Olaf’s World: Nigerian Videofilm Culture

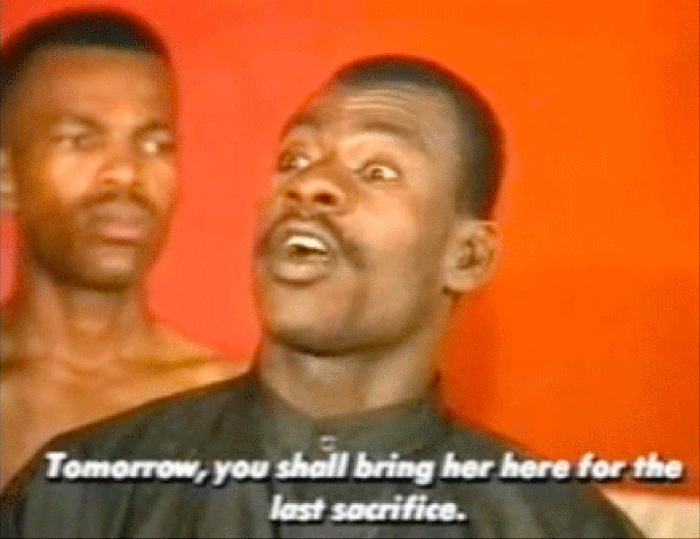

If true trash-culture connoisseurship still existed, Nigeria’s videofilm industry would have long since become a major object of cinephilia. Absurdly ardent acting, the absence of anything remotely resembling craftsmanship beyond keeping the actors in frame (forget focus), dialogue-drowning soundtrack noise, sub-amateur-porn production values, and, above all, as in Excursions into Hell and Angels Saving the Day, ultra-twisted stories featuring, on occasion, money-spewing mummies (did I mention the gloriously ridiculous special effects?) and always ending with a moral so heavy you would need a crane to lift it: Nigerian videofilms should have been the next big thing. Strange as it seems to Western eyes, much of the above actually makes perfect artistic sense within its cultural context, although many in the industry would be more than happy to improve the technical standards of their productions.

Unsurprisingly, the Francophone African film establishment—the movers and shakers on the continent and their (often self-appointed) ambassadors in the world at large—have shunned this staunchly English-speaking cinema on the grounds of good taste. Officially they’ll say they’re only interested in works shot on film. But what they really mean, setting aside the thorny question of Third Cinema, is that they disdain the Nigerian videofilm industry’s crass commercialism. Give or take a minor masterpiece or two, nothing could be further from wholesome art cinema, with its healthy messages and clean-cut images, than this lurid West African smut, dedicated to making money hand over fist. Not to mention the fact that videofilms result from a confluence of noncinematic influences seasoned with disreputable movie ingredients from as far afield as Hong Kong, Mumbai, Rio de Janeiro, and the lower strata of Hollywood—hence anathema to traditionalists and purists. Some regard the industry’s rapid growth, without any outside (i.e. Western) support, as a snub to well-meaning ex-colonial paternalists.

Just like the various forms of Indian popular cinema, the narrative strategies employed by Nigerian videofilms are a world away from Western norms. If Bollywood has only now become a part of film festival discourse—when has a Mani Ratnam film ever gone head-to-head with Uncle Jean-Luc in a festival competition?—what chance that Nigeria’s stories of demons and witches and the power of money and love will make it into the major leagues, technical problems aside?

Thunderbolt

After just over 10 years, the videofilm industry—based in the southern half of the country—now churns out roughly 600 titles annually, making Nigeria one of the world’s top film-producing nations. The notion of an African Bollywood—half-jokingly called Nollywood—is suddenly catching on. And the videofilm has begun to turn up on the margins of the Western festival scene. This year, Berlin hosted a two-day fringe event of discussions and screenings devoted to the Nigerian videofilm industry, while the Rotterdam International Film Festival presented a tribute to Yoruba auteur Tunde Kelani, who is generally acknowledged as the industry’s leading light.

In fact, Kelani is an atypical figure. Trained as a cinematographer in the Seventies, he’s one of the few real filmmakers in the videofilm business (most of its entrepreneurs are local businessmen by profession, video store owners and the like)—and one of the only ones familiar with celluloid: a quality-conscious videofilm auteur, an artist of ambition as well as talent.

Rotterdam’s retrospective was nonetheless indicative of a certain wariness toward videofilm culture. The festival presented only three of his seven features: Thunderbolt (01), Kelani’s melodrama about tribal tensions and the conflict between different schools of medicine (Western vs. African), and two parables of corruption and the abuse of power, Brass Jingle Bells (Sawaroide, 99) and its sequel, The Gong of Taboo (Agogo Eewo, 02). Neither is terribly representative of the videofilm norm, which usually shies away from direct political engagement and whose major productions—such as Kelani’s I Want Happiness (Ayo ni mo fe) I & II (96) and The Land Belongs to the Gods (Ti oluwa nile) I—III (97)—present, at their best, a realistic picture of Nigeria’s mores, customs, and social problems.

Made as much for theatrical screenings as home video use, these productions often run to six hours and are released in two or three feature-length installments every three months or so. (Sawaroide and Agogo Eewo were made years apart: the first in reaction to Nigeria’s military dictatorship, the second one as an expression of hope for the new democracy.)

Ajani Ogun

The form’s origins lie in the Seventies, when Nigeria was struggling to define an autonomous film culture. The major auteur from this period was the versatile Yoruba Ola Balogun, a graduate of the IDHEC film school in Paris, who tried his hand at a variety of approaches, from populist and genre work to art cinema. He also experimented with making films in some of Nigeria’s main dialects (Yoruba and Igbo), but he discovered that for a film to have a wider appeal it had to be dubbed (widespread illiteracy precluded subtitling, though today it’s occasionally done with important works to expand the viewership) and couldn’t be too specific to any of Nigeria’s subnational cultures. Balogun took several unsuccessful stabs at creating crossover films by tackling “larger” subjects, such as a Nigerian’s search for his family history in Brazil in Black Goddess (A Deusa negra, 78), or a group of African freedom fighters struggling against colonial oppression in Cry Freedom (80).

Balogun’s first major success was Ajani Ogun (75), based on a popular Yoruba traveling-theater piece by Duro Ladibo. Other major traveling-theater producers (usually writer-director-actor-entrepreneurs), like Hubert Ogunde and Ade Folayan (aka Ada Love), followed his lead, and a Yoruba traveling-theater film culture blossomed. The subsequent success of Balogun’s witchcraft thriller Aiye (79), based on a play by Ogunde, transformed this emerging cinema by spawning a whole new horror subgenre. (Today, almost all videofilms contain horror elements, some of them extremely graphic. In this cinematic universe, humans and otherworldly beings actively consort with one another.) Yoruba traveling theater adapted. Some producers began incorporating film and, later, video into their shows, occasionally with spectacle-laden SPFX finales. They also diversified their work by realizing it in multiple media—as stage productions, TV series, and movies, first on 35mm, then on 16mm, and eventually on video. Yoruba traveling-theater audiovisual culture is the missing link between Nigerian cinema’s celluloid era and today’s videofilm culture.

Balogun and other directors from that period faced one big final problem—distribution. Filmmakers usually had to self-produce and -distribute, and a real network for the presentation of Nigerian films never developed. In some ways, this meant that it made more sense to produce films on a regional rather than national basis. It’s not surprising that the videofilm industry was created mainly by distributors, who saw the commercial potential and organized their filmmaking resources accordingly. The widespread street violence and curfews of the Eighties had already made cinema-going virtually impossible, and watching tapes at home was a safe way to spend the evening. Moreover, a local-theater video culture had already been established, featuring taped Hausa drama-group performances and short comic Igbo sketches, a kind of AV spin-off from Onitsha market literature, the other important indigenous influence on Nigerian videofilm culture.

Living in Bondage

Yoruba traveling-theater cinema is but one genre or idiom among many. In the celluloid era, there were two main film-producing cultures: the Yoruba in the south, where the emphasis was on popular cinema, and the Hausa in the north (particularly filmmaker Adamu Halilu), with its more art-house-oriented, semi-spiritual cinema attempting to reflect Islamic beliefs. In the videofilm era, the Igbo became the industry’s main players, by not only creating an Igbo cinema but also controlling a large part of the English-language industry as well as parts of the Yoruba business. Tapes and home entertainment for the whole family suited cultural preferences, family values, and the Igbo work ethic. While the Yoruba still stick very much to traveling-theater culture, the Igbo take their cue from Hollywood genre material, and the Hausa, in many ways a culture apart, from Bollywood weepies.

Combining elements of traveling-theater film, telenovellas, Bollywood, Hong Kong, and Nigerian theater and TV (with their professionally trained actors), videofilms are strange and fascinating hybrids. In a sense, even more than Bollywood films, they’re an open form, an organism capable of incorporating anything interesting that comes its way while also transforming everything it touches. Even Kelani’s most sophisticated projects, as well as those of videofilmmakers like Zeb Ejiro, Tunde Alabi-Hundeyin, and Tade Odigan, are filled with elements that work against each other. As a result, narrative rhythm is often erratic, acting styles are mismatched (old-school shtick collides with academy-trained technique), and the films seem to encompass multiple worlds at the same time.

If you’re ready for something like nothing you’ve seen before, and are prepared to set aside your preconceptions about what constitutes cinema and view the world through a different lens, then get onboard. Here’s the African experience in all its violent contradictions: corrupt cops paying a visit to a witch doctor in a BMW, curses that can turn a woman into a vagina dentata, jolly jesters and born-again Christians, occasionally all-singing, all-dancing. It’s sheer invention, born of utter poverty, from people desperate to tell themselves stories, to forge a cinema culture of their own, like the one they know from TV or video—but rooted in their own experience.