Of Love and the City

The word is that In the Mood for Love, Wong Kar-wai’s latest urban fantasia about two neighbors whose spouses are having an affair, is a departure for the director. For aficionados, it's a welcome return to the contemplative tone of his earlier mood-drenched period piece, Days of Being Wild. True enough. In the Mood for Love is composed with a more sedate camera than the tactile handheld pov of the previous movies, and it shares with Days of Being Wild a Viscontian immersion in the ambience and mores of Hong Kong in the early Sixties. But in all other ways, the new movie is entirely consistent with the director's development since Chungking Express.

The last few films in particular feel like reconnaissance flights over dangerous interpersonal territory, getting off vivid snapshots of emotional stalemates in play. Wong Kar-wai has perfected a giddy technique, which appears simultaneously to delve into and flit past the repetitive avoidance strategies and game playing of lonely individuals or couples (at times, he seems like a healthier, more sensual Egoyan). Not uncommonly for a modern filmmaker, he has less of an aptitude for emotional gradation and development than for rough and ready, lunging portraits of emotion-as-action. His films are made up of moments that seem to have been grabbed out of time, as though he’s almost always just missed it.

What makes the movies feel like special events, and what makes Wong Kar-wai feel like the Jimi Hendrix of cinema, is the way every emotional tone is blended into the swirling color and motion of city life. As a city filmmaker, he’s without peer. He understands the city as more than just evidence of Western infiltration (Edward Yang), as a physical entity that exerts its influence over human affairs (Tsai Ming-liang), or as a romantic repository of dreams (Woody Allen). He sees it—guiltlessly—as the natural state of contemporary men and women, operating at the correct speed, the sedate rhythms of rural life being a thing of the past. And just like Hendrix with his endless bag of tricks, effects segue into one another with matchless fluidity, and the viewer/listener gets a quick trip to heaven. During moments like Tony Leung’s fast-motion elevated train ride through the glittering Taipei night at the end of Happy Together, questions of representation drop away and film viewing gives way to pure ecstasy. Like Tarantino and Wenders, those other art hero epiphany-builders, Wong Kar-wai is continually going skyward, exploding his exclusive, up-to-date form of cinematic beauty over the narrative like a fireworks display. What makes him a genuinely great director is the fact that his fusion of speed, color, and vision, always linked to desire, dictates both the form and the subject matter of his work.

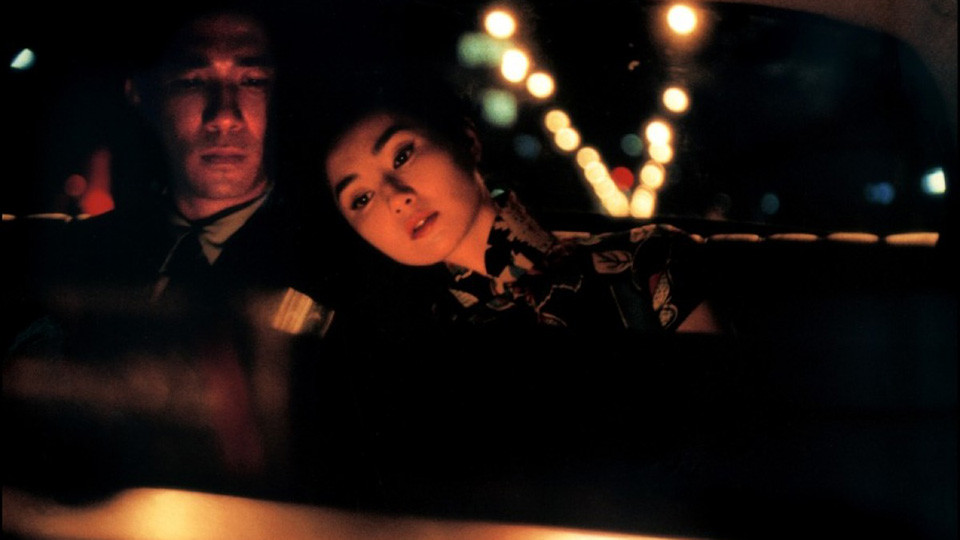

The fluidity is still there in the supposedly “classical” In the Mood for Love, as is the merging of emotional and physical (meaning urban) space. This time, the director’s eye gets quick fixes on states of decorum, good manners, politeness, swallowed feelings, which register fleetingly but vividly. There’s a piercing moment early on (one among many) where Maggie Cheung’s Mrs. Su is sitting in her neighbors’ crowded room, a beehive of activity, nonchalantly reading the paper. There’s a faint smile on her face to signal the appearance of calm. Her carriage is erect, her back arched and barely touching the back of the chair. Meanwhile, she’s wearing a dress in which it’s virtually impossible to be comfortable.

In the world of 1962 Hong Kong, which is so overcrowded that people rent out rooms in their apartments to middle-class couples, where the old folks watch the younger ones like hawks with culturally ordained authority, appearances are all-important. The film gets directly at the feeling of always putting up a good front, of being on guard against disappointing people, by isolating small physical events in corridors, tiny rooms, restaurants, offices, street corners. This time, the viewer isn’t carried along by the gorgeous restlessness of the camera (best exemplified by 1996’s Fallen Angels) or the Polaroid-ish visual scheme that reached its peak with Happy Together.

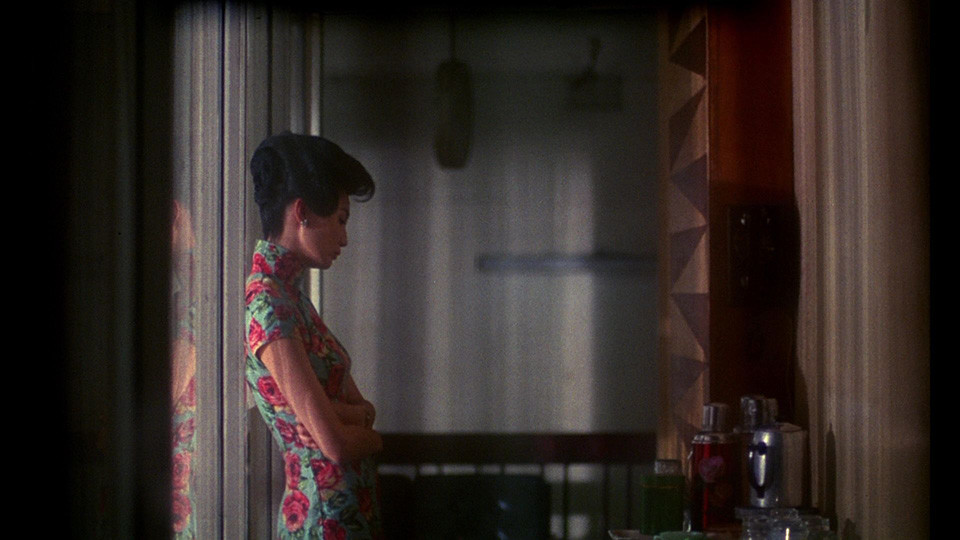

In that film, Chris Doyle’s cinematography suggested a happier, more modishly color-saturated Robert Frank job (Doyle is one of two cinematographers listed on the credits of In the Mood for Love, and it’s debatable how much of his work survived the final cut). But Wong Kar-wai’s visual music hasn’t disappeared—it’s just spikier this time, more rhythmic than melodic. In the Mood for Love moves with elliptical stealth. Very often, the only indication that time has passed is the color of Maggie Cheung’s outfit: she wears the same style of Mandarin, or cheongsam, dress throughout the movie, and unless you’re paying very close attention, you may not notice that a change from blue to red or green has signaled the passage of days, weeks, sometimes months.

The strategy gives every moment real emotional urgency. In the matter of Cheung’s Mrs. Su and Tony Leung’s Mr. Chow, you start to ask: How much has changed with the passing of time and how much has stayed the same? How many times will these kind, proper, self-deprecating people displace their longing—for their spouses, for each other, for emotional freedom—with another ritualized walk to the local noodle-shop followed by another night alone? Every Wong Kar-wai movie has its own brand of sumptuousness. This one is more restricted than ever before in its locations (it’s almost all interiors) and visual focus. In the previous films, part of the thrill was wondering where the camera was going to alight next, and the knowledge that a scene was more likely than not to end up in a spatial configuration radically different from the one in which it began. A good portion of Happy Together takes place indoors, too, but Doyle’s camera finds so many small wonders that it feels as vast as a rain forest. In In the Mood for Love, the camera is pinned down, obliged to repeat the same povs again and again on repeated activities and behaviors, like musical refrains—Leung and Cheung knocking on each other’s doors and talking to each other’s offscreen spouses, Leung’s wife barely glimpsed behind the partition at the hotel where she works, Cheung walking down the steps of the noodle-shop and wiping the sweat from her brow with the back of her hand.

But even within the film’s locked-down symmetries (which replace Wong Kar-wai’s usual lachrymose voiceover as a structuring device), every shot remains a quietly ravishing event. Cheung passing her hand over her husband’s back as he plays mahjong, then sitting on the edge of his chair, in slow motion: a sad, graceful moment, where the line of her body conveys the sense of a woman playing the dutiful, admiring wife. The palette may be more restrained than in the previous movies (heavy on grays, whites and beiges, with great swathes of red), but every object glows as ecstatically as ever. Dramatically, In the Mood for Love isn’t terribly different from Happy Together, which had a similarly fraught, episodic, improvisational shoot. Once again, the structure is theme and variations; once again, the focus is the predicament of a couple.

The earlier film was about two wayward souls wedged between staying together and parting. The new film is about two people who’ve built their identities on foundations of niceness, who suddenly find themselves stranded and clinging to each other, but who are finally too self-censoring to give in to romance. Whereas most of Happy Together consists of Liu-fai and Ho-ping’s dance of devotion and rejection, most of In the Mood for Love is given over to Mr. Chow and Mrs. Su’s dance of longing and fear, interestingly refracted through an odd dramatic device: each one playacts the role of the other’s spouse, in order to understand the affair, or possibly (intentionally? unwittingly?) re-create its dynamics. Every other character—Li-zhen’s philandering boss, Chow’s happy-go-lucky friend, the nosy landlady (“Young wives shouldn’t stay out so late—people will start to wonder”)—is a satellite, and the husband and wife go almost unseen, their offscreen voices used as rhythmic punctuations in a movie that feels less like a narrative than a beautifully drawn-out musical improvisation—Wong Kar-wai’s “Blue in Green.”

Both films lean more heavily on one character than the other. Happy Together was Leung’s picture, but In the Mood for Love belongs to Cheung, whose beauty lights up the movie like the polar star lights up a winter sky. Cheung is one of the few modern actresses who understands her own physical beauty as an expressive instrument, and who also has the smarts and intuition to take it somewhere substantial. There have been plenty of portraits of repression in the movies, but they’ve rarely been as filled-out or as radiant as this one.

Acting for Wong Kar-wai is a totalizing experience—since there’s no script, the actors and the director are creating characters, a dramatic arc, and a new expressive vocabulary all at the same time. Cheung and Wong have found as graceful and supple a throughline for her Su Li-zhen as it’s possible to imagine. Even more than for Leung’s Chow, with his gelled hair and immaculate bourgeois wardrobe, the clothes make Li-zhen: they dictate the way she moves, and the rigid tension with which she displaces her anger and her desire. Cheung understands that the machinery of repression can’t reveal itself too readily, but can only be divined through her character’s strenuous efforts to keep it up and running (in comparison, Leung plays the Mr. Nice Guy act a little too broadly at times). She understands the inherent sadness of being a “good person.” There’s a moment late in the film where she’s framed in a window, as carefully as Dietrich was framed in the shadows for her final Shanghai Express prayer. It’s a portrait of beauty at the service of a thankless goal: to draw a veil over a heart that’s sacrificed itself to the happiness of others. Cheung’s is a genuinely heroic piece of acting, and it puts the vaunted best actress award at Cannes to shame.

Where In the Mood for Love differs from Happy Together is in its decenteredness and lack of resolution. The further the new film moves from the core dilemma in the cramped apartment, the more diffuse it gets. Chow’s move to Singapore feels vague, as does Li-zhen’s phantom visit to his apartment while he’s away at work. This is the film’s ultimate almost, the capper to a series of near-intimate moments where inner propriety dampens passion. Which would be perfect were this just another movie about two people who don’t sleep together. But there are quite a few layers of complexity generated between these characters. Are they actually in love with one another? Or are they in love with the idealized images of their spouses they project onto one another? Or are they just friends who share a need for love and companionship in the abstract? The film touches on all these possibilities, and when it’s at its most powerful it suggests that they all exist side by side. This delicate, not-so-brief encounter, probably long forgotten by both Chow and Li-zhen (there’s a strong sense that all the action is being remembered—it has something to do with the film’s breathless movement forward), deserves to be sifted from the ashes of time, in the same way that the story itself was sifted from the myriad possibilities Wong threw down during the epic shoot. It’s all there, but a little fancy intellectual footwork is required to tie everything together. Near the end, when we’ve skipped ahead to the troubled, destabilizing year of 1967, Li-zhen goes back to her old apartment house with a child in tow.

A few months later, Chow comes to visit their former landlady, who’s left for America. He’s told that her old apartment is now occupied by a woman and her son. He thinks nothing of it and leaves. The near-miss is a timeworn, instant heartbreaker, but it feels odd here—if they were to meet again, what would they say to each other? Would they sleep together? Or would they just keep on being polite? As for the coda, where Chow whispers his secrets into the wall of an abandoned temple at Angkor Wat, it doesn’t really carry much weight (hilariously, there’s a “Tell your secret!” section on the official In the Mood for Love website).

For some people, the spatial, geographical, and rhythmic change-up is perfect. To these eyes, it feels like a failed version of Happy Together‘s final side trip through Taipei, as off the mark as its model was on the money. In a sense, In the Mood for Love tries to duplicate Happy Together‘s similarly improvised final form: one couple’s dynamics are replaced with another’s; Hong Kong on the eve of June 1997 becomes Hong Kong on the eve of the Cultural Revolution and the escalation in Vietnam; the Taipei subway becomes a Cambodian temple; and the falls at Iguazu find their equivalent in the secret desires locked in Li-zhen’s heart, betrayed by her too-eloquent body language and mournful gaze. But where the geographical displacement of Happy Together gave resonance to the whole idea of going home, the idea of leaving doesn’t do much for In the Mood for Love, which probably would have found a more fitting resolution with a staccato move, a sudden rupture. On the other hand, why complain? This is as intoxicating, as exquisitely nuanced, and as luxuriously sad as movies get.

It’s been a while now since Wong Kar-wai first cast his spell of melancholy urban enchantment over America’s more adventurous moviegoers. When he first broke with Chungking Express in the mid-Nineties, it was like tuning into a fresh signal on a new frequency: his filmmaking felt as though it was driven by a seductive urge to dissolve the viewpoints of director, camera, lonely-hearted hero, audience, and screen into one throbbing, super-sensitive entity. Wong made quite a team with his DP Chris Doyle (actually, there’s a third, less flamboyant silent partner: production designer/editor William Chang). Young directors from all over the world wanted to work with Doyle—plenty of older ones, too. His cinematography had a personality, even a mind of its own. The more love-struck neophytes wanted to be Wong Kar-wai, the handsome guy in the colorful sports shirts, forever smiling from behind his dark glasses, who made movies on the fly starting with nothing more than an inspiration, like a painter or a sculptor or a choreographer.

Now, in the year 2000, his newness is a thing of the past, the imitators who tried to perfect the slurred-motion effect of Chungking Express have come and gone, and he hasn’t made the kind of impact we all hoped he would in the American market: this was one secret cinephiles never wanted to keep to themselves. For those who love his films, it’s hard to separate them from the legends behind them: the insane financing schemes, the endless shoots, the patient, devoted casts and crews, the hours and hours of material shot and discarded, the marathon editing sessions in an effort to beat the Cannes deadline. It’s difficult not to see each movie as the final result of a long, heroic undertaking. And the stories and myths endow them with a certain interactive splendor. Somewhere, there’s an alternate universe where the character played by Stanley Kwan in Happy Together is alive and well, and Maggie Cheung and Tony Leung make love with abandon. I’m sure these moments and characters are just as fully achieved as their corollaries in the finished films. This is an artist who’s generous to a fault, compiling a stock of grace notes and delivering the finished films, and the sagas of their creation, like gifts to his audience.

Contributing editor Kent Jones thanks Vivian Huang for her help.