On Earth as It Is in Heaven: Ermanno Olmi

It’s strange that so few directors in Italy are religious, at least in the sense that their films are imbued with signs of their faith. Though they share real estate with the Vatican—or maybe because of its very proximity, on the theory that familiarity breeds contempt—Italian filmmakers are much better known for political militancy than religious fervor. Among the few exceptions are Roberto Rossellini and, in a complex way, Pier Paolo Pasolini. And most emphatically, Ermanno Olmi.

When we met in Rome to talk about his films, it was the Epiphany, the last of the Christmas holidays. The 69-year-old director and his wife, Loredana, had just dragged themselves back to their hotel from the end-of-Jubilee closing of the Holy Door at the Vatican, where millions had stood in line for hours to receive an indulgence. As the director of a papal biopic, he was on familiar turf.

The sacredness of life, the dignity of work, and man’s search for the highest spiritual values are themes that deeply color his 14 features and later documentaries. It’s as impossible to look at Olmi’s films without taking his Christianity into account as it would be to rub religion from the work of Krzysztof Zanussi, his Polish contemporary and friend. Note, he’s also far from the mystical-supernatural current of films like Breaking the Waves and American Beauty. Olmi has the earthy consciousness of an organic farmer, one who disdains pesticides, plants by the moon, and thanks Providence for an abundant harvest. There is nothing mystical about his brand of callus-handed Christianity, with its love for all creatures great and small and particularly man in all his defects.

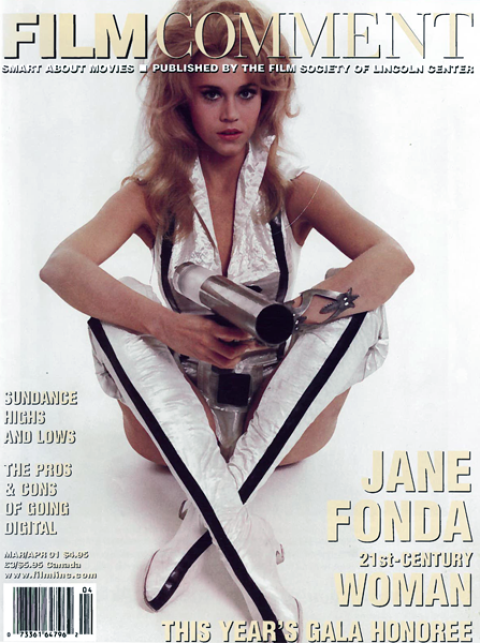

The Profession of Arms (2001)

In this and other ways, Olmi’s whole career is an anomaly on the Italian scene. Living in self-imposed isolation in the Dolomites high on the Asiago plateau, not far from his native Bergamo, he remains deliberately outside the ebb and flow of Italian film culture (admittedly not the most exalted in recent decades). A family man and hermit who, like Lars von Trier, shudders at the idea of setting foot on a plane, he keeps no videocassettes of his films, no set photos, and begins rare interviews with the disclaimer: “Cinema is not my life. Living is.”

His new film, The Profession of Arms, will be released in Italy in March. A bloodcurdling historical epic about the invention of the cannon, it is vehemently anti-war. Ipotesi Cinema, the utopian film school based on alternative production methods that he founded in the mountain town of Bassano del Grappa and has directed since 1982, is taking new directions, but its many alumni—including directors Francesca Archibugi, Giacomo Campiotti, Maurizio Zaccaro, and Isabella Sandri—still call on him like “a father” to keep him abreast of their new projects.

In Italy, the critics have begrudgingly admitted that Olmi is a major director of his generation, adding points for his supposed “peasant” origins, and subtracting them whenever his faith became explicit. The Tree of the Wooden Clogs (1978) was flogged for its Catholic-populist vision, which supposedly idealizes resigned humility in the face of oppressive power. One admirer of The Legend of the Holy Drinker (1988) couldn’t help holding his nose at “the smell of the sacristy” it exuded. But this is a nation chock-full of religious complexes.

A Man Named John (1965)

It’s not that Olmi is seen as a director who lacks a social conscience; it’s that his films resolutely sidestepped social outrage and analysis when all around him filmmakers were waving flags from the front line of social commitment. True, two of his least successful pictures take religion as their subject, A Man Named John (1965), a dutiful biography of Pope John XXIII narrated by Rod Steiger, and Keep Walking (Cammina Cammina, 1983), an uninspired view of the Three Wise Men on their way to Bethlehem. But once he steps away from recounting Christianity and allows it to function in the background as unverbalized metaphor, he hits his stride.

The early documentaries, made in-house for the electric company Edison Volta, reveal how intimately familiar Olmi was with working-class life in the Fifties. He captures the spirit of transformation that was shaking the country as it walked the path to industrialization. This becomes a key theme in films like One Fine Day (1968), where the values of rural society disintegrate in his portrait of a Lombard industrialist who accidentally runs over a man in his car, and The Tree of the Wooden Clogs, which poignantly sings the swan song of an Eden-like harmony between man and nature.

The pleasure to be found in watching Olmi’s work today lies in its undiminished depth and mystery. In his never-ending effort to get under his characters’ skins, Olmi recalls Nana’s instructions in Vivre sa vie: “A chicken is an animal composed of an inside and an outside. Take away the outside and you get the inside. Take away the inside and you get the soul.” Olmi is out to photograph that soul.

The Tree of the Wooden Clogs (1978)

Those Olmi faces. They remain unforgettable, even years after seeing them: the Kafkaesque victimhood of the office boy in Il Posto (The Job, 1961), the angelic roundness of the peasant-bride in The Tree of the Wooden Clogs, the petrified mask of evil of the Lady in Long Live the Lady! The Legend of the Holy Drinker. He has always preferred non-professional actors. Their unguarded gazes and non-acting, at least in his hands, allow a clearer view into their inner nature.

From the beginning, Olmi made observation into a moral principle. For a feature-length documentary Edison Volta designed to plug the efficiency of the company’s guards at its big mountain dams turned into his first fiction film. Time Stood Still (1959) is the first of a trio of black-and-white pictures that remain among his finest work. Time Stood Still is the purest of them all and the one most strongly influenced by neorealism. Time loses its workaday connotations up in the mountains, where it’s just man and nature, immortalized in the image of a boy tossing himself playfully into a heavy snowdrift and leaving cookie-cutter outlines in the snow.

But eventually even Olmi’s characters have to face up to city traffic and a day at the office. Il Posto is a definitive look at the plight of office workers, lambasting their busy do-nothingness with killing comprehension. As wistfully comic in its straight-faced way as Chaplin’s Modern Times, it foretells the inhuman new world being ushered in by the economic boom of the Sixties.

Time Stood Still (1959)

At 15, bashful Domenico ventures from his family’s semi-rural home on the outskirts of Milan to try out for a job with a large, impersonal firm in the city, his mother wishing him “a secure job for the rest of his life.” Ugh. He drags himself past a horse-drawn cart and farm equipment, almost missing the train for his big interview. There, in the company of 20 other hopefuls, he submits to an excruciating but hilarious “psycho-technical exam” that includes demonstrating a knowledge of arithmetic and an ability to flex the knees.

Doing his own camerawork, Olmi crisply conveys the spic-and-span shine of bureaucratic glass and the pompous medical-educational atmosphere spun like a web around the applicants. With his farm boy naivete, the preternaturally serious Domenico is a fish out of water (a metaphor visualized in the film) who throws himself into adapting to his “exciting” new environment. As spectators we see through the company’s phony paternalism; why, then, do we find ourselves cheering for the assistant doorman’s promotion to a pool of paper-pushers?

After courting a pretty girl who applies with him, then losing sight of her because the company assigns them to different buildings and different shifts, Domenico watches his love life definitively collapse at the company’s New Year’s Eve party, a climax of horror that makes The Fireman’s Ball look like a Hollywood bash. Tempering Forman’s cruelty, Olmi ends the interminable evening with his characters truly enjoying themselves. Talk about turning a scene around! This is very slow cinema, one of the director’s most demanding traits; but for those who can sit through it, its ruthless portrayal of life in the tortoise lane is devastating.

The Fiancés (1963)

By his third film, The Fiancés (1963), Olmi begins to pull away from a head-on documentary look. The editing is much less linear, looking forward to the smoother use of fragmented structure in The Circumstance (1974), where parallel stories reflect a family’s disintegration. Stuffed with flashbacks, flashforwards, dreams, and memories, The Fiancés is curiously disjointed, as though Olmi still had misgivings about introducing characters, acting, and a story line.

Through Giovanni’s eyes, we see the sunbaked Sicilian world and its local customs. Olmi contrasts the inhuman scale of the steel plant, typically shot from high cranes, to soulful snatches of nature: windmills, the sea, fields stacked with cones of salt, a sudden storm.

Not surprisingly, the film champions the rhythms of nature and man over the artificial work-time imposed by heavy industry. The last shots, showing children staring in awe at a downpour while Giovanni regrets having to go to work on such a day (it’s even Sunday, so the Lord’s agin’ it, too), flash us forward to The Tree of the Wooden Clogs and its peasant wisdom that outlaws work when it’s raining.

The Tree of Wooden Clogs (1978)

Ironically, The Tree of the Wooden Clogs, Olmi’s international breakthrough, was originally made as a three-hour, three-part TV series, but went on to win the Palme d’Or at Cannes in 1978. This tale of peasant survival in late-19th-century Lombardy is understandably considered his masterpiece. It is certainly a case of the right director meeting the right material, over which he had nearly total control (as in his previous work, Olmi also shot, edited, and wrote the film).

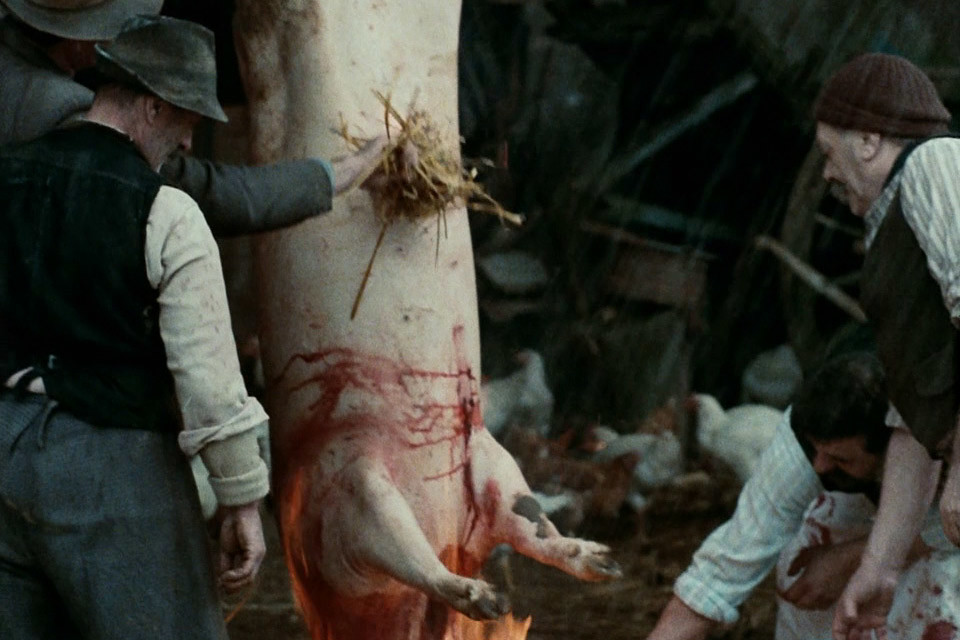

The illusion of recapturing lost time—here, the misery, hard labor, simple joys, and natural rhythms of the peasant, world—has rarely been more convincing. We watch the opening hour for the sheer beauty of the shots, its simplicity, humility, and quietude. Returning to the documentary techniques he used to such great effect in his first three films, Olmi virtually eliminates characters and dialogue. His camera darts randomly among four families who live in a sprawling farmhouse belonging to a rich landowner. Little better than serfs, they till his fields and raise his livestock, and hand him two-thirds of every lira they earn. We watch them doing the field work, singing songs, killing a goose, butchering a hog, husking corn, and washing clothes in the river as babies wail in the background.

Where in 1900, Bertolucci gave the padroni the familiar faces of Robert De Niro and Dominque Sanda, in Tree we barely glimpse the man who holds the power of life and death over these sons of the earth. Olmi’s maximum comment on the landowners is to associate them with opera and chamber music; the peasants he identifies with the sublime J.S. Bach. The fast cutting and initial lack of close-ups keeps them from emerging as individuals until the film is well advanced. They are literally part of the landscape. We feel their closeness to nature—the moon, snow, rain, the earth, the changing seasons. Even a boy’s chaste courtship of a girl takes place on the road, in the midst of nature. When he asks for a kiss, she tells him they must “wait for their time.”

The Tree of Wooden Clogs (1978)

Tree exalts two social institutions, the family and the church, as the containers of moral values. Like Bach’s music, the bells that ring throughout Olmi’s film seem to come directly from heaven. God is watching over these simple folk. Viewers allergic to Christianity are advised to review Breaking the Waves.

The film’s great and undeniable religious intensity was considered “reactionary” and “mystifying” by some Italian left-wing critics. They accused Olmi of being an apologist for an unchanging natural world and an enemy of modernity, but I think that, whether the director intended to or not, the film makes us understand why that natural life had to end. The offscreen cruelty of the final scene forces the viewer to supply the missing piece. What in the world is going to happen to the displaced family of Minek, the boy with the wooden clogs who dared to go to school? Good-bye farm idyll; we want a revolution and we want it now!

Great social uprisings hover in the background of Maddalena and Stefano’s wedding trip to Milan. A ripple of fear empties the street and for a moment we think they’ll be trampled underfoot by the Italian army, busy repressing popular unrest. Instead, Olmi leaves this future shock off-screen, noting its presence but perhaps unwilling to face it himself. The two innocents spend their wedding night in a convent, where they receive a gift of Providence: a baby orphan whose annual endowment will save them from poverty. This wild narrative invention, a throwback to penny novels (or to classical Lombard novelist Alessandro Manzoni), is one of the most spookily moving scenes in all of Italian cinema.

The Legend of the Holy Drinker (1988)

Gifts of Providence return in The Legend of the Holy Drinker, based on a marvelously concise novel by Austrian writer and renowned alcoholic Joseph Roth. Olmi stretches the story into a rosy-hued, over-long, but still captivating movie. It is the closest he has come to making a card-carrying European art film. Part of the explanation for its less artisanal look is health-related: a chronic viral infection that first struck him in 1984 and which has made it increasingly difficult for him to continue working as a one-man film crew. In Drinker for the first time he uses a professional actor and hands the camerawork over to Italian cinematographer Dante Spinotti.

Though it shamelessly tugs on the heartstrings, the story is so mysterious that it delves beyond surface emotion to something deeper. Andreas, an alcoholic Polish miner who sleeps under the bridges of the Seine, one day receives a gift of 200 francs from a mysterious benefactor. He asks only that Andreas repay it, when he can, to St. Thérèse of Lisieux, the “little saint” whose church is Holy Mary of the Batignolles. Andreas may be a bum, but he is a man of honor and insists he will repay his debt. Circumstances, and his own weak will, keep preventing this from happening.

The pleasures of the film are many. They include the slow reach of hands for money (Olmi has never been more confident in letting images tell the story instead of words), a ballroom shot like a cathedral, a heady succession of miracles, Hauer’s dignified, all-too-human drunk, and an uncanny use of Stravinsky’s music to give the story a thousand different moods. The film also contains what arguably may be the best representation of a saint on celluloid. Ambiguity is naturally the keyword: is all this really happening?

The Legend of the Holy Drinker (1988)

The film ends with Roth’s inscrutable epitaph: “God grant all of us drinkers such a fine and easy death.” As Olmi glosses it, “If I think of the moment when I, like everyone else, will have to add up the credits and debits in my ledger, I’d like that moment to be so sweet and easy that I don’t even notice I’ve paid my debt.”

In Olmi’s world, that debt is love, and those who give a gift of love are saved. The forms of love—friendly, maternal, sentimental, erotic, platonic, spiritual—blend into a single sacred thread running through all his characters. It is the give-and-take by which they relate to each other and reach out, unconsciously, for their salvation. From the plucky student in Time Stood Still to Johannes De Medici, the noble warrior in The Profession of Arms, it girds them with a core of values that no landlord, employer, or war can shake. It’s what makes them human and, in the last analysis, invincible.