Interview: Paul Mazursky

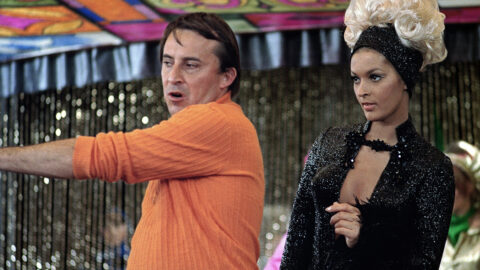

This interview took place June 1977 in a coffee shop around the corner from Mazursky’s Greenwich Village apartment. He had just completed shooting An Unmarried Woman.

One of the things I noticed on your set is how many times you go on a first take.

Paul Mazursky: I may print the first take a lot, but I almost always do more than one take. Very often the first take has some kind of first-time thing that in a movie, for the strangest reasons, is different from all the other takes. Even though there’s a craft—and even though trained actors like Alan Bates and Jill Clayburgh and Michael Murphy can repeat what they’ve done, and I would say at least half of the time repeat it better—some of the time, part of the time, something instinctive takes over. You don’t know it is the thing until you see the dailies. You see that clearly was better than all the later takes. Especially in a master shot. I like masters. Also, you have to remember that a lot of what you saw had been rehearsed, or discussed, or prepared extensively. And then at the moment of the first take, I remind them, privately, a little bit here and there. Sometimes I don’t even do that.

How much preplanning of angles do you do?

A lot. But I change a lot. I plan it a lot and I change it a lot. This movie I prepared longer than any other movie I’ve ever done. And it was not the hardest movie to do technically. Alex in Wonderland was much more difficult; even Blume in Love, where I was shooting in the piazza in Venice with a thousand people. But I wanted to get into SoHo life, and I wanted to be around a lot of women. I actually wrote the script in May and June of 1976, made a deal, and came to New York in mid-September. Then I spent six months, a long time, preparing: looking for locations. And in my case that means really looking.

How much of this picture has to do with the move you made from L.A. to New York?

It’s clearly a New York picture, and none of it has to do with my moving here. I could have written it in California. I wanted to work in New York again, I wanted to be in New York again. I like the idea. I enjoy the vitality of New York and the energy and the street life. I enjoy jogging in the park and accidentally bumping into Tom O’Horgan on the way back and sitting and talking for 15 minutes about Caligula, In L.A. you could jog for 25 years…

The reason I ask is that your movies almost always have very specific social situations. Both the subsociety and the larger society are almost always immediately recognizable. That may have something to do with your choice of subjects from the middle class, which is not all that usual in American film.

It’s unusual, and it’s dangerous at the box office in a strange way. It’s the strangest thing I’ve ever seen. I guess people at this point in time would prefer to see alienated outsiders who are certainly not middle-class people. Science fiction is now coming in, and that’s nor about any class, really. And the big chase, horror things are beyond class: they’re really genre. But what I’m doing was really very normal in the Thirties and Forties. I’m not saying I would have been one of a hundred guys, but there were certainly people doing it then.

I suppose that’s why you’re often compared to Preston Sturges and Frank Capra.

Yes, Sturges, Capra, but I consider myself…well, I don’t say I was influenced by them directly, but even people tike Lubitsch and George Cukor. I don’t consider myself like them. But there were so many of them who made movies about people whom one understood to be not so different from oneself. The appealing thing about Annie Hall, for a lot of people, is that you’re seeing a film that doesn’t offend your intelligence: we talk that way, we know about that. We stand and listen to pretentious people on the movie line. There are a lot of bright people around. Very few movies are made thinking of the audience as that fairly intelligent middle class.

But Allen’s persona is still an outsider’s persona, while your people are generally integrated into the society in which they’re living. They’re not uncomfortable.

Well, Woody’s character himself is uncomfortable with women. You never really knew that much about his relationship with society. My people—at least you become aware of the fact that they’re part of the society. In most films that I see you aren’t even aware that there is a society. There’s just a bank to be robbed.

Let me put it another way. In your films, the characters always have jobs. You don’t wonder what Erica is going to do to make a living when she splits because you know where she works. And even when you’re dealing with artists, you see it as work.

They have reality, some kind of reality. You know, American film has never dealt with the artist with any real honesty. I don’t want to advertise this picture too much as being about artists, but I think you will see in this picture an artist at work. Because they’re flesh-and-blood people, real people, who have egos, who talk about money, who think about sex, who eat, who do the tangible things most of the people I know do. We all have certain things in common.

The thing we don’t all have in common is we have different anxieties. Some people are not the least bit uptight about certain things and others are. I used a West Coast phrase: uptight. I mean, care about, are passionate about. It’s one of the great differences about New York: you don’t find that intense passion about how much a movie made. You find a lot more passion about other things. That’s what stimulated me, things as far apart as: Are they going to put up this highway on the West Side? Is Tom Seaver going to be traded? Is there going to be a street fair? Is it going to rain? The curious thing is that some of my California friends who have come here have literally been frightened. I’m shocked. Europeans come here and “It’s like Paris, but…” or “It’s like London, but…”

How much is this picture a companion piece to Blume?

It’s no more a companion piece to Blume than Blume is a companion piece to Bob & Carol. An Unmarried Woman is about the subtle place a lot of women find themselves in. Women who are not with two strikes against them from the start: being very poor, being ugly, being very neurotic, having a terrible life. This movie is not about those women. I wanted to do a movie about the middle-class women who have very happy lives, a lot of opportunity, for whom things are good—but who, in essence, are psychological slaves. They really live through their husbands, through the man. Even the ones who appear not to be. That’s all the movie’s about.

In a strange way, it’s even a companion piece to Alex in Wonderland. Alex is married and has two children; a lot of Alex has to do with this conflict between his work and his family, which is my favorite subject. I just started to read Gail Sheehy’s book Passages—I’m glad I read it after I finished shooting the movie—and I realized the Michael Murphy character is going through male menopause.

Let’s put it this way. In Blume in Love I wanted to deal with the middle class romantically. The middle class, I feel, is a class which is never dealt with romantically, although the passion which is felt there is as grand a passion as in the movies we used to see with Grace Kelly. In Blume in Love a woman finds her husband cheating and kicks him out. But the first and foremost thing in her mind was having a baby. So she takes him back. An Unmarried Woman is substantially different; it’s about accepting being on your own. It doesn’t mean being lonely, or being alone forever. It’s accepting that it’s okay in this society to be on your own. And that’s it.

Even so, there’s a real sense of family in the script. The relationship between Erica and her daughter seems essential to the film.

More so even than in the script. The girl [played by Lisa Lucas] will emerge as a major character in the movie. For me, the central things in my life have been my family and my work. I have two children and I’ve been married 24 years. The warmth and closeness obviously means something to me. I don’t have an explanation, that’s the way it is. The central things in some people’s lives are their work and their yacht. I’m not making a comment that that’s any worse than the family, it’s just that’s my preoccupation.

There’s a line in the movie when Erica talks about the meetings her club has. She says they’re a cross between Mary Hartman and Ingmar Bergman. I think that’s kind of where middle-class life has gotten. It’s on the edge of soap opera and the edge of real; it’s alienated and confused, almost tragic. It’s become popularized in one way or another, but I haven’t seen it dealt with much in American cinema on a level which communicates real feeling. I’ve seen it dealt with through humor, a bit. But not with real feeling.

Was it difficult to make a woman’s picture at this point?

I don’t know if this is a woman’s movie or not. I don’t know what that means anymore. As opposed to Black Sunday it’s a woman’s movie. But a lot of guys are going to want to see this picture. A lot. Everyone whom I meet who asks what this film is about says, “Oh, you mean my friend Marion.” They’re all right in there with someone who they see in that spot.

I wanted to get inside a woman’s head. I’ve felt that all the pictures I’ve done, I’ve done with men. I put myself inside a man’s head, using myself a lot. I wanted this time to think like a woman. That’s one of the reasons there was so much rewriting. I changed a lot of things based on experiences I had. There were also many things the women I cast in the film—Jill Clayburgh, Lisa Lucas—wouldn’t say. They’d tell me why, and I’d say, “Well, what would you say?” and I’d let them say that. I used a real therapist; I wanted a woman, and I had to change what she said based on what she is. In other words, the only thing I could have done was get a woman to help me write it. I thought about that for a while, but in the end I think it worked out.

Was it a difficult film to finance?

The attitude at the studios now is to prefer to do pictures that cost more money. If I had gone to them and said this is a picture which will cost $5 million, we’ll go for Faye Dunaway, I think it would have been a one-second sale. But I have a peculiar situation. I’m given complete and total freedom by major Hollywood studios, which have given me essentially $2 million. I’ve done this now six times. No one has bothered me. They’ve left me alone every single time. I’ve cast whom I want. They would prefer that I do one for $6 million rather than $2 million and shore it up with a couple of names. It’s easier to sell. And I would have done it with a big star if I thought there was one who was perfect for the part. Generally speaking, to get a woman’s film financed, I would say it’s much more difficult. Barbra Streisand is the main financeable female star. Past Barbra, I don’t think there’s anybody. A Star Is Born was slaughtered by the critics but did not slow up for those it served.

Why did you choose to act in A Star Is Born?

Frank Pierson is a friend of mine, and he told me about the script. I was finishing up the first draft of Unmarried Woman and I thought it would be fun to act. I’d love to act again in somebody’s picture.

Does having been an actor help you direct?

It helps a lot. I mean, I really know the pain of waiting all day to do my shit, or the pain of pretending you know what you’re doing when you’re not really sure, or the pain of not having enough rehearsal. But forgetting all of that, it’s fun.

Do you think your movement from actor to writer to director has anything to do with your habit of casting against type?

Possibly. I just love the idea of going against the obvious. It’s risky, sometimes. For example Ginger, the hitchhiker in Harry and Tonto: it’s just so obviously righter to make a choice like Melanie Mayron than go with a California cutie-pie with long blond hair. There’s nothing to think about. But you don’t know that until she walks into the room and reads for you. When you meet her, she opens her mouth and you say, “That’s it.” I didn’t know that when I was writing it.

Your casting is unusual. Alan Bates is surprising.

Tell me why?

A British Jew is a surprising thing to see.

I think this film is the least Jewish film I’ve ever made, but it’s still got Jewish in it. I’m Jewish, I was brought up in a very Jewish neighborhood, but the Jewish thing in America has changed; I think the Jewish alienated schlemiel hero is a thing of the past. As for Alan’s being Jewish, it wouldn’t’ve been surprising in the Forties when Ronald Colman, Stewart Granger, David Niven were all around. We didn’t care if they were British. And it wouldn’t’ve been surprising if I’d said, “Should I use one of the five great actors in the English-speaking world or should I go for an American?”

I try to cast who I think is perfect for the part. I don’t try to cast a star first. And if you try to cast who you think is perfect for the part, you very often eliminate most of the stars. It’s a very tricky game. You’re casting a 22-year-old Jewish boy—I would have cast Bob De Niro had he been available. He was not available. I never had a discussion with him. But I think he’s so extraordinary. I think he could have made the age. I don’t think Dustin could have made the age. Physically. I don’t think Pacino could have made the age physically. The only other person I talked to was Richard Dreyfuss, who wasn’t really a star then, and our negotiations didn’t work out. So I was obviously confronted with finding an unknown. After looking at a hundred young men between the ages of 18 and 38—a lot of them lied—I found Lenny Baker, this extraordinary, strange, off-centered, gangly young man, 30 years old. I’d never seen him work. I didn’t test him. I just read with him and spent about five sessions over a year or two. And that was it. I felt he was the closest thing to the part.

In the case of Art Carney, it was the same kind of story. Nobody wanted to make the movie. They were willing to make it if I used a very famous actor in his fifties who was completely wrong for the part, so I wouldn’t do it. And the only actors I was really interested in were people like Melvyn Douglas, who was no longer physically able to do it. I had talked about Olivier for a brief while, but Olivier felt he was not right for the part. He felt I should use an American. The studios I talked to about Olivier didn’t want to go with him. That’s the truth. Then the idea of Art Carney came up. He read it, and he was filled with doubt. He was 56 or 57 years old. “I can’t play an old man,” he said. I could tell from sitting and talking with him that he was Harry. That was it.

Every now and then I’ve probably made a mistake, but I don’t think I’ve ever made a major mistake. Not from my point of view. There are people who felt that Susan Anspach was a mistake, that I should have used an extraordinarily beautiful woman. They wanted Candy Bergen. I deliberately wanted to use someone who was attractive, who tried to make her ordinariness extraordinary. The way middle-class people do.

I thought Blume would be a hit. The early reaction was extraordinary. But it was badly distributed: they released it two weeks after A Touch of Class, another George Segal film.

On the other hand, it’s having its life.

Oh, they all have their life. Next Stop, Greenwich Village is a smash hit in Scandinavia. It broke all records in Finland—who knows why? It played six months in one theater in Paris. Made a lot of money in France and Belgium. Who knows how to answer that? Why should a picture called Next Stop, Greenwich Village be more successful in Paris than in New York?

Do you adjust to the actors after you cast?

Absolutely. I totally adjust to the actor. Always. For example: I needed two things from the man who played the Saul Kaplan role. One, I needed a really good actor; nothing less would serve in a role which appears on page eighty. Two, he had to have a genuine, immediate presence, one that doesn’t take a long time to be felt.

The original role was not written as British. The original rule was just written as a guy. But when I cast Alan Bates he said, “I’m not American. How can I play it?” I said, “Don’t worry. Play him like one of a hundred thousand people living in New York right now who are English, but who have been living in New York for about 10 years. I know five of them; I’m sure there are another 99,000 somewhere.”

You mentioned the psychiatrist. It strikes me that very often there are guru figures—the acting teacher in Next Stop, Chief Dan George in Harry and Tonto—who exist for a pivotal moment and then disappear.

I’ve never thought of it in that way, although what you say sounds okay. She’s an interesting figure; she represents more than a psychiatrist. She represents the options available to women. She is unique. And for the role I deliberately chose a unique woman, Penelope Russianoff. She’s six foot two inches rail; she’s 58 years old; she’s extremely witty; she’s extremely brave. She functions in a way that’s a little different than the average one would expect of a psychiatrist; it’ll throw people off momentarily. She has compassion, she has loyalty. I think it’s very important for Erica to encounter a woman like that, rather than a conventional psychiatrist. Secondly, not only have I done a lot of psychiatric stuff in movies, but I’ve seen a lot; it had to be awfully good for me to get away with it again.

One of the things about the structure of your films—it’s most obvious in Harry and Tonto—is that they’re very picaresque. They’re almost illustrative. When the psychiatrist shows up at the party with a woman: there’s an option. When Erica goes on her “date”: there’s an option.

The other way is so boring. One is influenced by Italian neo-realism or something. The crisis may be greater but there isn’t much plot; it’s just incidents. I don’t know anymore. I think of my films as very American. I think I fooled around with wanting to be European in Alex. Now, they are what they are. As far as plot construction: I don’t want to compare myself to Woody Allen, somebody I like, but there’s no plot in Annie Hall. There’s no crisis really.

The crisis seems to come at the end of your films; they almost always end at the beginning. It’s almost a process of regeneration.

I always try for it. It’s definitely a mark in my films. I try for it, I want it. I believe in it, and I don’t give a shit what anybody says, critically or otherwise. I believe in the affirmation of life. If we lose that hope, if we lose the possibility of it, we’ve lost an awful lot. I believe that buried deep in the heart of a lot of cynics is that affirmation.

At the same time, they’re tentative beginnings. You don’t know what’s going to happen to Lenny Baker in Hollywood, you don’t know what’s going to happen to Blume or to Erica…

No question about it. I feel that way, personally. I always feel that way when a film is over. I don’t know what’s going to happen next.

Perhaps as a result, your movies become about possibilities.

Which is, I think, a very contemporary, existential fact, to use a lot of long words. In the past, the possibility of change wasn’t psychologically really a fact. One tended to accept one’s fate, whether it was the bottom, the middle, or the top, as being the state one was going to be in forever. That took away a certain amount of dread and anxiety, and fear and trembling, because one’s dread and anxiety and fear and trembling was just about dying, not so much about “Can I change my psyche?” Pre-Freud. But once that revolution took place, the possibility of change became a constant double-edged sword.

Martin, Erica’s husband, has a line: when Erica says, “You’re a strong man,” he says, “I don’t feel strong. I think I’ll give up my job and become a disk jockey.” Well, he’s fantasizing, but he means it. He means it, the poor sucker. He doesn’t know what to do next. He’s made money, he’s earned respectability, whatever that is. He’s got a beautiful wife, a nice child, he’s doing well, he lives okay, he fucked up. And he doesn’t know what it is. The possibility of change exists all around him. He’s been fed it. A very common condition, certainly for the middle class, and I think now it’s leaked down to the lower middle very nicely.

In a sense, that’s the major theme that runs through your movies.

I’m not going to say that. If you want to say that, you can say that. I don’t think about it. But a lot of people might think Harry and Tonto is about the fact that one should accept death. The end of the film tells you what it’s all about. The last image is a child building a sand castle and the old man elects to help her build it. And what does she do? Does she say thank you? Does she cry? No, she sticks her tongue out at him. Now, you can interpret that a lot of ways. It’s loaded with symbols: the sun is going down. Well, I didn’t know the day I shot it quite why or how I was doing. I just knew what I wanted to do, and I got my own kid out there, and I told my kid, do whatever you want to do. I don’t care what you do, just stay around the sand castle, because I have to shoot it. So Art started singing to her—you can’t really see it—and he said something to her, and she stuck her tongue out at him, and he started to laugh. For me, the whole movie is about that. But I certainly can’t analyze it.

In Harry and Tonto, in An Unmarried Woman, you’re doing something very dangerous, which is dramatizing an internal state.

Very, very dangerous. Dangerous commercially.

I actually meant it’s difficult to do. It could easily fall off into something overly explicit.

Between Mary Hartman and Ingmar Bergman. It hovers. But what I’ve seen works, I must say. I feel very good about it. You never know what’s going to happen. To me that’s much more exciting. Maybe one day I’ll make a big adventure movie—the helicopters, the special effects, the 15 million bucks—it could be an interesting commercial vehicle. But whether that’s an exciting journey to be on—that’s a personal choice. To me, inner journeys are much more exciting.