O LUCKY MAN!

Fifteen (or so) uneasy pieces:—The school for salesmen.—Not the deserted village but the redundant factory.—Strange denizens of a middle-class home away from home.—Explosive events among our not-so-civil service.—Medicine à la Mammon, or Human Factory Farming.—Harvest Home, or an English Il Miracolo.—How high the finance.—Flags pass, but trade remains.—Black Power considered as double-entry bookkeeping.—Another visit from the police.—From gold bars to prison bars.—Stone walls do not a prison make, if the spirit soars on wings of high ideals.—The Birdman of Wormwood Scrubs.—With the Sliver Lady Among the Savage Dossers.—Disheartening ingratitude of the lumpen.—Film director as “enlightened” Head Master.

It’s either If… or oh unlucky Jim.

Say cheese or the Clockwork Man.

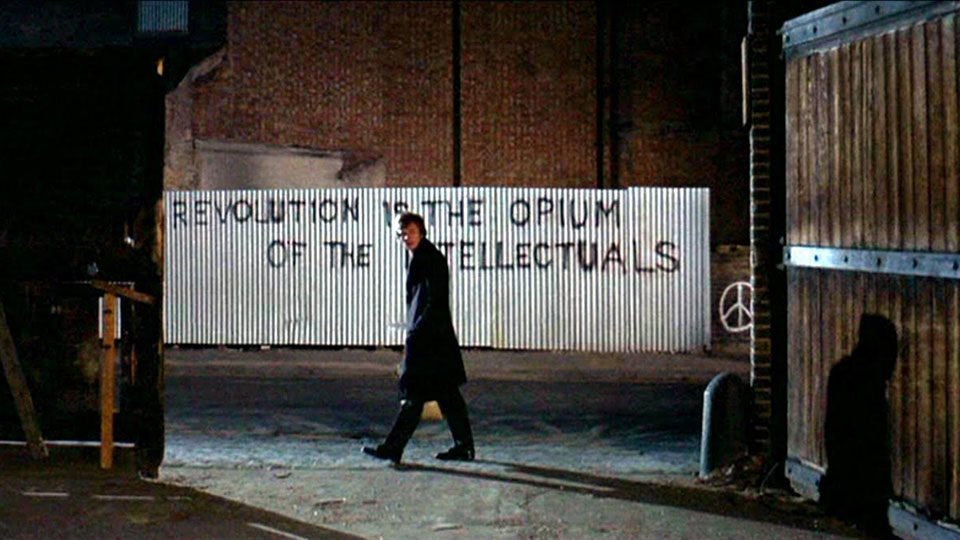

Next time you say Revolution, Smile.

North by Northeast, or Opportunity Knocks, or This Is Your Life That Was. The loneliness of the long-distance commercial traveler. Did you hear the one about the death of a salesman?

Food, inglorious food.—For the boys in blue, a bag of cheese. For the Third World, a taste of honey. For daddy’s little groupie, a breakfast pastorale, or Room at the Rooftops.—Will the young gentleman be having tea?, or Tea and Aversion Therapy.—Two types of cannibalism: (1) milk from the breasts of Mother Church (with a country mother’s Madonna Complex); (2) Medical science turns prodigal son into fatted sow.—Consumer society, or You Are What We Eat.—Charity soup is better than hot water.

In a hungry world, the disintegration of commensalism.— Films about meals: Tom Jones, Fellini Satyricon, Topaz and Frenzy, Tristana, 0 Lucky Man, Deep Throat.—”He’s a sexual mechanic, only with him it’s food.” (John Osborne, Look Back in Anger.)

The Miracles of St. Midas, or transubstantiation as a social system. All that’s yellow (cheese, loaves, honey) turns to gold (fire from heaven for the wretched of the earth). The war drums of honey guard our golden age. Meanwhile, back at the building site, down among the methsmen: hot soup, bonfires, oil drums like steamrollers. On the wretched continent, it’s black eat black. In the interstices of the Welfare State (that Sea of Holes), the Socio-Salvationist cry of “Brothers!” sparks the flashback of rage; for, where working to be exploited is the condition of self-respect, truth is a two-edged sword.

Rural Rides, or Lindsay in Lestershire.—Only the fancy-dress Maharajahs of Help! disguise themselves as the mandarins of high finance.—Even in England’s green and pleasant land, there’s always a Mafia. —In the Boultings’ Fifties, it was Commie shop-stewards (Peter Sellers, Bernard Lee). In the Harold Wilson Sixties, it was the gnomes of Zurich. (90% of whom were Home Counties stockbroker belt But Land-of-Milk-and-Waler Harold didn’t like to say so for fear of inspiring a further stampede from the pound and giving another screw to the class war, whereas Wilson sought a technological détente.—From our Economic Correspondent.) In the Common Market Seventies the bowler-hatted gentlemen whose word is their (James) Bond hire Transport Command on the Old Boy Net. Oh, oh. O what a nasty peace.

From Industrial Britain (Flaherty) to Distributive Britain (Anderson). From a hymn to tea in Song of Ceylon to a ballad of barter: honey for coffee, or (by free association) Song of Biafra.—”The World in Your Coffee Cup,” or John Grierson’s nightmare. From Kipling’s If to Anderson’s If…

Unlucky for some. Once upon a time, they chopped your hand off for thieving. Lucky for us. The hands of unconscripted youth roam freely over the electronic keys. From silence to sound from “quick cutting” to foreground music, from small screen to Scope-0-Rama. But free speech leaves us each as a square peg lost in the endless succession of sprocket-holes we call the System of Empty Stomachs. A crucialfixion on the Maltese Cross.

As This Sporting Life is to Room at the Top, and If… to Billy Liar (a public-schoolboy’s thought-balloon), so 0 Lucky Man is to Nothing But the Best. And it is to This Sporting Life (“there’s no way of making it”) as Charlie Bubbles is to Morgan (“there’s no way of saying it”).—After the foggy-gray anger of Kitchen-Sink Britain, after the kaleidoscopic pixilation of Swinging London (where LSD briefly did not mean LSD), comes the ironic gloss of post-Beatle Britain, with George Harrison gone East and Mike Jagger Latin American, leaving Late Mods on a stagnant island, like wolves on a melting ice-pack.

Son of the Beatles vs. the Red, White, Blue-Gray, Pinstriped, Bowler-Hatted, Wax-Mustached, White-Coated and Plain-Clothed Meanies, Recantations: What a Friend We Have in Jesus; When This Blood War Is Over; Everyone Is Going Through Changes,/No One Knows What’s Going On.—Shock of Ages, Future Rock.

From “Together!” to “Brothers’”—The winos may only be lumpen, but are they also the working classes in tactfully extreme metaphor? (But the two young aristoes stick together; they can afford to.)

Alan Price, as a young man: “If you have a friend on whom you think you can rely,/You are a lucky Man!” Aristotle, as an old man: “Oh, my friends, there is no friend!” The pop singer learned it early in the game: the precocious, smiling wisdom of capitalism, which is the war of All against All.—The Instantcoffee Opera.

The traveling life: post-Marx, post-Pudovkin, post-Brecht, post-Godard. Instead of One Plus One: One Is One And All Alone And Ever More Shall Be So. The Alan Price Set, or British Sounds.

Chameleon character actors, or Everybody’s Anybody, or Background Maketh Man, or Putting the Layers on Peer Gynt’s Onion. (But where the devil was Joe Melia?) Here Comes Everybody, or The Many Faces of the Faceless English: Alec Guinness, Peter Sellers, Benny Hill, Dick Emery.

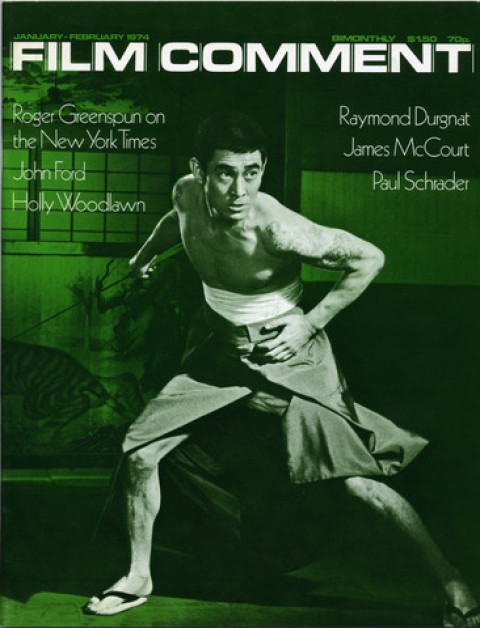

Moira Shearer got her red shoes from the diabolic cobbler This pilgrim gets a glitter suit of gold and green (for envy, fertility, faerie) made, by magic measurement, by Ralph Richardson I, perhaps a retired East End garment manufacturer, like David Kossoff in A Kid for Two Farthings (take that, Wolf Mankowitz) or maybe even Vittoria De Sica in The Millionairess.

This green young “knight errant” enjoys one sweet taste of success, and sups at the High Table of International Diplomacy, like Bernie Cornfeld or Bloom, the self-made magnates who loom among the culture-idols of young England’s moddom. The film says it twice: Beware of (Sir) Ralph Richardsons bearing gifts, of giving their word; because as Wolf Mankowitz said it in the song Val Guest discreetly dropped from the movie version of Expresso Bongo: “Nothing is for nothing,/Nothing is for free . . .” The rising poor, edged gently on by Ralph Richardson I, provide scapegoats for the established rich (Ralph Richardson II).

Alan Price, or the commentator who knows the score (or, should I say, keeps good account). He plays the game, he sings the truth (but not too openly), he shares the rich man’s daughter with his mates, he drives through the night and he’s going from gig to gig, not picaro but pilgrim. A minitribe of temporary brothers, with friendly knocking-van.

Alan Price, mingling epoques. Sitting at the electric organ, he evokes the swinging Sixties. But with his long, lean, lantern-jawed, very English face, he still seems more Forties Tommy than pop-idol puff-up. His smile and lyrics distill a Brechtian wisdom whose irony has been naturalized (at last) via the proletarian irony lurking in softrock-hardpop. The sons of the dockers in Every Day But Jesus’s Birthday have learned a thing or two.

British justice at play, or the delicious twinges of immunity…

Malcolm McDowell, or the post-Finney face. After Angry Young England, Swinging London, Paranoid London (Michael Came as Cockney double-agent, seedy but on an expense account), now Sagging England, as the spotlight shifts to a newer generation: young, innocent, unidealistic mods setting brightly out to make it—as if Heathco’s England were still Harold Lloyd’s America. Samuel’s Last Smiles.

Seaton, Machin, Alfie, Billy, Bubbles, Morgan— the bastards always grind you down, or lock you up, or set you drifting in the clouds. Compare and contrast: The Stooge, The Patsy, The Ladies Man, Centre Point or Bust.

M. McDowell: “What is there to smile about?” R. Tushingham (in A Taste of Honey): “Oo’s appy?”

Question 22: List at least three hundred references to other films. Consider any ten in relation to the similarities and distinctions between plagiarism hommage, collage, parody as irony, internal transformation by external context, Surrealism by sense of déjà-vu, bisociation (Arthur Koestler in The Act of Creation), the Zeitgeist and its repertoire of icons, the relationship of motif to cycle and genre theories, Georg Grosz and expressionism.

Question 23: Storyboard the same master-scene script as rewritten by Preston Sturges.

Instead of plot structure: a sequence of suggestions.

Has color, with its increasingly accurate subtleties, now earned the “presumption of reality” once monopolized by black-and-white? Poor Cow used color for squalor without irony; Up the Junction got color almost right for mind’s-eye nostalgia. But, given the ironies of O Lucky Man, is there a sense in which it transposes a kind of realism into gloss? The visual packaging is irony. The content (of the style, i.e. the surface package) is that of an optimistic dream always turning nasty—half-awakening, the dreamer turns over, and, relentlessly, the unconscious scriptwriter sets up another episode.

If Ralph Richardson and Malcolm McDowell were played by the old and the young Alec Guinness respectively, would the green Lurex suit evoke The Man in the White Suit (Mackendrick-Ealing, before austerity became affluence)?

Is O Lucky Man the best Polish film about the British since Repulsion, Cul De Sac, and Deep End? (Or Making It, English-style.)

An Innocent At Home.—This salesman-pilgrim-picaro’s refress concludes with the salvation of his soul, briefly at least, since he’s learned that life is not a matter of Smilin’ Through, that capitalism’s merry-go-round is just another la ronde: “the vortex of commerce,” as captains of industry said in the Thirties.

They also predicted that artists would be increasingly lured into it, although kicking and screaming. And the Television Mail once carried a full-page, front-cover advertisement to the effect that “Lindsay Anderson and Karel Reisz now make commercials exclusively for Blather & Doubletalk Ltd.”—Standing Up for Jesus Bending Down for Mammon; pulling your cheeks apart (vide A Clockwork Orange) so your kindly warder-paymaster can spot your talents and push his dimes and dividends all the way up your fruit machine. Thus do left-wing Samsons toil at the mills of capitalism. The young lions of Free Cinema and Revolution all get whirled off in a dance of apparent spiritual death, along with John and Roy Boulting, Roy (Ward) Baker, Uncle Joe Losey and all.—But one can shift the pay-packet and the capital of prestige from your right hand to your left, robbing Mammon to pay, if not exactly Marx or Trotsky, then at least some angelic figure of wrathful truth. That the director enters his own film to hit his not-yet-lead over the head with a script, like a testy classics-master with a Latin grammar, is self-criticism, no doubt. But it s also an unsmiling invitation to collusion-for-subversion; it’s the countenance of John Knox or Lenin; it’s the nitty-gritty revealed to a few million people who believe In capitalism’s cash-register smile and the Altar of Ad-mass in every home. The lies of Communist monolithism are only one of a thousand alternatives to the lies of consumerist fulfillment. But a cynicism that accepts self-criticism and incorporates it into the attack is the only one that isn’t sterilized by holier-than-thou hypocrisy. To ask for much more is usually pseudo-idealist mystification—like telling an anti-pollutionist, “Who are you to talk? You exhale, don’t you?” If Lindsay Anderson now accepts the pessimism for which he once flagellated Elia Kazan (re On the Waterfront) before he recognized it himself, the result is artistic growth, into a black tragicomedy like Swift’s—a venerable, versatile, and formidable position. Reinhold Niebuhr compared the innocently reverential “children of tight” with the twice-bitten “children of darkness,” whose implacable cynicism is simply hope keeping a low profile. The courage of cynicism is affirmation, whether unknowingly or despite itself.

Must revolutionary songs, like LPs, go round and round in ever-diminishing circles until the singer exits through the hole in the middle of a top-ten record?

In Every Day Except Christmas, the trucks roared through the night, as BBC broadcast the epilogue. Thus the whole system made sense. But this salesman keeps his car radio on, and DJ banalities becomes irrelevancies, distractions, lies.