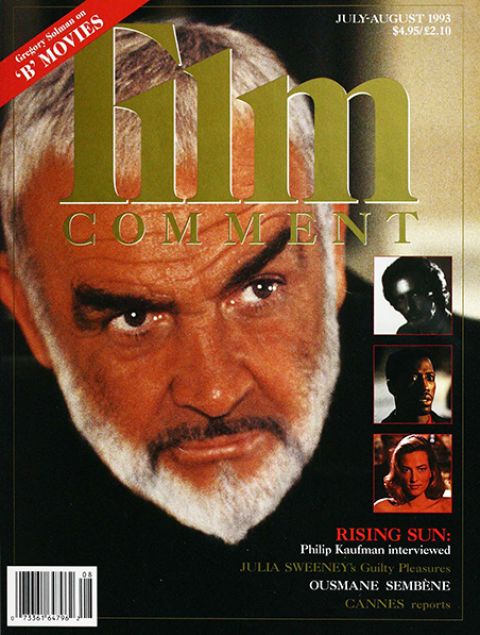

Ousmane Sembène: “We are no longer in the era of prophets”

Robert Lowell changed the face of American poetry with the admonishment “why not say what really happened”; no filmmaker anywhere in the world has taken such strong stock in that ruling principle as Senegal’s Ousmane Sembène, called too often (but not unjustly) “the father of African cinema.” His films make nearly all other modes of cinematic discourse seem decadent by comparison—cluttered with decorous images, imperialist indulgences, frivolous material, and a reliance on technical gimmickry to move audiences. The best of his work possesses a natural-born faith in the naked austerity of events, expressed via amateurish yet relaxed performances, a seemingly artless mise-en-scene, and a sense of Shaker-like utilitarianism. Camera movement is rare, closeups even rarer, and many of the images have the fading, overexposed tint of aging home movies. Whether it be famine, political upheaval, religious squabbling, or racial exploitation, things are as they are in Sembène’s world, presented with the demi-Catholic severity of Bresson, but with a distinctly African grit. Dead-serious just-so stories perpetually teetering on the fulcra of the basest human factors—greed, pride, fear, intolerance, etc.—Sembène’s modern folk art has all the power and glory of Old Testament mythos, while casting an ice-cold contemporary eye at the socioeconomic tarpit of African nations wrangling with their newfound independence and the crippling reverb of colonial control.

Like a flower’s tropistic bowing to the sun, the political cinema aesthetics of most cultures are predetermined in a virtually Darwinian sense by the culture’s particular legacy of oppression, colonialism, fundamentalism, protracted warfare, or will to power. Political movies can’t help but bring their social landscape to bear on their own form (just as cathedrals are really “about” the Crusades if you look closely enough). The first decade of Soviet filmmaking served the principles of Socialist control by way of propaganda calibrated with an almost trigonometric sense of manipulative purpose; whereas during the Second World War, the cinema of Allied nations used the tropes of dime-novel entertainment to stir the masses. Italian neorealism reclaimed its peasantry with the movies’ first willful cinema povera riff, encouraging the form of the films to reflect their subject; in the roiling Sixties, more restless South European filmmakers like Gillo Pontecorvo and Costa-Gavras began using the raw nerviness of in-your-face suspense thrillers for their post-mortems on local political wounds everyone else had hoped were long scabbed over. Agitprop documentaries, from Triumph of the Will to Shoah, all purport to be truth within their various subjective strategies, and can have, of course, notoriously mercurial and mysterious relationships to reality. JFK and Malcolm X, the most aggressive Nineties juggernauts of American political intent, do their frenzied dances to the tune of MTV editing rhythms and glowing Spielbergian power-shots.

Less powerful, and less wealthy, cultures have a habit of consequently paring down their films’ scope to the most basic of political realities: poverty, the vestiges of colonialism, the tangible meat & potatoes of class struggle. Third World cinematic traditions are therefore often and almost by definition politically structured, and guided like none other by the limited resources of filmmaker and subject alike.

Few oeuvres exemplify this hand-to-mouth politique as well as Ousmane Sembène’s. In contrast to Satyajit Ray, who began by making his Indian groundbreaker Pather Panchali without visible means of support and then went on to become revered grand master in one of the world’s most rapacious film cultures, Sembène still makes his dirt-cheap movies on the fly 30 years later, with found locations and actors, and for a poor, troubled culture whose regional cinema was, until recently, virtually nonexistent save for and a handful of contemporaries. Initially a renowned novelist in France, but with limited distribution in the francophone West African areas where the vast majority of people are illiterate and speak only native tongues like Senegal’s Wolof, Sembène switched to film in 1963 so that he could ostensibly engage in a direct dialogue with his countrymen; and indeed his films stray from the arid wastes of Senegal as rarely as Pagnol’s leave Provence.

Sembène has claimed to have realized the power of cinema upon seeing the defiant athletic prowess of Jesse Owens at the 1936 Berlin Olympics in Leni Riefenstahl’s Olympiad; typically, it was the images of the black Owens outracing Hitler’s übermensch, not Riefenstahl’s fabulously fascistic visuals, that caught his imagination. What’s most readily apparent in Sembène’s own films is his spare, ascetic approach to narrative, formulating tales with the same simplicity and straightforward moral identity as the fables related by village griots. That the rest of the world might be watching as well, and that Senegalese citizens often opt as we do for glossy Hollywood product over technically crude yet relevant local cinema, couldn’t come as much of a surprise to him. His adventurous life—student in Moscow under Mark Donskoi, WWII infantryman, longshoreman, labor leader, celebrated author—and work eventually circle back to the dusty, pragmatic verities of life in a Senegalese village, where the tribulations of clashing cultures are both universal and distinctively postcolonialist.

Borom Sarret (Ousmane Sembène, 1963)

A disarmingly simple, unmitigated day-in-the-miserable-life of an iconic Dakar cart-driver, Borom Sarret singlehandedly staked Sembène’s turf as a new and reckonable filmmaking presence, and at the same time claimed a place for sub-Saharan African cinema in the international gallery. Though not the first film to emerge from the region (Mouramani, from Guinea, appeared in 1953), Borom Sarret was the first to be widely screened outside of Africa; its seminal success at film festivals essentially force-fed the notion of an African cinematic topos to an early-Sixties movie world otherwise infatuated with the stylized hyperart of Antonioni, Fellini, Resnais, Bergman, et al.

Though only 20 minutes long, Borom Sarret sent epic-sized shockwaves through European film culture. That might say more about lingering postcolonialist culpability than the film itself. It’s difficult, today, to see what was so surprising; Sembène’s stripped-down style, tragic fatalism, and brutal take on class collision are such natural expressions of his nation’s mindscape that nothing short of recolonialization could’ve prevented it.

For all its formal modesty, the film is a harrowing, primitivist capsule of complex themes Sembène will readdress and explore in many later works. Neoneorealism and realpolitik soc-crit both, this mini-tragedy, wherein Sembène’s naïve and God-trusting Everyman keeps picking the black marble and loses everything because of societal barriers, the advance of modern life, and plain rotten luck, is built on dichotomies—a common Sembène strategy. Our hero-for-hire carts pregnant women and corpses both, and plies his trade in the fringe sections of the city, the narrow avenue between undeveloped villages and Dakar’s gentrified center, where peasants and donkey carts cannot go. Making hash of the traditional male warrior role on which African life was once centered, Sembène’s urban outskirts are littered with shellshocked vets of the culture war. In the end, the cart-driver having failed to supply food, his wife sets out bitterly to buy it via prostitution. “All I can do now is die,” Sembène’s dehumanized protagonist says finally in unemotional voiceover; the film’s Job-like ordeal cuts right to the core of perhaps Sembène’s most crucial j’accuse—the role of the new, black African élite in the decimation of their own nations.

The first sub-Saharan film to début at Cannes, the hourlong Le noire de. . . (Black Girl, ’65) is no less scathing in its encapsulated portrait of the colonialist instinct at work. Focusing on colonialism’s inherent racism, the scenario couldn’t be simpler: Diouana, a beautiful young Senegalese woman with no French (she narrates in Wolof), takes a job with a white bourgeois family in Dakar caring for their children. When they move back to France, she accompanies them and soon finds herself reduced to virtual slavery, with no days off and no contact with the outside world. (Explaining to a friend about Diouana’s silence, the wife asserts that “she understands instinctively, like an animal.”) If Diouana represents her people—Black Girl is nothing if not overtly metaphorical—she also represents their unconscious urge to follow the withdrawn colonialism home rather than have to reinvent themselves as free citizens. When the mounting tensions and suffocating anomie end in shocking, silent tragedy, Black Girl takes on the aura of minimalist manifesto—a salient, albeit pitiful, precursor to the spirit of Thelma & Louise as much as Do the Right Thing.

As Sembène himself has pointed out, his cinematic statements owe less to romantic notions of “negritude”—which by definition subtracts degrees of responsibility for the state of West African disarray from colonialists—than to the hard, gimme-food-and-shelter truths of quotidian living in Senegal, where blame falls squarely and without ambiguity upon the oppressive powers that be, black or white. Scarcely any other filmmaker attests so eloquently to the integrity of native experience; as Jay Leyda has said, no mere visitor to Senegal could have come to Sembène’s seemingly de-aestheticized formal conclusions.

His true feature début, Mandabi (’70), is a virtual comic flowchart of the traditional tribal world lost in modernday red tape; it simultaneously maintains a quasi-Biblical candor and evokes the spiraling nightmare of Steinbeck’s The Pearl. Here, literacy, self-perpetuating bureaucracy, and Western systems of control are the new, black, Frenchspeaking petit bourgeois’s methods of sustaining power over the illiterate majority. Sembène paints it all in broad, symbolic strokes: the anonymity of Dakar and its various institutions signify bureaucratic entropy on a continental scale.

The hero, Ibrahima, is a vain, blustery Muslim living with two wives in the semi-developed Senegalese ‘burbs. When he receives a money order (mandabi) from his Parisian nephew, the mere news of it drowns him in false friends, harrowing debts, and much woeful interfacing with the city’s indifferenc corruption as he attempts to cash the cursed thing, and repeatedly plays the sucker to modernity’s more usurious elements. Sembène’s films rarely end in any manner but disaster, and Ibrahima’s saga has an inexorable, Aesopian logic in which misfortune is the true wage of fools. Ibrahima, like other Sembène characters, has little depth and doesn’t need it—he’s a nearsighted, puffed-up Fred Flintstone in a world where water must be bought and a bag of rice makes for a luxurious feast. The nuances of his character are less important to Sembène’s scheme than the character of the system that strips him of worth and dignity; Ibrahima is the representational peasant-pilgrim in the New World of the postcolonialist bourgeoisie, and as such need be nothing more than recognizably human, with ordinary human failings.

Emitai (Ousmane Sembène, 1972)

Mandabi was perhaps Sembène’s earliest wholehearted interrogation of the self-governing Senegalese social system; it was complemented soon after by Tauw (’70), a short postrevolution, pre-Generation X statement focusing on the dehumanizing relentlessness of dumb low-wage labor and a literal no-futurism for the West African youth culture that makes punk politics look like one long spoiled whine. With Emitai (’71), Sembène began exploring other manifestations of historical injustice—here, the exploitation and abduction-draft of non-nationalized tribesmen by the French during WWII. As in the dour pageantries of Miklós Jancsó and the Leninist firecrackers of Eisenstein and his confreres, Emitai has no primary characters, just masses of social force. It is Sembène’s deceptively casual sense of spatial anxiety, dividing our attention between the besieged village’s ground zero and the “hidden” circle where the village’s men endlessly debate about their situation, that controls the action.

Opening with a thrilling guns-vs-spears battle scene (in which white officers lead black soldiers against their own countrymen) that stands as Sembène’s All Quiet on the Western Front, Emitai is a classically clearcut, de-exoticized vision of African culture routed out and mauled by European needs. A lone desert tribe among many, the Diola are besieged by French wartime forces set on first kidnapping the tribe’s young men at gunpoint for infantry service (“You have volunteered,” the officer tells them; “you will have great war stories to tell your grandchildren”), then looting the weary village of its rice supply. Yet Sembène fastidiously resists a Manichean view of the matter: The elder Diola men hide themselves from the invaders and bicker endlessly about what to do—eventually deciding, several times, to sacrifice chickens to the god Emitai—while the women more pragmatically hide the rice and confront the troops as a veritable wall of passive resistance. Neither are the French authority figures ever evil or all-powerful; rather, on the exhausted edges of the Eastern Front, they’re tired and halfwitted, their positions transitory and makeshift. This powderkeg situation is only complicated by the appearance, and influence, of Emitai himself, plunging Sembène’s usually pragmatic social universe into the sky-high mythos of Indian masala movies. It ends, inevitably, in an appalling assault on all things Afrique that recalls several martyred waves of post-Stalinist Eastern Bloc cinema. A perpetual motion machine of ethical ambiguity and confrontational tension, Emitai explores and redresses recent history from a Senegalese perspective—a strategy that would continue in Camp de Thiaroye (’87).

A raw, subtle epic excavating yet another forgotten episode of downhome horror from WWII, Camp de Thiaroye is the first pan-African feature produced completely without European technical aid or co-financing; it took nearly 30 years, but with this Algerian-Ibnisian-Senegalese co-production West Africa can truly be said to have its own film industry.

Thiaroye‘s historical imperative revolves not only around its protagonists’ tragic fate at the hands of the French, but their very existence as history. What actually happened at Camp de Thiaroye in 1944—purposefully suppressed in all quarters for years—could be read as an abstract of colonialist friction; it conforms so expressively to Sembène’s themes that one could be tempted to suspect he fashioned it from whole cloth. But, as always, the film’s sober relationship to how things were (are) remains Sembène’s polemical crux.

Camp de Thiaroye centers on the Senegalese infantrymen who returned from the war expecting to be repatriated to their individual villages; they were instead sequestered in a transit camp. We see them made to feel more like POWs (several are Buchenwald alumni) than victorious soldiers. As the voltage between the dispirited men and their French guards rises, culminating in the seizure of the camp by its prisoners, reconstructed history lesson takes on the bitter menace of the familiar Great Escape prison-camp genre feeding upon itself like a cancer. It climaxes in a massacre—dated in a title, NOV. 30, 1944, 10 HOURS—which Sembène portrays with a hellish brio that’s as close as he’s ever come to hyperbole.

Like Emitai, Camp de Thiaroye is an ensemble piece in which each character occupies his own point along the sociopolitical scale stretching between conformism with the oppressive powers and unbridled revolution. (The cultured Diola sergeant, who at first enjoys the privileges of his rank and later represents the rebellion at its most ferocious, tells Emitai‘s village-slaughter story as his own, indelibly connecting the films as the first two-thirds of a WWII trilogy begging to be completed.) Ultimately, however, the outrage of Camp de Thiaroye, though inherent and powerful, seems to preclude the gray-shaded dualities that make Sembène’s other films so rich. Ceddo, Xala, and Guelwaar are all more eloquently shaped as colloquies.

Ceddo (’76) is Sembène’s only attempt to visualize and thereby reinvent pre-Christian and pre-Muslim African myth (a subgenre of African filmmaking that has since exploded). It is also his only film to center on a strong woman—a textual aspect to his work that in the end reflects more about the postcolonialist culture than about the artist.

Set in the 17th century, on the cusp of the slave trade, Ceddo focuses on the religious patterns of power that threaten to tear a village apart. Traditionally matriarchal, the villagers are divided between ceddos—adherents to the ancient myth system—and Muslims, who along with the relatively peripheral influence of a Christian missionary engage in a now-familiar brand of fundamental intolerance for the paganish ways of yore. A frustrated ceddo kidnaps the village’s proud princess and holds her hostage in order to inspire an ideological critical-mass among the village’s leaders: the king, his opposing sons, his daughter’s suitors, and the imam himself, who is positively Ayatollah-ish in his bloodthirsty fervor for fatwas and forced conversions.

As in Emitai, Sembène adeptly demarcates the mounting tensions between two spaces: the village’s central meeting ground where the king holds court, and the wild patch of scrubland where the ceddo holds the indignant princess, who refuses to be bound up and instead acknowledges a single length of rope stretched in the sand as the border of her imprisonment. Sembène takes great pains to construct his story by way of the formal injunctions of ceddo society—the roles of griot and royal spokesman as middlemen in tribal exchanges, the manner by which champions are chosen to rescue the princess—and Ceddo has the ceremonial air of a Greek tragedy, complete with bloody finale (in a bracing fit of prairie justice, the princess takes the imam out) and timeless aphorisms (“If a lizard teases a turkey it’s because there’s a tree nearby”). Ceddo also harbors a handful of Sembène’s most arresting images: a goat running horrorstruck through the flames of the burning village; the seminude princess lounging in the desert dust; a dead man frozen in a crouch position and buried by his neighbors in a giant mound of dirt, the tip of his bow jutting from the top as a marker.

Xala (Ousmane Sembène, 1974)

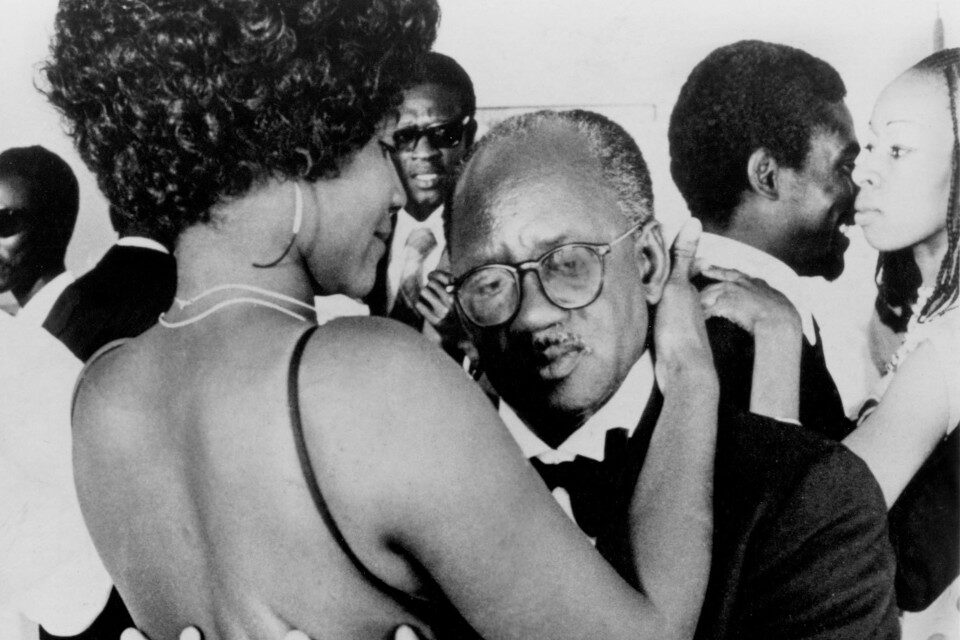

Xala (’74), at the other end of the aeon, is an uproarious comeuppance comedy set in contemporary Dakar and lampooning, once and for all, the new Senegalese ruling class’s adoption of Eurogreed—El Hadj, the film’s affluent demimonde joke-butt, even insists his chauffeur-driven Mercedes be washed with Evian. Sembène opens with a revolutionary mock-allegory preamble wherein Senegalese blacks storm (dancing) the Chamber of Commerce, eject the white officials and various symbolic objects of their régime out onto the building’s front steps, and install a “pure” Socialist government while simultaneously receiving briefcases packed with cash. The biting irony of Xala is Sembène’s broadest, and all the more arresting for his starkly lit, mock-doc visual style (it’s a world without shadows), which often leaves us second-guessing what was a joke and what wasn’t. As with nearly all his films, the division between classes is limned by language: when the new leaders address their Wolof-speaking public, it’s in French—”We have chosen socialism, the only true socialism, the African path to socialism, socialism with a human dimension”—happily indulging in the blithe, straight-faced corruption practiced for so long by colonialists just before climbing into their limos and taking off.

“Xala” is Wolof for the curse of impotency, which is inflicted upon El Hadj on the eve of his third marriage by mistreated beggars. Taking on three wives is in itself both a pathetic display of masculine vanity and a Senegalese extravagance on par with getting a second beach home in Malibu; El Hadj’s impotence is Sembène’s most incisive metaphor for his nation’s economic vice and class-conflicted inertia. “You’re not a white man,” one of El Hadj’s mothers-in-law tells him. “You’re neither fish nor fowl.” As he tries to rid himself of the xala by visiting rural village marabouts (medicine men), one of whom he angers into reinstalling the curse by paying with a rubber check, El Hadj is revealed as a distillation of capitalistic tendencies who made much of his fortune by diverting supplies meant for famine-struck areas. Fittingly, the news of his impotence brings about his bankruptcy.

Easily the most comical of Sembène’s films—in the wedding-night shenanigans, it becomes refreshingly ribald—Xala has several separate currents of thematic action that collide in its final, chillingly unfunny moments: the disenfranchised, Hogarthian beggars return to El Hadj’s home, ransack it, molest his first wife, and offer El Hadj the only permanent cure for the xala—to strip naked and be spat upon, to which he eventually consents. This rite of humiliation, appalling in its visceral impact (and predating Todd Haynes’ Poison by some 16 years), is presumably Sembène’s symbolic answer to the plague of greed and exploitation independent West African nations have inflicted on their own: the ritualistic destruction of dignity as a process by which to tear down divisions of class. Xala‘s satire turns on a dime in this last scene, and lays bare the suffering of Sembène’s people in a way the film hadn’t prepared us for. It’s a textual Venus-flytrap, luring us into the maw of honest sociopolitical pain.

Sembène’s newest film, the lean and eloquent masterwork Guelwaar (’92), takes the religious battlements of Ceddo into the 20th century, where the isolationist mania of both Christian and Muslim coalitions reaches a nadir in the drought-stricken badlands of Senegal. The title character is a radical, anti-interventionist activist assassinated before the film begins: we see him intermittently in flashback, amid stirring Malcolm X-ish speech scenes. On the morning of his funeral, the mourners discover that his body’s missing from the morgue, and all hell breaks loose. There’s ghastly talk of the body being stolen by fetishists, among a great many other wild theories, while sharp comic points are scored off Guelwaar’s eldest son, who’s become a superior-minded French citizen, and Guelwaar’s long-suffering wife, who has her own personal wake kneeling before her troublesome husband’s empty suit: “Our next meeting will be tense,” she says dryly. Soon it is discovered that the remains of Guelwaar—a baptized Catholic—have been mistakenly buried in the local Muslim cemetery, a bureaucratic gaffe that leads to a direct confrontation of faiths. While Guelwaar’s family naturally wants to relocate the body in consecrated ground, the Muslims maintain no mistake was made and even the mere presence of infidels on their holy turf would be blasphemy punishable by death. This imbroglio’s every intolerant wart is backlit by Sembène in his most perfectly realized scenario, as the two congregations eventually face off in a riot-to-be stemmed only by a helpless constable negotiating the literal, and ideological, middle ground of the graveyard, overlooked by looming high-tension towers.

Sembène again conceives his dozen or so main characters (only two played by experienced actors—the rest simply live in the village) as embodiments of social energy, and structures his drama spatially: the two camps bicker over a patch of arid desert of no inherent value and no meaning beyond that which is arbitrarily imposed upon it. And if any character of Sembène’s could be said to wholly represent the filmmaker’s political viewpoint, it’s Guelwaar, the agent provocateur himself, whose only dogma was the ideal of a unified Africa unsundered by petty religious squabbling, bureaucratic chaos, and class combat, and who went so far—as Guelwaar itself does—to condemn the African nations’ reliance on “emergency aid” from other countries, Sir Bob Geldof or no Sir Bob Geldof.

In Guelwaar’s radical climax, after the successful reburial of the eponymous corpse, a truckload of food is overrun and destroyed by villagers as per Guelwaar’s last public entreaty, seen in flashback. Guelwaar draws the graph of Senegal’s currently raging Christian—Muslim civil war in miniature, much as Jan Némec’s 1966 Report on the Party and the Guests dissected the clockwork of Soviet totalitarianism through the invasion of a small outdoor party by oppressive, and wholly symbolic, forces. “We are no longer in the era of prophets,” Sembène said at a recent Lincoln Center screening in honor of his 70th birthday, and though his film’s wrangling occurs mostly on sacred ground of one type or another, the terminal decimation of the supply truck brings us right back to the scorched-earth issue of economic independence and equality—Sembène’s thematic sine qua non, and indeed the basic brick of all political cinema. If a film won’t matter on a fundamental level to his countrymen, as films rarely matter here, Sembène won’t make it. Questioned about the shiftings of his politics through the years—the barrel of his interrogatory camera leveled at colonialists, fundamentalists, bourgeoisie, and aspiring peasants in varying proportions—Sembène answered: “It’s not me, it’s my people that evolve. I live among them; I’m like the thermometer.” Quite possibly the only filmmaker left in the world who cannot be bought and sold, Sembène represents the dying heritage of political films still possessed of a virginal faith in social change, a faith not in films for profit’s sake or even film’s sake, but for man’s sake.