Interview: Pier Paolo Pasolini

I have been wondering what I should ask you. Often I ask questions of directors that seem a little stupid, you see, but I don’t want to avoid those, for finally the stupid questions are the ones to which I most want reply. I know that it will be difficult—I don’t think I would be able to answer very well concerning my own films—but I hope that your replies help me to arrive at certain conclusions later. Have you understood?

Yes, I understand.

You know I’m compiling a book on the directing of the non-actor. I am meeting many directors. The book is primarily a way for me to organize my own thinking and to take advantage of the experiences of other directors in order to see how I may be able to create more completely a kind of human existence in front of the camera, without the use of professional actors, and without falling into cinema conventions. The ideas I’m looking for have been discreetly developing for 20 years. So that’s why I’m writing this book, to clarify my ideas. Have you understood?

Yes, very well.

Let me start with a question that may seem stupid—how do you create? Are you aware—even vaguely—of certain recurring processes? What helps you? What pushes you to create? When you want to work, what steps do you take to get started?

What is it that urges me to create. As far as film is concerned, there is no difference between film and literature and poetry—there is this same feeling that I have never gone into deeply. I began to write poetry when I was seven years old, and what it was that made me write poetry at the age of seven I have never understood. Perhaps it was the urge to express oneself and the urge to bear witness of the world and to partake in or to create an action in which we are involved, to engage oneself in that act.Putting the question in that manner forces me to give you a vaguely spiritualistic answer . . . a bit irrational. It makes me feel a bit on the defensive.

Some artists collect information on a subject, like journalists. Do you do this?

Yes, there is this aspect, the documentary element. A naturalistic writer documents himself through his production. Because my writing, as Roland Barthes would say, contains naturalistic elements, it is evident therefore that it contains a great interest in living and documentary events. In my writing there are deliberate elements of a naturalistic type of realism and therefore the love for real things . . . a fusion of traditional academic elements and of contemporary literary movements.

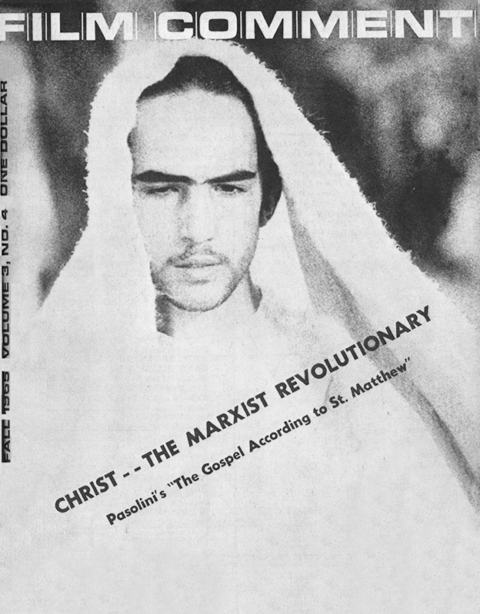

What brought you to The Gospel According to St. Matthew, and once you had the idea, how did you start work on it? Why did you want to do it?

I recognized the desire to make The Gospel from a feeling I had. I opened the Bible by chance and began to read the first pages, the first lines of St. Matthew’s Gospel, and the idea of making a film of it came to me. It’s evident that this is a feeling, an impulse that is not clearly definable. Mulling over this feeling, this impulse, this irrational movement or experience, all my story began to become clear to me as well as my entire literary career.

Once you had this feeling, what did you look for to give it form, to make the feeling concrete?

I discovered first of all that there is an old latent religious streak in my poetry. I remember lines of poetry I wrote when I was 18 or 19 years old, and they were of a religious nature. I realized, too, that much of my Marxism has a foundation that is irrational and mystical and religious. But the sum total of my psychological constitution tends to make me see things not from the lyrical-documentary point of view but rather from an epic point of view. There is something epic in my view of the world. And I suddenly had the idea of doing The Gospel, which would be a tale that can be defined metrically as Epic-lyric.

Although St. Matthew wrote without metrics, he would have the rhythm of epic and lyric production. And for this reason, I have renounced in the film any kind of realistic and naturalistic reconstruction. I completely abandoned any kind of archaeology and philology, which nevertheless interest me in themselves. I didn’t want to make an historical reconstruction. I preferred to leave things in their religious state, that is, their mythical state. Epic-mythic.

Not desiring to reconstruct settings that were not philosophically exact—reconstructed on a sound stage by scene designers and technicians—and furthermore not wanting to reconstruct the ancient Jews, I was obliged to find everything—the characters and the ambiance—in reality. And so the rule that dominated the making of the film was the rule of analogy. That is, I found settings that were not reconstructions but that were analogous to ancient Palestine. The characters, too—I didn’t reconstruct characters but tried to find individuals who were analogous. I was obliged to scour southern Italy, because I realized that the pre-industrial agricultural world, the still feudal area of southern Italy, was the historical setting analogous to ancient Palestine. One by one I found the settings that I needed for The Gospel. I took these Italian settings and used them to represent the originals. I took the city of Matera, and without changing it in any way, I used it to represent the ancient city of Jerusalem. Or the little caverns of the village between Lucania and Puglia are used exactly as they were, without any modifications, to represent Bethlehem. And I did the same thing for the characters. The chorus of background characters I chose from the faces of the peasants of Lucania and Puglia and Calabria.

How did you work with these non-actors to integrate them into a story that was not their own, although analogous to their own?

I didn’t do anything. I didn’t tell them anything. In fact, I didn’t even tell them precisely what characters they were playing. Because I never chose an actor as an interpreter. I always chose an actor for what he is. That is, I never asked anyone to transform himself into anything other than what he is.

Naturally, things were a little more difficult with regard to the main actors. For example, the fellow who played Christ was a student from Barcelona. Except for telling him that he was playing the part of Christ, that’s all I said. I never gave him any kind of preliminary speech. I never told him to transform himself into something else, to interpret, to feel that he was Christ. I always told him to be just what he was. I chose him because he was what he was, and I never for one moment wanted him to be anyone else other than what he was—that’s why I chose him.

But to make your Spanish student move, breathe, speak, perform necessary actions—how did you obtain what you wished without telling him something?

Let me explain. It happened that in making The Gospel, the footage of the characters told me almost always the truth in a very dramatic fashion—that is, I had to cut a lot of scenes from The Gospel because I couldn’t “mystify” them. They rang false. I don’t know what it is, but the eye of the camera always manages to express the interior of a character. This interior essence can be masked through the ability of a professional actor, or it can be “mystified” through the ability of the director by means of cutting and divers tricks. In The Gospel I was never able to do this. What I mean to say is that the photogram or the image on the film filters through what that man is—in his true reality, as he is in life.

It is possible at times in movies that a man who is devious and shady can play the part of one who is naïve an ingenuous. For example, I could have taken a professional and given him the part of one of the three magi—an unimportant part—and by the way it is clear that there is a deep candor in the souls of the three magi. But I didn’t use professionals, and therefore I couldn’t have their ability to transform themselves in to others. I used real human beings, and so I made a mistake and misjudged a man psychologically. My error was immediately evident in the photographed image. There is another rather unpleasant example that has sprung to mind—for the two actors who played those possessed by the Devil, I chose actors from the Centro Sperimentale film school in Rome. I chose them in a hurry. Later, I had to cut the scene because I was obvious that they were two actors from the Centro Sperimentale.

In reality, my method consists simply of being sincere, honest, penetrating, precise in choosing men who psychological essence is real and genuine. Once I’ve chosen them, then my work is immensely simplified. I don’t have to do with them what I have to do with professional actors: tell them what they have to do and what they haven’t to do and the sort of people they are supposed to represent and so forth. I simply tell them to say these words in a certain frame of mind and that’s all. And they say them.

To get back to Christ, once I had chosen the person whose essence or interior was more or less that needed to play the part of Christ, I never obliged him to do any specific things. My suggestions were made one by one, instance by instance, moment by moment, scene by scene, action by action. I said to him, “do this” and “get angry.” I didn’t even tell him how. I simply said, “you’re getting angry,” and he got angry in the way he usually got angry and I didn’t intervene in any way.

My work is facilitated by the fact that I never shoot entire scenes. Being a “non-professional” director I’ve always had to “invent” a technique that consists of shooting only a very brief bit at one time. Always in little bits—I never shoot a scene continuously. And so even if I’m using a non-actor lacking the technique of an actor, he’s able to sustain the part—the illusion—because the takes are so brief. And if he doesn’t have the technical ability of an actor, at least he doesn’t get lost, he doesn’t freeze up.

Although I was able to find characters analogous to the wise men or to an angel or to Saint Joseph, it was extremely difficult to find a character analogous to Jesus Christ. And so I had to be content with finding someone who at least came close to resembling Christ externally and interiorly, but actually I had to construct Christ in the cutting room.

Although other directors make tests, I never make them. I had to make one for Christ, though—not for myself—but for the producer who wanted a certain guarantee. When I choose actors, instinctively I choose someone who knows how to act. It’s a kind of instinct that so far hasn’t betrayed me except in very minor and very special cases. So far I’ve chosen Franco Citti for Accattone and Ettore Garofolo for the boy in Mamma Roma. In La Ricotta, a young boy from the slums of Rome. I’ve always guessed right, that from the very moment in which I chose the face that seemed to me exact for the character, instinctively he reveals himself a potential actor. When I choose non-actors, I choose potential actors.

Naturally, Christ was a more difficult thing for me than Franco Citti because Franco, after all, was to play a part that was more or less himself. First of all, this young Spanish student at the beginning was inhibited about playing the part of Christ—he wasn’t even a believer. And so the first problem was that I had playing Christ a fellow who didn’t even believe in Christ. Naturally this cause inhibitions. This young student wasn’t an extrovert or a simple, normal type of person. He was psychologically very complex, and for this reason it was difficult the first few days to get him to win out over his timidity, his restraint, his inhibitions, while for the other actors I didn’t have this problem. The very minute I put them in front of the camera, they acted the way I wanted them to.

What did you do with your Spanish non-believing non-actor to get the results you wanted?

Nothing really. I simply appealed to his good will. He was a very intelligent and a very cultured young man who became bound to me by the friendship that grew up between us in those few days—however, he had the basis of an ideological background and a rather strong desire to be useful to me. It was by this means that he succeeded in overcoming his timidity.

As far as the rest goes, I had him perform in very small segments, one at a time, without even preparing them first. I would suggest the expressions while he acted. Inasmuch as we were shooting without sound, I could talk to an actor while he was performing. It was a little bit like a sculptor who makes a sculpture with little improvised blows of the chisel. While the actor was acting, I said to him “Look here”—and I told him each expression, one by one, and he followed them almost mechanically. I shot everything that way. He had the speech memorized more or less, and he began to say it. He had to—for example—take 10 steps forward, or move, or look at someone. I never told him beforehand, except in a very vague way, what it was all about, and gradually as he performed, I said, “now look at me . . . now look down there with an angry expression . . . now your expression softens . . . look toward me and soften your expression slowly, very slowly. Now look at me!” And so while the camera rolled, I told him these things. I prepared the action beforehand, in a very vague way, so that he would know more or less what he was supposed to do and where he was supposed to go. Whatever the nuances, the little movements, I suggested to him one by one. Prior to the shot, I gave him general movements and told him more or less what he was supposed to do. Then I explained these things more precisely while we shot. Once in a while I would surprise him—I would say to him, “Now look at me with a sweet expression on your face.” And while he did this I would say suddenly, “Now get angry!” And he obeyed me.

Didn’t this request make him attempt to imitate the way an actor he had seen got angry?

No. Actors would be tempted to do this, but one who is not an actor—for example, those whom I chose—would never do this. It’s not possible, because they have never confronted themselves with the technical problems of an actor—that is, he doesn’t have a technical idea of “anger,” he has a natural and genuine idea of anger.

I’ve done this rather often in other films. For example, I would have the person say a line that was not what it was supposed to be in the text. If he was supposed to say “I hate you,” I would have him say “Good Morning,” and then when I dubbed I would put in “I hate you.” Normally, I should have said to him, “All right now, say ‘I hate you’ as if you were saying ‘good morning.’” But this is pretty complicated reasoning for a person who is not an actor. So I simply tell him to say “Good morning,” and then in the dubbing I put in his mouth “I hate you.”

For dubbing, do you use non-actors or professionals?

I do both. That is, I take non-actors who generally reveal themselves to be splendid dubbers. For Christ, I was obliged to use a professional actor, so it depends on the circumstances. More than anything else, I try to balance everything out between the professional and non-professional performances. For instance, the boy in Mamma Roma did his own dubbing. But Franco Citti could not do his own dubbing, for even though he was bravissimo his voice was rather unpleasant. So I had him dub another character.

If you don’t give the non-actor much explanation of character, do you at least tell him the story?

Yes, I do, in two words. Just out of curiosity. But I never go into a serious discussion with him. If he has any doubts . . . if he says to me “what do I have to do here,” I try to explain to him. But always point by point, particular by particular, never the whole thing.

Do you add expressive gestures, which are not normally a part of the non-actor’s personal comportment?

No, I never have him do gestures that are not his. I always let him use the gestures that are natural to him. I tell him what he has to do—for example, slap someone or pick up a glass—but I let him do this with the gestures that are natural to him. I never intervene regarding his gestures.

If I want to underline some act, I do so with my own means, with technical means—with the camera, with the shot, with editing. I don’t have him emphasize it. Actually, I am very careful not to indicate to him the “intention,” because these “intentions” are the phony part of the actor.

Do you trick at all, in order to produce emotional responses?

Up to now it has never happened. If it were necessary, I’d do it. It’s never happened to me because my actors do not have petit-bourgeois inhibitions. They don’t care. They do what I tell them, generously. Franco Citti, Ettore Garofolo, the protagonist of La Ricotta, and my Christ as well—they gave of themselves completely, blindly. They don’t have that conventionality or false modesty of hypocrites, so I’ve never had to do this. However, if I had to trick, I’d do it.

Do you see a way of directing the bourgeois-class person who is a non-actor?

I was faced with this problem filming The Gospel. Whereas in my other films my characters were all “of the people,” for The Gospel I had some characters who were not. The Apostles, for example, belonged to the ruling classes of their time, and so obeying my usual rule of analogy, I was obliged to take members of the present-day ruling class. Because the Apostles were people who were definitely out of the ordinary, I chose intellectuals—from the bourgeoisie, yes—but intellectuals.

Although these non-actors as Apostles were intellectuals, the fact that they had to play intellectuals removed, no instinctively but consciously, the inhibition of which you spoke. However, in the case of one’s having to use bourgeois actors who are not intellectuals, I think that you can get what you want from them, too. All you have to do is love them.

How did you work with the intellectuals to rid them of their inhibitions?

The process was identical with that for the lower-class performers. With the former naturally, I used a language that was on a more elevated level. But my methods were the same.

Do you feel the need of knowing your people a long time before shooting, to make friends with them, to learn their natural gestures in order to use them later?

I had known Franco Citti for years, because he was the brother of a friend. I knew his character more or less. On the other hand, Ettore Garofolo of Mamma Roma—I saw him once in a bar where he was working as a waiter. I wrote my whole script around him without speaking to him further. Because I preferred not to know him. I took him and began to shoot after having seen him for just that one minute. I don’t like to make an organized and calculated effort to know someone. If you can intuit a person, you know him already.

Generally I have very precisely in mind what I’m going to do. Because I’ve written the script myself, I’ve already organized the scene in a given way. I see the scene not only as a director but also with the different eyes of the scriptwriter. In addition, I choose the settings. I go to these places and make an adjustment of what I’ve written in my script to fit the place where we are going to shoot. And so when I go to shoot, I more or less know already how the scene is going to go.

I did this for every film except The Gospel. With The Gospel, the thing was so delicate that it would have been easy to fall into the ridiculous and the banal and the typical costume film genre. The dangers were so many that it wasn’t possible to foresee them all. And it being so difficult, we had to shoot three or four times more material than necessary. In effect, most of the scenes I created in the cutting room. I shot the whole Gospel with two cameras. I shot every scene from two or three angles, amassing three or four times more material than necessary. It was as if I had done a documentary on the life of Christ. By chance. With the moviola, I constructed the scene.

Did you seek a particular style in the framing, and was this possible with two cameras going?

Yes, I always have a rather clear idea of the shot I want, a kind of shot that is almost natural to me. But with The Gospel I wanted to break away from this technique because of a very complicated problem. In two words it’s this: I had a very precise style or technique with which I had experimented in Accattone, in Mamma Roma and in the preceding films, a style which is, as I said before, fundamentally religious and epic by its very nature. And so I thought that my style—possessing naturally these qualities of sacredness and epicness—would go well with The Gospel also. But in practice, that was not the case. Because in The Gospel this sacredness and epic quality became a prison, false and insincere, and so I had to reconstruct my whole technique and forget everything I knew, everything that I had learned with Accattone and Mamma Roma, and begin from the beginning. I relied on chance, on confusion, and so forth.

All this was due to the fact that I am not a believer. In Accattone, I myself could tell a story in the first-person because I was the author and I believed in that story, but I could not tell the story of Christ—making him the son of God—with myself as the author of this story, because I’m not a believer. So I didn’t work as an author. And so this forced me to tell the story of Christ indirectly, as seen through the eyes of one who does believe. And as always when one tells something indirectly, the style changes. While the style of a story told directly has certain characteristics, the style of a story told indirectly has other characteristics. That is, if in literature I am describing Rome in my own words, I describe it in one style. But if I describe Rome—using the words of some Roman character—the result is a completely different style because of the dialect, the popular language, and so forth. The style of my preceding films was a simple style—almost straightforward, almost hieratic—while the style of The Gospel is chaotic, complex, disordered. Despite this difference in style, I shot all my films in little pieces all the same. Except the frame, the point of view, the movements of the extras were changed.

I have read that you have said that you have trouble with actors. Why is that?

I wouldn’t like people to take this too literally, not in a dogmatic way. In La Ricotta I used Orson Welles and I got along beautifully with him. In the film I’m making now I’m going to use Totò, a popular Italian comic, and I’m sure everything will work out fine. When I say I don’t work well with actors I’m uttering a relative truth—I want to be sure that this is clear. My difficulty lies in the fact that I’m not a professional director, and so I haven’t learned the cinematographic techniques. And that which I have learned least of all is what they call the “technique of the actor.” I don’t know what kind of language to use to express myself to the actor. And in this sense, I’m not capable of working with actors.

After your directing experiences with Anna Magnani in Mamma Roma and Orson Welles in La Ricotta, what have you learned about using professional actors as distinct from non-actors?

The principal difference is that the actor has an art of his own. He has his own way of expressing himself, his own technique which seeks to add itself to mine—and I cannot succeed in amalgamating the two. Being an author, I could not conceive of writing a book together with someone else, and so the presence of an actor is like the presence of another author in the film.

With Welles, how did you get a result you felt was fruitful?

For two reasons—first of all in La Ricotta Welles did not play another character. He played himself. What he really did was a caricature of himself. And also because Welles, in addition to being an actor, is also an intellectual—so in reality, I used him as an intellectual director rather than as an actor. Because he’s an extremely intelligent man, he understood right away and there was no problem. He brought it off well.. It was a very brief and simple part, with no great complications. I told him my intention and I let him do as he pleased. He understood what I wanted immediately and did it in a manner that was completely satisfying to me.

With Magnani, it was much more difficult. Because she is an actress in the true sense of the word. She has a whole baggage of technical and expressive notions into which I was unable to enter, because it was the first time I had any kind of contact with an actor. At present, I’ve had a little bit of experience and at least can face the problem—but at that time, I couldn’t even face it.

Now that you have experience, have you thought how you may overcome this acting “baggage” of the professional performer? You said you are using Totò in your next film—have you reflected upon your way of directing him?

Yes, I think the way to get around this problem is to use the fact that they are actors. Just as with a non-actor I use a whole series of things unexpected and unforeseen—leaving them to their own vital confusion (for example, when I tell them to say “Good morning” instead of “I hate you”), leaving them to the ambiguousness of their being—so I must use the actor specifically for his actor’s baggage. If I try to use an actor as if he were not an actor, I would be wrong. Because in the cinema—at least in my cinema—the truth always comes out sooner or later. On the other hand, if I use an actor knowing that he is an actor, and therefore using him for that which he is and not for that which he is not, I hope to succeed. Naturally, the character whom he interprets must be adapted to this idea.

It just happens that the characters in my new film are all ambiguous characters who have something real, human, profound about them, and at the same time something invented, absurd, clownish and fable-like. The double nature of the actor, Totò-man and Totò-Clown, this double nature can be used by me for my character. In Totò himself this double nature—man and clown, or man and actor—functions because it corresponds to the double nature of the character in the film.

Do you plan to explain to Totò this double nature you’ve outlined?

Yes, of course. As soon as I met him I explained that I needed a character just like himself. I needed a Neapolitan. Someone profoundly human, who as at the same time this art that is clownish and abstract. Yes, I told him right away.

Are you not afraid that now that he knows, Totò will try to play both the clown and the human being?

No, I told him to make him feel freer. Because I saw that he would worry about it. It’s the first time that he has worked on a film that has this kind of ideological content. Of course, he has made several good films, but they were always on an artistic level, without political commitment. So probably he was a little worried. In order to leave him completely free, I told him—so that he could go on doing what he had always done, so he won’t have to do anything different.

Do you rehearse a lot or do you shoot immediately?

I never rehearse. I shoot right away.

Does this impose simple camera work?

My camera movements are very simple. For The Gospel, I used camera movements that were a little more complicated, but I never use a dolly, for example. I’ve always shot in pieces. Shot by shot,. A few pans and very simple tracking shots but nothing more.

What are your observations about the aesthetic and technical characteristics of film as you have gained experience?

My lack of professional experience has not encouraged me to invent. Rather it has urged me to “re-invent.” For instance, I never studied at the Centro Sperimentale or any other school, and so when the time came for me to shoot a panoramic shot, for me it was like the first time in the history of cinema that a panorama was shot. And so I re-invented the panoramic.

Only a person with a great deal of professional experience is capable of inventing technically. As far as technical inventions go, I have never made any. I may have invented a given style—in fact, my films are recognizable for a particular style—but style does not always imply technical inventions. Godard is full of technical inventions. In Alphaville there are four or five things that are completely invented—for example those shots printed in negative. Certain technical rule-breakings of Godard are the result of a pains-taking personal study.

As for me, I never dared to try experiments of this kind, because I have no technical background. And so my first step was to simplify the technique. This is contradictory, because as a writer I tend to be extremely complicated—that is, my written page is technically very complex. While I was writing Una Vila Violente— technically very complex—I was shooting Accattone, which was technically very simple. This is the principal limitation of my cinematic career, because I believe that an author must have complete knowledge of all his technical instruments. A partial knowledge is a limitation. Therefore, at this particular moment, I believe that the first period of my cinematic work is about to close. And the second period is about to start, in which I will be a professional director also as far as technique in concerned.

But what have you discovered about film in an aesthetic sense?

Well, to tell the truth, the only thing I discovered is the pleasure of discovery.

You’re talking like Godard now.

I answered like Godard because the question is impossible to answer. Look, if I believed in a teleology of the cinema, in a teleology of development, if I believed in an end-goal of development, in progress as improvement . . . but I don’t believe in a “bettering,” an improvement. I think that one grows, but one does not improve. “Improving” seems to me an hypocritical alibi. Now, believing in the pure growth of each one of us, I see the development of my style as a continuous modification about which I can say nothing.

How do you conceive the structure of your films, what makes them move from one end to another?

It’s too demanding a question. For the moment it’s impossible to answer. But I would like for you to read in Cahiers an article I wrote. This question implies not only an examination of my films and my conscience, it brings up the question of my Marxism and my whole cultural struggle during the Fifties. The question is too vast. It’s impossible.

But let me say this now in a very schematic fashion. At this point, the cinema is dividing itself into really two large trunks, and these two different types of films correspond to what we already have in literature: that is, one type on a high level and another type on a low level. While cinema production until now has given us films of both a high and low level, the distribution apparatus has been the same for both. But now the organization or structure of the cinema industry is starting to differentiate . . . the cinema d’essai is becoming more important and will soon represent a channel for distribution through which certain films will be distributed, whereas the remainder of the distribution will take place normally. This will bring about the birth of two completely different cinemas. The high level of cinema—that is, the cinema d’essai—will cater to a selected public and will have its own history. And the other level will have its own story.

In this important change, the selection of non-actors will be one of the most important structural aspects. Probably the structure of this high level cinema will be modified by the fact that no longer will there be an industrial organization hanging over it. And so all kinds of experiments will be possible, including that of using non-actors, and this will transform the cinema even stylistically.

In Cahiers, do you speak of aesthetic structure?

The structure of cinema has a special unity. If the structuralist critic were to describe the structural characteristics of the cinema, he would not distinguish a story cinema from a non-story cinema. I don’t believe that this story distinction affects the structure of cinema; rather it affects the superstructure—I mean the style. The lack or the presence of a story is not a structural factor. I know that some of the French structuralists have attempted to analyze the cinema, but I don’t believe that they have succeeded in making these distinctions.

Literature is unique, it has unity. Literary structures are unique and include both prose and poetry. Nevertheless, there is a language of prose and a language of poetry, although the literary structure is one. In the same way, the cinema will have these distinctions. Obviously, the structure of cinema is one. The structural laws regarding any film are more or less the same. A banal western or a film by Godard have structures that are fundamentally the same. A certain rapport with the spectator, a certain way of photographing and framing are the identical elements of all films.

The difference is this: the film of Godard is written according to the typical characteristics of poetic language; whereas the common cinema is written according to the typical characteristics of prose language. For example, the lack of story is simply the prevalence of poetic language over prose language. It isn’t true that there isn’t a story; there is a story, but instead of being narrated in its integrality, it is narrated elliptically, with spurts of imagination, fantasy, allusion. It is narrated in a distorted way—however, there is a story.

Fundamentally, the distinction to be made is between a cinema of prose and a cinema of poetry. However, the cinema of poetry is not necessarily poetic. Often one may adopt the tenets and canons of the cinema of poetry and yet make a bad and pretentious film. Another director may adopt the tenets and canons of the prose film—that is, he could narrate a story—and yet he creates poetry.