Playing Along: Deep in the Forest

It’s quite possible that you heard a snatch of “Falling” in your head when you read the words “Twin Peaks”: the spare, four-note, Duane Eddy–influenced bass hook followed by a response from a Rhodes piano, over and over, their back-and-forth in time lost beneath an ascending swell of swirling synthesized strings. It’s a sound that, once heard, isn’t forgotten.

That sound will likely return once more this May, when Mark Frost and David Lynch’s Twin Peaks saga resumes a quarter-century after it was last heard in the spin-off film Twin Peaks: Fire Walk with Me. Predating the “quality television” PR revolution by about a decade, Twin Peaks has remained in the public consciousness after the so-called Golden Age has come and gone, with a persistence that defies generational boundaries. My grandmother was an avid viewer from the moment that it first aired in April 1990, maybe because the supernatural elements reminded her of another ABC network cult item, Kolchak: The Night Stalker (1974-75), and many of the series’s most avid enthusiasts weren’t even born when the show ended its 30-episode run in June of ’91.

The longevity of Twin Peaks would be remarkable under any circumstances, and is even more so because the show fails to meet most of the criteria by which hour-long dramas are usually judged to be Great. Its sense of character development isn’t a patch on, say, what you’d find on L.A. Law (1986-94), which no one is rushing to revive; and it exhibits very little of the grand narrative architectonics that we’re told have elevated serial TV to the level of Dickens and Dostoevsky. Its two seasons feel instead like a constant high-wire improvisation, sometimes inspired, sometimes not—everyone has their favorite bad Twin Peaks plotline, from the Pine Weasel to Ben Horne’s Civil War reenactments to Nadine’s super-strength.

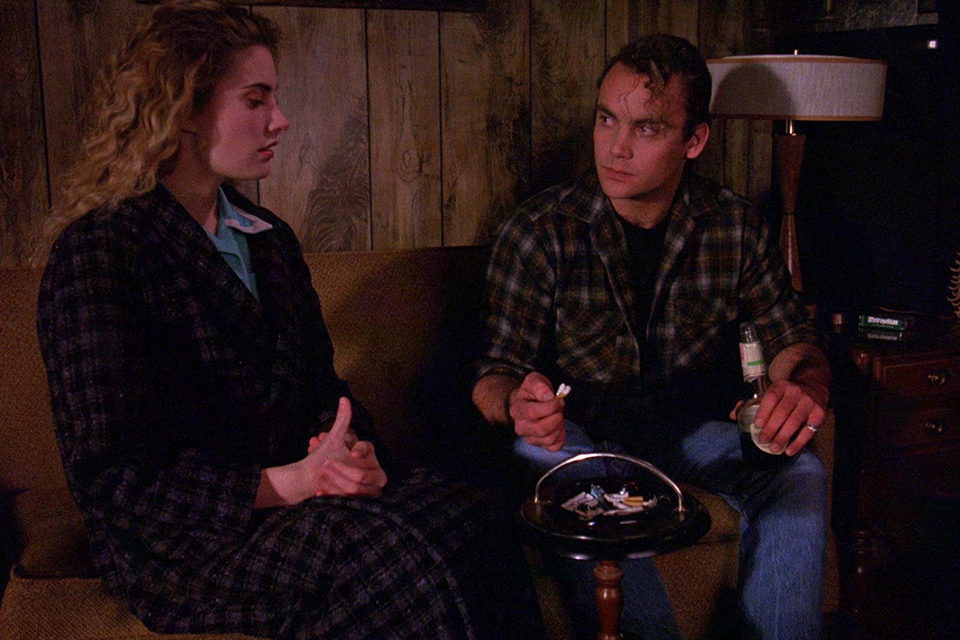

None of this has succeeded in significantly marring the series’s legacy, because what Twin Peaks has in scads is texture. That texture is found in actual tactile materials that make up the show’s world—plaid, leatherette, unfinished wood—and it is found in its tone, its sound, specifically the music by Angelo Badalamenti, which corresponds in some respects to contemporary developments in rock music. This sonic texture is a large part of what makes Twin Peaks, Washington, an alluring and infinitely revisitable place.

“Falling” is an instrumental version of a track which had first appeared with vocals by Julee Cruise on her 1989 album Floating into the Night, co-written and co-produced by Lynch and Badalamenti, continuing a collaboration that had begun with 1986’s Blue Velvet. Badalamenti was nearly 50 when he first came to work with Lynch, and nothing on his résumé to date suggested he was destined for greatness in film scoring when he was brought on to coach Isabella Rossellini in her performance of the title track by producer Fred Caruso—perhaps because it was believed that the Bensonhurst-Sicilian Badalamenti would have some blood- kinship with the roots of doo-wop and 1950s music. Cruise came on board after Lynch’s plans to use the cover of Tim Buckley’s “Song to the Siren” recorded by This Mortal Coil on their 1984 album It’ll End in Tears was rendered impracticable by a $50,000 licensing fee. Instead he recruited Badalamenti to do something that approximated the same mood, and Cruise, who had performed in a musical that Badalamenti had written called The Boys in the Live Country Band in New York, was brought in to provide the vocals. Lynch’s response to the result, Badalamenti would later recall, was “Love at first sound.”

Lynch would finally get his chance to use “Song to the Siren,” laid over a blissed-out coupling between Patricia Arquette and Balthazar Getty in Lost Highway (1997), but it’s worth thinking about the impression that its sound made more than a decade prior, at a crucial point in the filmmaker’s career. This Mortal Coil was a supergroup of sorts, curated by Ivo Watts-Russell, co-founder and presiding genius at London-based record label 4AD, who had become known through the early 1980s for cultivating a roster of artists who specialized in atmospheric dreamscapes. (These extended to the distinctive visual identity of 4AD’s physical albums, courtesy of house designer Vaughan Oliver, who would later help to design the sleeve of Lynch’s 2011 album Crazy Clown Time.) You can locate that “Falling” bass sound in This Mortal Coil’s cover of “Kangaroo,” though any discussion of influence here must be two-sided. The pull of Eraserhead (1977) on an entire generation of arty kids coming into their own in the early 1980s is inestimable, and that film’s “In Heaven” track was covered by 4AD signees the Pixies and Bauhaus, while “Falling” would be recorded by The Wedding Present in 1992, and there’s something positively Lynchian in the yawning open space of Yo La Tengo’s 1993 “Big Day Coming.”

Performers on It’ll End in Tears included members of Dead Can Dance; Howard Devoto, late of the Buzzcocks; and, singing on “Song to the Siren,” Elizabeth Fraser from the Scottish band the Cocteau Twins, an outfit whose practice was every bit as gnomic and interpretation-resistant as Lynch’s. Stung by early criticism of her lyrics, Fraser had taken to singing in a breathy, swirling glossolalia, while guitarist Robin Guthrie’s signature reverb-drenched delay flicker, looking back to the work of Brian Eno, was also one of the principal influences on an emerging group of mostly Anglo-American bands who would be grouped together under the tag “shoegaze.”

What the Cocteau Twins and the shoegaze artists were doing in pop music, Lynch and Badalamenti did contemporaneously in the audiovisual art beamed into people’s living rooms. The unifying elements here are echo and reverb, with their capacity to create the impression of vast, open chambers and a rich, plush romanticism. It was the plaintive, long-ing sound that Lynch loved in his 1950s youth—think of that Duane Eddy twang or Lynch’s beloved Roy Orbison—and that he loved just as much when rediscovered in “Song to the Siren,” or when applied to James Hurley’s falsetto performance of “Just You,” over a silvery guitar line, in Twin Peaks. It’s a sound that can be enormous and oceanic, and for synesthetic images to accompany it you could do worse than the moment when Henry and his neighbor submerge into a bed of milky liquid in Eraserhead, or any number of Lynch’s whirling voids.

The Twin Peaks aesthetic, like that of Blue Velvet, had a great deal to do with ’50s Americana rendered as it resounded across the space of years. A work of warped nostalgia, it was also rather timely; there was some serendipity in the fact that the series laid its scene in Washington State shortly before the eyes of the nation—or at least of the nation’s A&R men—were focused on the Pacific Northwest as they rarely have been before or since. A few months after the series finale, Nirvana’s Nevermind was released, and the thrift store uniform of saddle shoes and cardigans that spread in its wake was familiar to any Twin Peaks viewer.

“Falling,” it should be noted, isn’t representative of the overall style of Badalamenti’s soundtrack work on Twin Peaks, which in fact lacks a single overall style. The Lynch-directed pilot rolls out an eclectic mix that includes finger-snaps and jazzy walking basslines, the midway organ-like tootling that follows mischievous Audrey Horne sabotaging her father’s business, and “Laura Palmer’s Theme,” with its low, steady synth brood breaking into tinkling soap operatic heights, darkly blooming time and again as news of Laura Palmer’s death spreads. What’s most re-markable in rewatching the show’s pilot is just how much music suffuses the thing, accompanying the frequent and often violent displays of emotion—and even before collaborating with Badalamenti, Lynch was creating dense, ultra-detailed ambient environments with sound designer Alan Splet. It is, I suspect, Twin Peaks’s expanse of feeling, the sheer magnitude of emotion, carried on the back of a huge, cavernous sound, that gives the series a unique shelf life even in the age of flash-in-the-pan serial “obsessions” which often make their own attempts at signature sounds. (Remember Making a Murderer? True Detective? Literally any Marvel Netflix series? Of course you don’t.) It’s a sound that can be traced back to “Song to the Siren” and This Mortal Coil and the encounter between the man who has filmed weeping more beautifully than any living director and the man who produced an album called It’ll End in Tears.

Closer Look: The new Twin Peaks series premieres May 21 on Showtime.

Nick Pinkerton is a regular contributor to Film Comment and a member of the New York Film Critics Circle.