicting information. Then the Mr. Orange sequence happens and that’s a great leveler. You start getting caught up with exactly what’s going on, and in the third part when you go back into the warehouse for the climax you are totally ahead of everybody—you know far more than anyone of the characters. You know more than Keitel, Buscemi, and Penn because you know that Mr. Orange is a cop and you know more than Mr. Orange does because he’s got his own little ruse he’s gonna say but you know Mr. Blonde’s lineage, you know he went to jail for three years for Cris Penn’s father, you know what Chris Penn knows. And when Mr. White is pointing the gun at Joe [Lawrence Tierney] and saying, “You’re wrong about this man”—you know he’s right. You know Keitel’s wrong, he’s defending a guy who’s actually selling him out.

To me, 90 percent of the problem with movies nowadays lies in the script. Storytelling has become a lost art. There is no storytelling, there’s just situations. Very rarely are you told a story. A story isn’t “Royal Canadian Mounted Police officer goes to New York to capture a Canuck bad guy.” Or, “White cop and black cop looking for a killer but this time they’re looking in Tijuana.” Those are situations. They can be fun. I just saw Speed the other day, a totally fun movie, had a blast. The last twenty minutes gets kind of cheesy, but up until then it was totally engaging. Situation filmmaking at its best, because they really went with it. Speed works. Most of them don’t work. The only thing is, I used to ride a bus for a year and I know that people aren’t as gabby on a bus as they’re portrayed. They were kind of doing an Airport thing. But on a bus you’re getting to work and people do not talk.

I watched Macon County Line again a few months ago. Cool film. And I was shocked at how much of a story it told. Not that complicated a story, but it took me to different levels in the course of the story. One False Move was a story; they didn’t tell you a situation, they told you a story. However, Groundhog Day is one of my favorite movies of last year, if not my favorite, and that’s a totally situation movie, but they went way beyond the situation and told a story. A friend of mine said action movies are the heavy metal of cinema, and that’s not that far off. Action movies have become the mainstay for young male cinemagoers, and they don’t have the Good Housekeeping Seal of Approval. However, you’re so used to seeing weak-assed action films that don’t deliver. Even a mediocre action movie has a couple of good sequences that you can enjoy to some degree while you’re watching, but then it’s gone by the next day. Speed stayed with me. I’m kind of interested in seeing it again. What other action movies have you seen recently that you look forward to seeing again?

Fox approached me for Speed. I didn’t read it, my agent didn’t give it to me because I was doing Pulp Fiction. I was sent a script this weekend that’s gonna be a big movie and they want me. lt was an interesting idea. I don’t read many scripts but I read this one. And it’s a fun movie. I’ll see it on opening night. But it’s not what I want to spend a year making. And it’s an action movie, wall-to-wall action scenes. And I don’t do wall-to-wall action movies.

Do you think Pulp Fiction represents the start of a partial retreat from genre?

The entire time I was writing Pulp Fiction I was thinking, This will be my Get-it-Out-of-Your-System movie. This will be the movie where I say goodbye to the gangster genre for a while, because I don’t want to be the next Don Siegel—not that I’m as good. I don’t want to just be the gun guy. There’s other genres that I’d like to do: comedies, Westerns, war films.

Do you think your next film might not even be a genre film?

I think every movie is a genre movie. A John Cassavetes movie is a genre movie—it’s a John Cassavetes Movie. That’s a genre in and of itself. Eric Rohmer movies to me are a genre. The thing that I came up with a little bit after that was, If you come up with something that falls into that same crime/mystery genre and it’s really pure and really organic and it’s what you should do, well, if you really want to do it, do it. Because I’m basically lazy, and to get me to stop enjoying living life it’s gotta be something that I really wanna do. I’m gonna take almost a year off. I remember when I was younger I was, like, I want to be like Fassbinder, 42 films in ten years. Now that I’ve made a couple, I don’t want it.