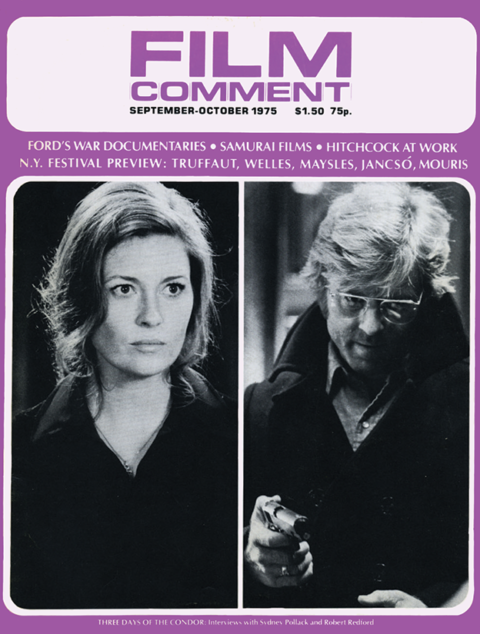

1975 NYFF Preview: Grey Gardens

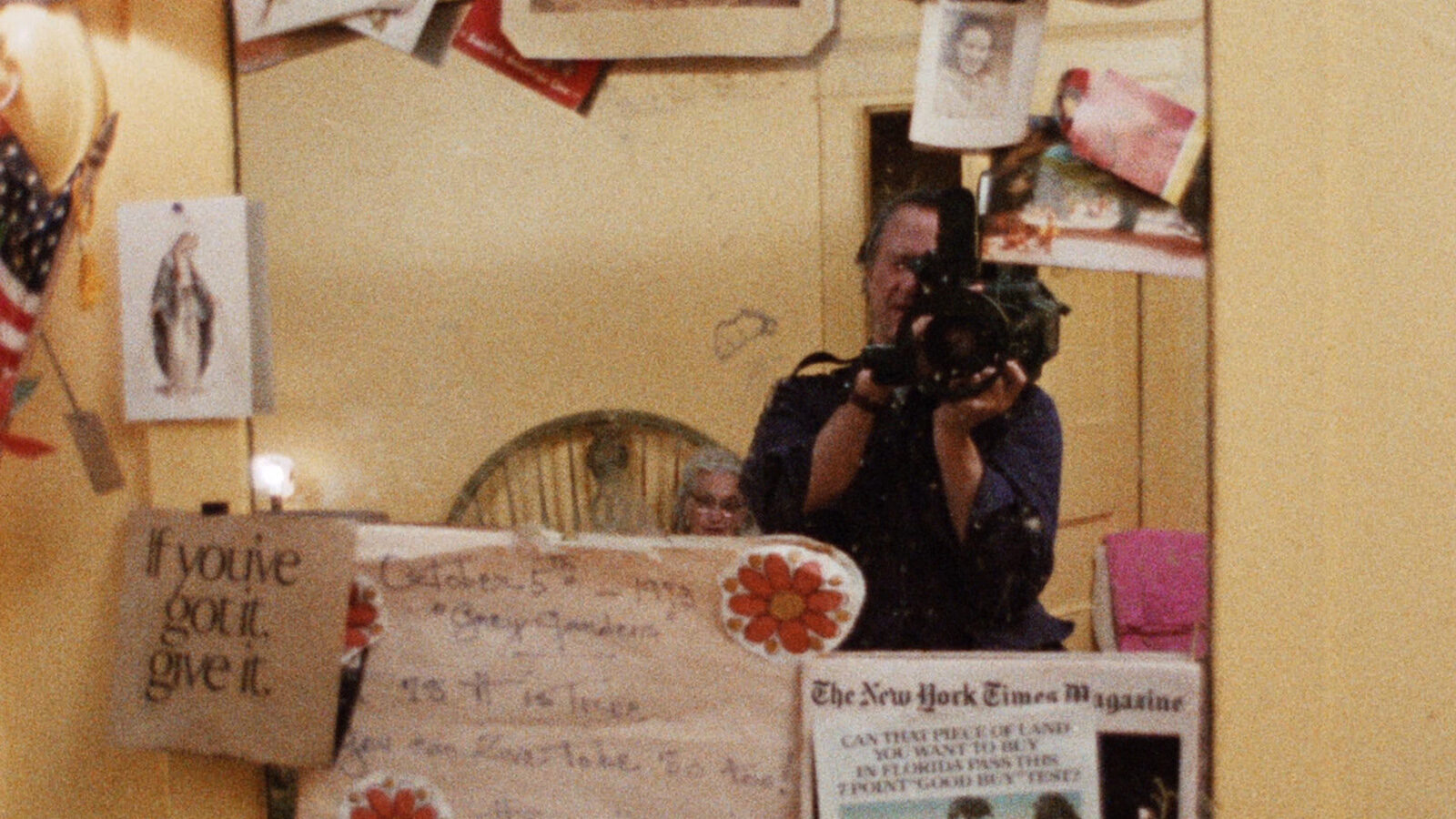

Cinéma vérité, which has fallen into low estate in recent years—thanks to the likes of public television’s An American Family—is triumphantly vindicated by Albert and David Maysles’s Grey Gardens, an extraordinarily crafty invasion into the lives of Edith Beale and her daughter Edie, better known as Jacqueline Onassis’s impoverished aunt and first cousin, whose own fallen estate in East Hampton, Long Island, made gossipy headlines a few years ago. After a Wellesian nod to those headlines and the local scandal that generated them, and after a graceful, passing admission of their own presence as filmmakers, the Maysles brothers prowl the dilapidated Beale manse with an unblinking cool—underscored by an ironic, growing compassion—that achieves what cinéma vérité aims for but seldom conveys: a sense that the material is telling itself.

In the course of the film’s feature-length running time, that material becomes hypnotic—as much so as the story of the stunted lives of Miss Havisham and her ward Estelle in Great Expectations, or of Faulkner’s ghoulish spinster in “A Rose for Emily.” Squatting dimly in the midst of Long Island’s gold coast, a falling-down frame house behind tattered privet hedges and a briar patch of unpruned trees and bushes, Grey Gardens (as the Beales call their hermitage) is a genuine haunted house of the kind that would intimidate even the most intrepid Halloweeners. But inside, the ghosts are very much alive: two shut-in survivors who live on their past dreams, on their contemptuous fear of the outside world, on their comfort in incredible squalor, and, most of ail, on each other’s nerves.

A deeply weathered semi-invalid in her late seventies who goes about dressed in little but a beach towel, Mrs. Beale has, more or less gleefully, distilled her life to three obsessions: memories of her unrealized career as a concert singer, the whereabouts of her dozen or so cats, and the shortcomings of her daughter. In one of the film’s many moments of gently prompted revelation, the Maysles brothers observe the old lady sitting in her bed littered with the debris of years, wearing a huge straw sunhat and singing, in a perfect echo of Gertrude Lawrence, “Tea for Two.” In another, she grandly encourages one of her cats to relieve itself behind a discarded, gilt-framed oil portrait of herself as a glamorous society woman of the Twenties. In one breath, she rhapsodizes about the beauty of her daughter as a young New York debutante; in the next, while Edie preens before the camera, she maliciously makes fun of her daughter’s spreading frame.

With a mother who at best is an amusing tyrant, Edie Beale herself is at best a valiant victim. Her face carefully made up, her head swathed in a succession of tight-fitting scarves and hoods (which leads one to wonder whether she shaves her head), she emerges as a self-made nun in heat. As a debutante in a fascinating series of old family photographs, she was indeed beautiful—a vivacious, leggy girl with Miss America looks. Now, as seen by the Maysles, she is a still-handsome enlargement of herself, a cut-up in thickening middle age. Turned on by the presence of the camera and the unobtrusive but undisguised encouragement of the Maysles, she mugs shamelessly as she rambles on about her former promise as a cabaret performer, the men she almost married, the glamorous life she could have had—but, and here she is touchingly uncertain, for the needs of her mother. A grotesque figure of bathos, she becomes, under the filmmakers’ scrutiny, a creature of pathos. A shot of her in the ocean, swimming with a perfectly schooled crawl stroke, suggests in one beautiful, quiet sequence that not all of the promise of her background and youth has vanished.

Shot over a period of several months and edited in free-flowing scenes to convey the time-suspended, nearly stagnant whirlpool of life inside the haunted house, Grey Gardens raises in high relief the usual, vexing questions of cinéma vérité: how much are the filmmakers manipulating, exploiting their subjects? and how much are the subjects manipulating, exploiting them? In the end, it resolves these questions in one shattering moment. Suddenly, Edie advances toward the camera exclaiming with real passion to the filmmakers: “I love you.” Scornful at first, then finally outraged as she sees her ward attempting to escape, Mrs. Beale rises from her bed and demands over and over again that Edie shut up. As the battle of nerves and wills rages, what has been implicit all along becomes clear: if the Maysles have been exploiting their subjects, the subjects have been exploiting them as well. And it’s a tug-of-war of equals, for in Edith and Edie Beale, the Maysles are luckily contending with subjects that every cinéma vérité film must have to succeed—brilliant, genuine performers.