Fit to Print

Literal-minded viewers will be pleased to know that Page One: Inside The New York Times occasionally shows what the title seems to promise: the process of deciding which stories get to live on the most valuable piece of real estate in the newspaper business. These scenes, however, are few and brief. For most of its 88 minutes, this documentary by writer-director-cinematographer Andrew Rossi and his co-writer, Kate Novack, is preoccupied not with the world of events you might read on page one, but with the question of whether newspapers can afford to keep printing anything there at all.

The witnesses followed throughout the film do not represent the full spectrum of the Times newsroom but are primarily a tight group of staffers for the business section, all of whom are assigned to report on the media (which includes the Times and its competitors, near and distant). As for the movie’s time frame, Page One shows you the ups and downs of print journalism roughly from October 2009 through October 2010—though exactly where you are in the timeline at any given moment is open to some question.

Page One incorporates 10 major stories from the period, selecting them to illustrate the forces that now affect even the magisterial Times. Here are those stories arranged in a straight line: the Times announces it will cut 100 employees from its newsroom (October 2009); Comcast buys a majority share in NBC (December 2009); the Times announces it will start charging for access to its website (January 2010); Apple unveils the iPad (January 2010); CNN.com begins webcasting videos supplied by the self-consciously raffish Vice magazine (February 2010); ABC News announces extensive staff cuts (February 2010); WikiLeaks posts an online video showing a deadly attack in Baghdad by U.S. forces (April 2010); the Times publishes a redacted archive of documents from the Afghanistan war, supplied by WikiLeaks (July 2010); NBC News airs a live broadcast of U.S. troops leaving Iraq, with the claim that its report constituted an official announcement of the end of combat (August 2010); and ugly details about the bankrupt Tribune Company emerge in a lengthy exposé by media desk reporter David Carr (October 2010).

But in Page One, the dates of these events are elided, and the order of presentation is scrambled. Plot the 10 stories on graph paper according to the movie’s scheme, and you’ll get a zigzag that could land you in the cardiac care unit.

Why do I make a big deal of this skipping around? Two reasons. First, Page One shows the writers and editors at the Times working ceaselessly to get their facts straight, with the surprise star of the film, David Carr, appearing as the snarling mongrel guard dog of reportorial integrity. (“I’m not a journalist,” Vice magazine founder and roving correspondent Shane Smith explains to him early in the movie, eliciting a warning growl: “Obviously.”) If I didn’t acknowledge the temporal fogginess of Page One, I couldn’t walk the streets of Midtown without nervously searching every shadow for Carr. And that would be a superfluous anxiety—because (reason number two) the absence of any clear order of events is so prominent a feature of Page One that it almost amounts to a statement of artistic independence. This movie about a day-by-day enterprise dispenses completely with before-and-after.

Why do Rossi and Novack so strongly assert the filmmaker’s prerogative to re-order time, even at the risk of making the viewer feel unmoored? The justification, in part, lies in the way they present their themes. Page One front-loads its narrative with stories that are not about the newspaper business per se but about online media, cable television, and the decision by entertainment conglomerates to shrink their investments in broadcast reporting. Much is made of the ability of WikiLeaks to break a story on YouTube, without having to rely on any news organization; much is made of reporter Brian Stelter’s rise from being a self-employed blogger to having a coveted staff position on the Times. If the argument being developed isn’t completely determined by technology—Rossi and Novack are too sophisticated for that—Page One nevertheless gives you a strong impression of the old print world being overwhelmed by the new and the wired. The opening images of the Times printing plant—shots that are lovingly composed and richly colored, at once heroic and nostalgic in tenor—give way to the blur of online videos. Background information about the bankruptcy of newspapers around the country comes across not in headlines or talking-head testimony but through a montage of broadcast reports, evidently chosen with a preference for the shoddy-looking.

Only after giving you this protracted overview of the media landscape does Page One slot in the report of major staff cuts in the Times newsroom, and then the stories about how the Times is changing the way it does business: the decision to accept WikiLeaks as a source, the plan to establish an online paywall, the hope that the iPad might offer salvation.

In short, Rossi and Novack abandon a chronological structure for an expository one. But there’s a second structure built into the film as well—that of the old-style platoon movie.

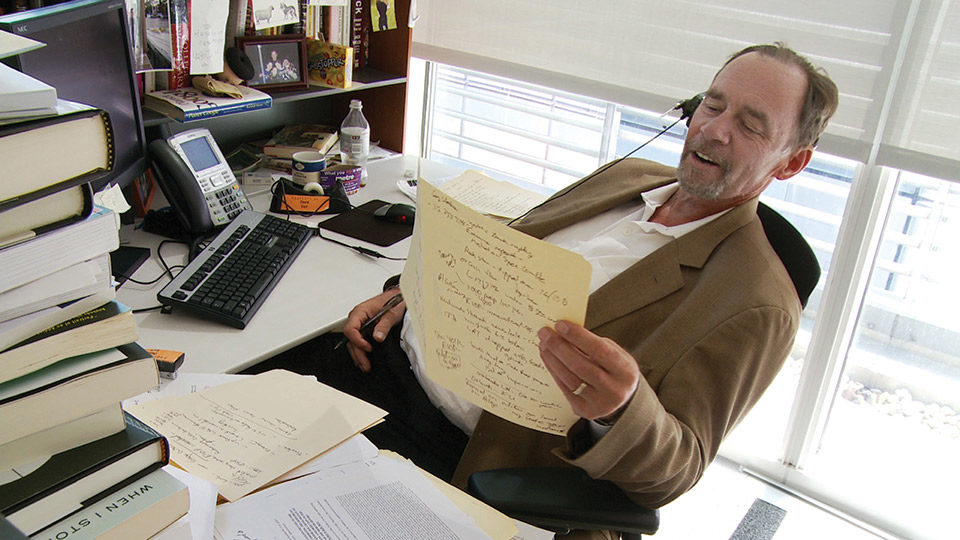

Above all, you have David Carr. To allow him to emerge as the film’s unexpected champion of old-style journalism, Rossi and Novack rearrange chronology to create an intermittent but ongoing narrative of his reportorial feats and public appearances. It’s an impeccable decision. Like a gaunt figure from the pre-gentrified Times Square, glowering and possibly dangerous, Carr shambles incongruously into the elegance of the new Times Center skyscraper, bringing a jolt of rude, messy life into Page One with his every appearance. He is the ghost of newspapers past, with printers’ ink somehow still running in his veins. He is the character actor who effortlessly steals Page One from its leading man, the Central Casting–handsome managing editor Bill Keller.

A man who has overcome drug abuse, imprisonment, and hand-to-mouth living, Carr carries himself like William Burroughs and speaks in the choked voice of Tom Waits, only an octave higher. He is the very image of the hipster who has lived hard—and the aura about him of the redeemed sinner lends both authority and fearlessness to his displays of moral rigor. He tongue-lashes anyone who ignorantly belittles the work of the Times, excoriates anyone stupid enough to think an aggregator’s website can substitute for consistent field reporting, and when laying bare the corporate culture of the Tribune Company, will not yield to either the distraction or the intimidation of lawyers. High principles combined with a liberating, foul-mouthed lack of all pretense: in Carr, Page One has its irresistible, truth-telling survivor.

Rossi and Novack clearly hope that’s what the Times itself can be—an institution that both survives and tells the truth—and so they shape Page One according to their desires. In the first half of the movie they call up the threats and challenges that face the paper (and also acknowledge some of the damage the Times has done to its own reputation, as with Judith Miller’s notorious yarns about weapons of mass destruction in Iraq). Then, in the second half, they build up the case for the ongoing value of the Times. Sometimes they do this by showing a behind-the-scenes editorial decision—as when Bruce Headlam and his writers wisely refuse to lend credence to NBC’s claim that combat has ended in Iraq—and sometimes by stepping up their deployment of Carr as the newspaper’s fiercest advocate.

So the platoon structure and the expository structure of Page One combine into a salvation narrative, for David Carr and for The New York Times. I make that statement with no mockery intended. Only uncommonly complacent people, of the sort that the Sulzbergers’ distant relatives used to call “all-rightniks,” fail to recognize the need for rescues; and only the fatuously judgmental, who have never struggled to get the facts straight on deadline, can think the world would be better if the Times were to disappear. The rest of us can enjoy and respect the recomposed reality of Page One. It’s an honestly hopeful film—even though it does take you out of time to put you inside the Times.

Stuart Klawans is the film critic for The Nation.