Playing Along: Leonard Rosenman (Edge of the City, 1957)

The Dutch-angled scores of Leonard Rosenman make for an ideal sound-track to the sweaty, jittery filmmaking of some 1950s Hollywood. The speed of Rosenman’s notes—first a leisurely gait, then lush and slow, then six climaxes in a row—helped express that all is not right in the worlds of Vincente Minnelli, Elia Kazan, and Nicholas Ray. In the aesthetic systems of panic scored by Rosenman, the act of walking or thinking is turned up several decibels, aided in no small part by the directors’ penchant for overwhelming colors and brash Method-style acting.

The largest influence on Rosenman’s style was the 20th-century composer Arnold Schönberg, with whom he took many musical lessons in 1951, the year of Schönberg’s death. Rosenman was enamored of his 12-tone technique, which treats all 12 notes of the chromatic scale with equal importance. The music never settles into a key for long, so, to the listener, the music sounds jarring and “atonal” (a term Schönberg detested for its lack of specificity). Rosenman took these ideas, which rejiggered the ear’s entire relationship with scale and harmony, and introduced them into edgy Hollywood pictures like East of Eden, The Cobweb, Rebel Without a Cause, Edge of the City, The Rise and Fall of Legs Diamond, The Chapman Report, Fantastic Voyage, and Countdown.

Though Rosenman was recognized with two back-to-back Oscars in the 1970s, the awards were pointedly and ironically not for original compositions but for arrangements of preexisting ones: the classical mix of Handel, Schubert, and Bach in Kubrick’s Barry Lyndon (1975) and Woody Guthrie’s ballads in Hal Ashby’s Bound for Glory (1976). Accepting his Oscar for the Ashby film, Rosenman said with a rueful on-stage huff, “This really is on the borderline of absurdity, because I do write original music, too.” Indeed, Rosenman’s scores charted a new path of tonal sense. Keeping his mentor Schönberg’s legacy alive and well in the Hollywood film, Rosenman restructured the old canons of tonality that seemed limiting and even unsatisfying in the 1950s.

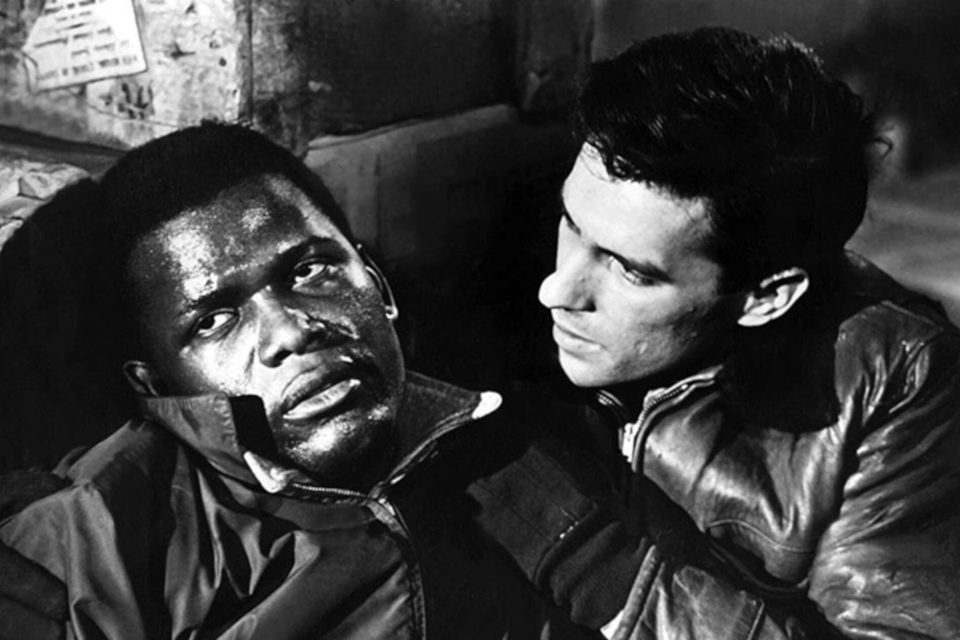

A typical Rosenman job is well illustrated in Martin Ritt’s tough Edge of the City (1957), in which his sounds complement the shy-guy performance of John Cassavetes. In Ritt’s grittier, race-centered offspring of Kazan’s On the Waterfront, Cassavetes plays Axel Nordmann, a sensitive longshoreman whose identity as an army deserter has been discovered by both his white bullying boss (Jack Warden) and his black best friend (Sidney Poitier). When his identity is exposed, we see proto-Shadows shots of Cassavetes walking around a loud New York City in a dazed, nervous silence. Over these images, we hear a viciously self-involved yet tightly controlled cacophony. Clumped-together piano chords clod up and down the keyboard, advancing without any evident chartered path to guide them. The music climaxes about three times in 10 seconds—then, suddenly, the main theme of the picture (a square reverie) is surreally looped back into the crowded soundscape. Rosenman seems hell-bent on denying Axel’s theme the opportunity it may have had to become a solid pop-chart single gussied up by strings à la Percy Faith.

For Cassavetes’ character—a mama’s boy who was dropped from small-town Gary, Indiana, into the punishingly vast metropolis—the Rosenman score serves as the muck of the city he has made his home, his inner urban anxieties given sonic life, unable to be normalized or hushed. It is his alienation from the modern city, it is his confusion at the de facto racism that separates black workers from white—a division that Axel cannot rationalize, complicit as he is by virtue of his white skin, yet he’s unable to say why.

It’s no coincidence that any scene involving conflict with Poitier uses the Rosenman scramble. It’s not Warden’s discovery of Cassavetes’ identity that sets off Rosenman’s horns—it’s Poitier’s. Rosenman’s cues always follow panic within the characters, and nothing gets them more on edge than an interracial friendship (near-romance, really) between a black and a white man.

Edge of the City

In the film’s climactic scene, a fight with hooks between Warden’s Charlie and Poitier’s Tommy, a series of balance-toppling, bouncy timpani rolls and strings arrested in mid-flight, unable to complete a simple phrase, magnify the tragic and senseless spectacle of a black man forced to stick up for his white best friend—and losing his life in the process. In the middle of the fight, Tommy gains the upper hand on Charlie, stamping a foot over his opponent’s hook and waving his own hook in Charlie’s face. “Charlie… Charlie… this doesn’t make sense,” Tommy says with tortured desperation, knowing that all the dockworkers and, by way of Rosenman’s bloodthirsty piccolo trumpet, the whole world is watching, waiting (almost goading him on) to see what he, the black man, will do. Tommy, in trying to rationalize the irrational ubiquity of racism, waits too long and gets his hook caught in a chain-link fence, and as the Rosenman horns reach the apex of their frenzy, Charlie hooks Tommy in the back. The next shrill pierce we hear is not Rosenman’s, but Tommy’s—a bloodcurdling scream at a higher pitch than the last sounded Rosenman horn, blending into Rosenman’s frenzy and working as the brutal last note.

One can’t think of the remarkable Edge of the City without remembering Rosenman’s profound contributions. Though the film’s score does have its fair share of incidental music that could have been written by any composer (jazzy mood music or a generic Latin cha-cha without the Henry Mancini sparkle), Rosenman is not there to simply dress up Ritt’s plain visuals. He intertwines music and image, such that the two cannot be separated. Rosenman himself theorized his own method of composition as a means of revealing the “supra reality” of a situation—that is, the cinematic truth established through the music, not through the visuals, yet ultimately indistinguishable from what’s being shown. In Rosenman’s words, “The music interacts with the intrinsic meaning of the sequence, as distinct from a surface-level meaning . . . You will be particularly aware of the music in such instances, because it tells you something that will make an appreciable difference in your perception of the overall event.”

The music of the “supra reality” is not overlaid, it is interwoven. Think, for instance, of the second movement of Schubert’s Piano Trio No. 2—arranged by Rosenman—in Kubrick’s Barry Lyndon. The regal sparkle of the piano’s march is inseparable from the seduction of Lady Lyndon by Redmond Barry. It hardly matters that the piece had been written more than a century earlier as part of a larger composition; once one has seen Barry Lyndon, one can’t listen to the Schubert without thinking of Ryan O’Neal’s march to Marisa Berenson in the moonlight.

How can a unique image meet a unique musical phrase and sync together, such that one is unthinkable without the other? As a counterexample, most of the themes in Bernard Herrmann’s vast catalog (including the Hitchcock scores, the woozy “Betsy’s Theme” from Taxi Driver, and his devastating “The Road” from Truffaut’s Fahrenheit 451) have lives of their own. Whether a main theme or a 60-second cue, or whether or not they’re under the direction of auteurs with strong voices like Welles, Hitchcock, or Scorsese, Herrmann’s pieces are self-sustaining. They conjure up moods so evocative that they can function as entire worlds separate from the images. Rosenman differs. His dissonant orchestrations work best not by themselves, but when catalyzed by the inspired imagery of his directors and their films’ stars: Richard Fleischer’s sci-fi phantasmagoria, James Dean’s lashing out within Kazan’s CinemaScope arena, Minnelli’s MGM opulence. (In Minnelli’s 1955 The Cobweb, the first Hollywood score totally dependent upon Schönbergian serialism, Rosenman found the most potent chamber for his Wall of Panic.)

In Edge of the City, when Rosenman’s horns go into their frenzied runs, they are not really capturing the emotion of Axel Nordmann, longshoreman and U.S. army deserter; or even of Cassavetes, revolutionary artist soon to break out; but of all who have tried to plaster their personas over in calm tones, not realizing that a terror is radiating outward.

Carlos Valladares has written for The San Francisco Chronicle. He lives in New York City.