Out of the Past

Sing a song of sad young men.

Glasses full of rye.

All the news is bad again.

Kiss your dreams goodbye.”

—“The Ballad of the Sad Young Men”

Lyrics by Fran Landesman

Let’s go back in time. To a time when gays and lesbians were considered inferior forms of human. To a time when the idea of a bi- or fluid sexuality was roundly deemed a myth or, worse, an aberration. To a time when transgender people were considered social pariahs or perhaps attractions to be gawked at publicly. When same-sex couples had to fight to be treated as equals in the eyes of their government, neighbors, even families. To a time when politicians used them as fodder for their own gain, whether they approved or disapproved of them, or pretended to do either for the sake of their constituents. To a time when “coming out” meant possible social and familial rejection and an uprooting of one’s life, often at a fragile early age. To a time when gay people were stigmatized by their innate sexual needs. Let’s go back to a time when misconceptions about gays and lesbians abounded, when our domestic and sexual lives, our dreams and desires were considered strange or at least so outside the dominant culture that they were better left undiscussed. To a time when our visibility and media representation was minimal, if it existed at all.

You’ve probably caught my drift: time travel isn’t necessary for us to witness firsthand the struggles of gay, lesbian, bisexual, and transgender people. To different degrees, all the realities listed above are persistent, applying as much to today as to any period in the past century in the West. These pains only grow all the more acute from the enormous strides that have been made. Nevertheless, historians tend to divide gay history into discrete halves, with two easy signifiers to differentiate epochs: pre- and post-Stonewall. That is, before and after the events of June 28, 1969, when a fed-up and ever-growing band of patrons at Greenwich Village’s Stonewall Inn refused to go gently into the night while police conducted one of their frequent raids, leading to a riot. Such simplifications of history tend to devalue the efforts of those who came before and after—those who laid the groundwork for the struggle and those who kept it alive. Nevertheless, Stonewall lingers in the American consciousness, and it stands as the very unofficial, very diffuse beginning of the gay-rights movement. Because of this, there also persists an idea that there is such a thing as a fixed pre- or post-Stonewall identity or attitude: broadly, the closet was then, the world is now. That was Shame; this is Hope.

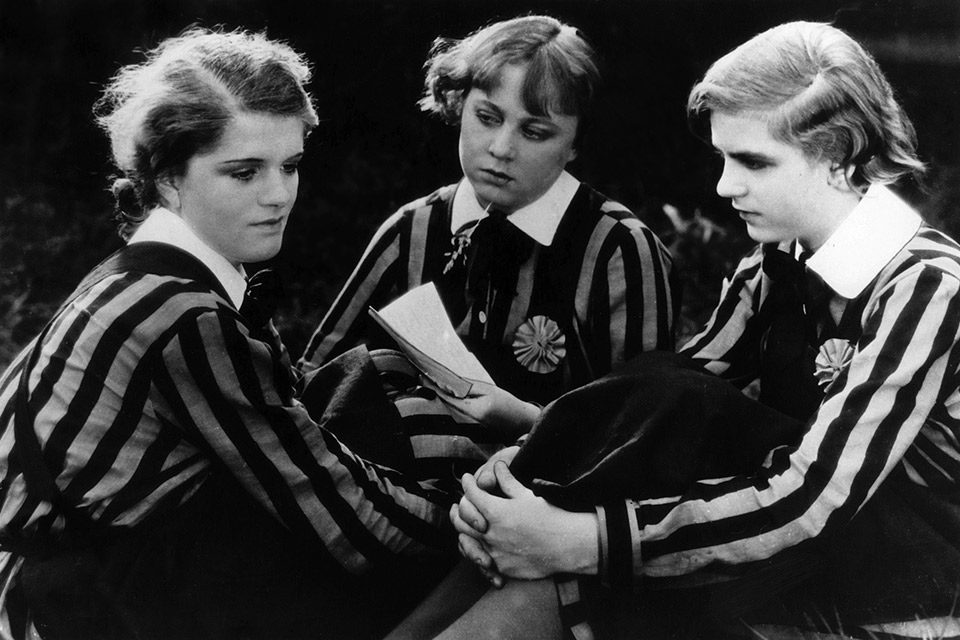

Madchen in Uniform

To try and chart the history created by this false binary in cinema is an entire other beast. When one considers films tagged as queer, one probably first thinks of provocations: perhaps the films of Rainer Werner Fassbinder in Germany in the 1970s; or the aesthetic austerity measures imposed by Derek Jarman in England throughout the 1970s and ’80s; or the quiet emergence of the New Queer Cinema movement in the U.S. in the ’80s and its explosive continuation into the ’90s, when filmmakers like Gregg Araki and Todd Haynes and Kimberly Peirce and Rose Troche were taking no prisoners. Yet to only focus on such confrontational, strikingly confident cinema blinds us to the history of queer films that we would now consider “pre-Stonewall”—films that dared to identify themselves as in some way homosexual but whose forthrightness was just as often tied up with ingrained, conflicted feelings of shame. There is no one way to describe the many disparate gay-themed or gay-informed films made over these earlier decades of the 20th century, but many of them are contradictions, finding repression in liberation, desire in loathing, bitterness in empathy, and they remain all the more fascinating for it. These are films that were, out of circumstance, caught up less in the political fight for freedom than in the electric impulses that careen through our brains. These are films that we now tacitly, implicitly refute, no matter their erstwhile radicalism. We tend to love classic movies, books, and songs—unless they seem hopelessly outmoded, the irredeemable products of an earlier era not yet caught up with our imagined progressive values (which is related to why people snicker when they go to old movies). As queer theorist Heather Love wrote, gay people have historically been branded as “nonmodern or as a drag on the progress of civilization.” If, as she continues, “texts or figures that refuse to be redeemed disrupt not only the progress narrative of queer history but also our sense of queer identity in the present,” then there would seem to be nothing more of a drag to the savvy contemporary moviegoer than politically démodé gay cinema.

Our implicit dismissal should make such films all the more crucial to consider. What may surprise viewers who watch the wide variety of selections in the Film Society of Lincoln Center’s series An Early Clue to the New Direction: Queer Cinema Before Stonewall, programmed by Thomas Beard, is the electrifying desire and sensuality coursing through them, which deepens and complicates their otherness. These titles offer such a diversity of tone, theme, genre, and format, and hail from so many different eras and countries, that one can’t help but realize that even the term “gay cinema” itself is irreducible. By and large, these aren’t films concerned with “visibility,” but with the importance of those invisible longings that make us human. Beard, who says he spent many years researching this series, came to “understand that the homoerotic imagination surfaced throughout cinema in manifold ways prior to gay liberation, and its presence wasn’t merely limited to coded glances and flashes of innuendo.”

Watching a lot of these films in quick succession can generate a Fantasia-like effect, as though they’re all on the same hallucinatory continuum. The radical promise of the early 20th century connects the gracious goofiness of French trailblazer Alice Guy-Blaché’s slapstick Western one-reeler Algie, the Miner (1912), in which an effete dandy prone to kissing men on the lips must prove his manhood for his future father-in-law; Sidney Drew’s slapstick A Florida Enchantment (1914), in which a magical seed turns a straight woman into a chic lesbian (alas, when an under-the-influence man cross-dresses, he is chased by an angry mob off a dock and drowns); and Carl Dreyer’s bisexual love triangle Michael (24), with Walter Slezak as the piercing-eyed object of master painter Benjamin Christensen’s affections (a film incidentally based on the same source novel as another offering in the series, Mauritz Stiller’s 1916 Vingarne—there was something in the air, indeed). Austro-Hungarian theater and film director Leontine Sagan’s adaptation of the play Mädchen in Uniform (1931), set at an all-girls boarding school, seems to coast on similar erotic fumes as George Cukor’s tonally opposite cross-dressing flop Sylvia Scarlett (35). The jolting empathy of Ed Wood’s sensationalistic yet ultra-personal cross-dressing saga Glen or Glenda (51), with its head-spinning mix of documentary-style direct address and surreal flourish (including, in case you didn’t know, a left-field lesbian bondage dream sequence), becomes inseparable from Pasolini’s Foucault-approved nonfiction experiment Love Meetings (64), in which the provocateur poet conducts man-on-the-street interviews with Italians of all shapes, sizes, and classes to gauge and challenge their tolerance levels for sexual “abnormality”—a true queer film avant la lettre.

Un chant d’amour

If any single title could stand in for the sublimated yet radical titillation of all pre-Stonewall gay cinema, it’s the 26-minute Un chant d’amour (50), the one and only feature made by Jean Genet, and a complete sensual experience: film as erogenous zone. Homoerotic desire boiled down to its essence—to its scent—it’s a jailhouse love song that wordlessly speaks for its otherwise unabashedly verbal author’s lifetime of desire and social stigma. Even if Genet’s film works best for committed admirers of the male armpit, it’s impossible for a viewer of any persuasion not to grasp the film’s irrepressible, undulating waves of longing. An impressionistic barrage of sexually frustrated prisoners grasping for each other and at themselves, their musculature bathed in chiaroscuro light as they lovingly move their hands down their bodies while they’re watched by drooling, baton-wielding guards, Un chant d’amour is an all-consuming work of art that aims to liberate the viewer through erotic fantasy. Banned for decades in Europe and the U.S. for its explicit—if elusive—imagery, Genet’s film is the roiling lava from which all gay cinematic desire springs.

Since such desires were—are—seen as aberrant by the dominant culture, they are necessarily the province of movies made outside of the industrial mainstream. In Un chant d’amour, as in Kenneth Anger’s eternally gutsy literal crotch-explosion Fireworks (49) and Gregory Markopoulos’s darkly meditative Twice a Man (63), gay male love crouches in crevices and shadows. Even when it’s frenetic and unabashed, as in James Sibley Watson and Melville Webber’s biblical free-for-all Lot in Sodom (33) or film cultist Jack Smith’s monumental Flaming Creatures (63), non-hetero extremity can only assert itself away from the prying eyes of the mainstream. The only features included in the lineup representing Hollywood’s approach—which isn’t “kid gloves” as much as wool mittens covered in saran wrap—are Hitchcock’s Leopold and Loeb riff Rope (48), the ultimate uncut come-on (appearing to be just one long, hard take); Vincente Minnelli’s Tea and Sympathy (56), a gorgeously humane yet severely altered Technicolor film of Robert Anderson’s stage play, featuring a studio-imposed, social-status-quo-reifying ending; and John Huston’s hothouse Carson McCullers adaptation Reflections in a Golden Eye (67), with Marlon Brando as a sexually repressed Southern Army major secretly lusting after Robert Forster’s studly, enigmatic private.

Brando’s assertion in Reflections in a Golden Eye that “any fulfillment obtained at the expense of normality is wrong, and should not be allowed to bring happiness,” seems to be the underlying message in much of mainstream gay cinema, hence their almost uniform unhappy endings. The idea that this changed significantly post-Stonewall is of course false. Many of our greatest out gay filmmakers hail from these repressive earlier generations, and thus bear the trace of stigma. These include the outspoken Terence Davies, whose most explicit, shadow-cloaked homoerotic imagery, in his shorts Madonna and Child (80) and Death and Transfiguration (83), seems right out of Genet, and who stated in a 2011 interview, “Being gay has ruined my life. I hate it. I’ll go to my grave hating it”—a sentiment that wouldn’t help get him on the cover of The Advocate. But to reject shame or ignore the stigma that persists is in its own way a form of intolerance, a means of invalidating “pre-Stonewall” lives. One doesn’t need to wallow in pity to acknowledge the difficulties of eras past. Whether gay films from the silent era through the ’60s—and beyond—express desolation or liberation, whether they implode with tea and sympathy or burst forth with fireworks and flaming creatures, they all embrace the melancholic as an essential part of our being. “Gay pride is a reverse or mirror image of gay shame, produced precisely against the realities it means to remedy,” writes Love; these films’ shared beauty exists in this contradistinction.

Blood of a Poet

The implicit, long-held sentiment that gays, by dint of being outside of heteronormative social progression, were doomed to failure was made more acute by the AIDS crisis, but this also led to definitive radicalization, in part because of the lessons of Stonewall. The New Queer Cinema that fully flowered in the 1990s can definitively, then, be called “post-Stonewall.” And if an era is truly demarcated by the attitudes that create it, then many pre-Stonewall films are, in spirit and action, post-Stonewall, and vice versa. This series reminds us that those floating in the liminal space between are most enticing. Take Jean Cocteau’s benchmark work of surrealism The Blood of a Poet (32), that visual poem-cum-physique pictorial, of animated statues, liquid mirrors, and deadly snowballs. It remains an emanation only of its own singular time and space, its erotic mischief beholden to no one and nothing but its own queered imagination. It is about repression and liberation, but only because any true work of art is.

IN FOCUS: The series An Early Clue to the New Direction: Queer Cinema Before Stonewall runs April 22 to May 1 at the Film Society of Lincoln Center.

Michael Koresky is a contributing writer for the Criterion Collection, co-founder and editor of the online film magazine Reverse Shot, and director of publications and marketing for the Metrograph theater in New York. He is the author of the book Terence Davies (University of Illinois Press).