Notes on Shadows of Our Forgotten Ancestors

Sergei Parajanov’s Shadows of Our Forgotten Ancestors is one of the most unorthodox, colorful, “formalistic,” (in the West read “arty”), religious-superstitious and sensual-erotic films ever made in the Soviet Union. Winner at Mar del Plata and talk of other (non-competitive) festivals, the film has proved a sensation both outside and inside the USSR, considering the admitted mediocrity of Parajanov’s previous pictures. Thus it is all the more interesting to read the director’s own story of how he made Shadows—which has enjoyed very little commercial success in the USSR, partly because it was not given much of an advertising push and has thus quickly dropped out of sight.

But another reason for its disappointing box-office in the Soviet Union is undoubtedly its visual, offbeat, impressionistic structure that lacks a strong story line and “psychological realism,” and that replaces these factors by “non-actors” in flashily-photographed wordless scenes harking back to the great days of Russian formalism in the 1920s and early 1930s (Kuleshov, Vertov, the early Eisenstein and Pudovkin, et al). Then, as now, the Soviet public-and publics abroad too-do not always take too kindly to “intellectual cinema.” But at the same time it must be mentioned that the current Soviet film press did give very kind treatment to Shadows, and the anticipated onslaught from the conservative wing against the film’s obvious “formalism” did not materialize. In fact, some critics have spoken sadly about how Shadows played in only five theaters in Moscow (where saturation booking is standard practice) and was “laughed off the screen by audiences” in a very short time.

Before Shadows, none of the film ‘s cast and crew had had much reputation in the USSR or elsewhere. Parajanov had worked for ten years at the Kiev Studio without any artistic success; the young cameraman, Yuri lIienko, had shot only two films, although one was the very promising comedy Farewell Doves; co-scenarist Ivan Chendei had been, and is, a moderately-published contemporary Ukrainian writer; actor Spartacus BagashviIi (Yura the sorcerer) had previously been known mostly in his native Georgia. Of the three younger performers, Ivan Mikolaichuk (Ivan Paliichuk, the hero), a native-born Carpathian, was a theater student without film experience; Larisa Kadochnikova (Marichka Guteniuk, the hero’s first, spiritual love) had been an unsuccessful candidate for the role of Natasha in War and Peace; and Tatiana Bestayeva (Palagna, the hero’s second, earthy love) had been virtually unnoticed. These three young performers, as a result of Shadows, have been getting plenty of work. And, of course, all the Gutsul natives of the Carpathian region depicted in Michael Kotsiubinsky’s pre-Revolutionary novelette (on which Parajanov based his film, on the centennial of Kotsiubinsky’s birth), were recruited on the spot and are 100% “non-actors,” or as Eisenstein would have called them, “models” (cf, also Eisenstein’s “typage”).

Sergei Parajanov himself (full name Serghei Iosifovich P.) was born in 1924 in Tblisi, Soviet Georgia, of Armenian ancestry. From 1942 to 1945 he studied in the Voice Department of the Kiev Conservatory of Music. In 1951 he graduated from the Directing Department of the Moscow Film Institute, where his fellow students included Marlen Hutsiyev, Alov and Naumov, and Nicholas Figurovsky. His teacher-or workshop leader-was the Ukrainian director Igor Savchenko (1906-50), and he was also tutored considerably by Leo Kuleshov. Parajanov’s B.A. film project was the short Moldavian Fairytale (Moldavskaia Skazka, 1951). He also served as apprentice of assistant director on The Third Blow (Tretii Udar, 1947), Taras Shevchenko (1951) and Maximka (1953).

Parajanov then got a job directing features at the Kiev Dovzhenko Studio, where he has worked since, making Ukrainian-language “national” pictures for local consumption, without winning any critical notice whatsoever until Shadows. His features are: Andriesh (1954, co-director Y. Bazelian), The First Lad (Pervyi Paren, 1958), Ukrainian Rhapsody (Ukrainskaia Rapsodiia, 1961), Flower on the Stone (Tsvetok Na Kamne, 1963), The Ballad (Dumka, 1964), and Shadows of Our Forgotten Ancestors (Teni Zabytykh Predkov, 1965). In the last year or two Parajanov has been announced to direct two new films; Kiev Frescoes (Kievskie Freski, at the Kiev Studio again); and a tragic biography of the 18th-Century Caucasian poet and monk, Sayat-Nova, starring Sofiko Chiaureli; this is a co-production of the Armenian, Georgian and Azerbaijan studios. One of Parajanov’s hopes is to film the greatest ancient Russian folk epic, “Tale of The Host of Prince Igor.”

Introduction and translation by Steven P. Hill

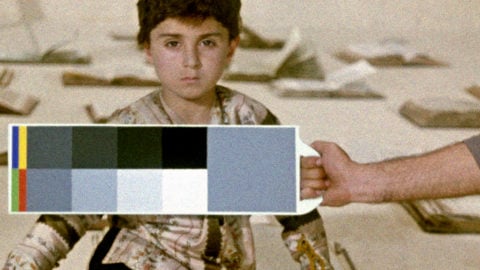

Shadows of Forgotten Ancestors (Sergei Parajanov, 1965)

PERPETUAL MOTION

Many know about this. That there are moments in life when all the habitual ideas, rules and relationships are involuntarily re-evaluated. Moments of highest tension and the greatest attention to life. It is as if you throw yourself wide open, and each new thought, each image that penetrates you, draws after it dozens and hundreds of others, similar and dissimilar. As if the current catches you and only strong muscles are able to withstand the force. These are the moments of maximum self-surrender, of a maximally full and passionate life.

From time to time I can hear the words of my mentor, Igor Savchenko [at the Moscow Film Institute]—“People who think by associations quickly wear themselves out…” Like all my age-mates, I could only vaguely guess then what it meant to think by associations. We saw what a grandiose and indefatigable self-surrender our teacher lived by, and we thought those words referred first of all to Savchenko himself. And this really did refer to him. Only later did we understand that Savchenko had been talking about precisely such moments—the most difficult and the most unforgettable. Often, more often than many others, he experienced this, and from our very first meetings we spontaneously fell under the charm of his thinking, his feelings…

A year after our enrollment Savchenko went to work on the film Third Blow. A freight train was carrying me to the Crimea—me, the assistant director, together with Krupp pillbox and bunker [guns], hinged and soft dummies of Germans, cardboard tanks and flamethrowers. In that summer of 1947, hollyhocks were not blooming on the Kirkinez Isthmus… country women were not painting their huts from German helmets… war, even a movie-war, frightened them. In the hope of getting a grade of “A,” in the hope of getting to know the location, I was dropped with a herd of cows at a mine field of the “Turk’s Knoll.” Here it is, the Genuez Fort, the Kirkinez Gulf… There is even a rabbit running across it from the foxhole—the reliable shelter of the Germans. I recognize the location and enter into it…. In the darkness I can discern a niche for a helmet-Gothic… a niche for a gun-Gothic… bunks in a Gothic arch… a niche for a kettle-Gothic. Gothic, some early, some late, but Gothic. And here is the author who gave rise to the Gothic of the Cologne Cathedral and the Gothic of the Fox Hole. His helmet… he himself… his purse… a decayed army coat. I leave him in the Gothic darkness and come out into the light with my souvenirs. Coins from all the countries that the Germans had crossed… silver, copper, aluminum, Soviet ten-kopecks… and a lock of red hair in celluloid… maybe a child’s?

The helmet. I gaze into it for a long time… From the bottom of the rusty helmet a Madonna looks at me—she is Gothic, too… I involuntarily compare her with the lock of hair… She is red-haired, too.

***

At times it seems to me that I could have filmed Shadows of Our Forgotten Ancestors much earlier, without experiencing so many—albeit justified—failures. It is a bitter thought that only now have I made the discoveries that even my B.A. practice had pushed me toward.

This short little picture, Moldavian Fairytale, is the only one of my past works whose imperfection I am not ashamed of. I remember the first thing that favorably disposed me toward this thing was sketches-the B.A. sketches of one of the graduates of the Film Institute at that time. I had always been partial to painting and had long since become accustomed to perceiving the frame as an independent painting canvas. I know that my directing tends to dissolve itself in painting, and that is most likely its first weakness and its first strength. In my practice most often I arrive at a treatment that is from painting rather than from literature. And I am closest to that literature that, in essence, is itself transformed painting.

That is the way I saw Kotsiubinsky’s novelette [from which Shadows of Our Forgotten Ancestors derived]. That is the way I saw at one time Emilian Bukov’s fascinating novelette, from whose themes I made Moldavian Fairytale. The poetry of this thing came to me almost at once. The songs of a shepherd who had lost his herd—a symbol of love and success—I had heard both in Georgia and Armenia, and then later in the Carpathians, too. I was trying to create an expressive structure working directly from folk poetry and mythology. At the defense of my B.A., [critic] Rostislav Yurenev reproached me for imitating Dovzhenko and his Zvenigora. Right there Dovzhenko stood up for me, guessing quite correctly that I “hadna’ even seen his pictuah.” I watched it later and saw that in some things I was really repeating Dovzhenko. But this similarity didn’t distress me, as we aren’t distressed by repetition of folklore themes. Evidently I had had the good fortune to come into contact with the same spring from which the great poet had dipped.

And then, at Dovzhenko’s advice, I went to the Kiev Studio, to make a new film on the same material. This was Andriesh, a seven-reel children ‘s picture that vividly expressed an absence of experience, craftsmanship and good taste. And that, unfortunately, was only the beginning.

Shadows of Forgotten Ancestors (Sergei Parajanov, 1965)

I have no desire to go into self-torture, but I will say that many of my films are really hard to see again. All the more that each of them is the result of the best of intentions. That cinema that I was striving for required too high a culture, taste and forbearance. Its world ought to have been entered free from the notorious canons, the old habits and impressions.

Directing is a deceptive profession. It is not so independent as sometimes might seem to be the case, for often you have to embody on the screen someone else ‘s theme, someone else’s thoughts, someone else’s images. And if you possess good culture and know-how, you can do quite good things. In those years I didn’t have such know-how—only fine flashes. And that’s no irony: those really were good flashes that I don’t reject even today. Sometimes, very rarely, they happened to slip through onto the screen, in spite of everything, but that had no sense, nor was it organic.

When I began work on the film The First Lad, for the first time I discovered for myself the Ukrainian village-discovered its texture of overwhelming beauty, its poetry. And this enchantment of mine I tried to express on the screen. But under the blows of the plot—and this, in essence, was an unimportant humoresque—the whole building went to pieces. Landscapes, stone women, storks, tractors, straw crowns proved to be out of place.

The material on which the films Flower on the Stone and The Ballad were made is profoundly memorable for me. Folk carving, sewing, metalwork. Ancient songs of the Ukraine. I wanted to convey the world of these songs in all its primeval fascination. I wanted to convey the folk “outlook” without a museum’s coating of makeup—to bring all those overwhelming embroideries, bas reliefs, and patterns back to their creative source, to fuse them into a single spiritual act.

I wasn’t able to do that, for I was trying, in essence, to discover a dead world, one not animated by the presence of man. But meanwhile it’s precisely folklore that suggests dozens and hundreds of excellent treatments. It’s a bitter thought that to this day I have bypassed such a colorful figure of the Ukrainian folk-epic as the “free Cossack Mamai.” It is a most unembraceable image. Like the great Eulenspiegel, he was an artist and singer, bandura [guitar] player and soldier, wander er and freethinker. He is the spirit of the Ukraine, its sorrow and poverty, wealth and hopes. He could tell more than a little about the time, about beautiful and eternal passions—if a real artist would start talking with him.

***

Sometimes we count too much on the strength of experience and forget that some places need to be entered when we are young and have given up our habitual world. So as not to remove the object by our presence.

Most do so sooner or later, and I too have long been absorbed with folk ceramics. I am attracted by Oposhnia and the celebrated Oposhnia clay. From ten thousand pieces I pick out masterpieces of the folk masters Poshivailo and Kiriachok are especially captivating… These are genre scenes, folk tales, fairy tableaus. In the evening I am drawn to landscape… I look over an Oposhnia church on a knoll. Wooden five-cupola construction of late classicism, dating from the last Romanovs. In World War II an artillery shell knocked off a side cupola, by which it disturbed the symmetry and gave the church a certain uneasiness.

The church is still functioning… In saying goodbye, the priest crossed me with his left hand. His right had been amputated in a field hospital in 1943 at Stalingrad.

***

Long before the shooting of Shadows of Our Forgotten Ancestors began, I made attempts to get into contact with their world. At one time I had directed Ukrainian Rhapsody—a picture where my desires and my habits clashed sharply. Their coexistence inside of one picture proved to be extremely ridiculous. The writing of the thing, completely traditional, was rather remote from me. But I lacked the courage and craftsmanship to make use of the theme offered by the writer and create a poetic-philosophical thing. I was asked to tell about a woman who had experienced a traditionally difficult fate and who at the curtain became a celebrated singer. I could see in her biography a fate of passions, caught up in the tornado of war. There is a proverb—”When the cannons speak, the muses are silent.” That is not true. The muses are not silent they summon us to retribution, they sing of victory.

Here what was needed was silhouette, high-contrast lighting, but not illusory chiaroscuro. Light that would be personifying and not at all ordinary [bytovoi]. I could never come up with ordinariness [bytovizm]. And a military helmet acquired a meaning for me when I saw it being used to paint a hut or water calves from, to cultivate flowers in or for a child’s potty chair.

Shadows of Forgotten Ancestors (Sergei Parajanov, 1965)

In my “movie-hospital” a man was lying. He had been brought in after shell shock, burned allover and in a coma. The whole ward looked after him, the junior nurses never left him, the blind sat up nights by his bed. And when he came to, he started speaking German. He called his mother, but did so in German. This moment was thought up first of all as a poetic (non-ordinary) category. It was later thrown out of the film, because it was openly not tied in with those canons that I just had not succeeded in renouncing here. It proved to be from another world.

A matter, most likely, not only of personal inertia. My failures were the studio ‘s failures, too. When I happen to re-see the previous films, I often begin to tremble. I see at times an obvious failure-visual failure, cameraman ‘s failure, actor’s failure, designer’s failure and I am surprised that it did not meet a rebuff. The studio systematically forgave me, and many others too, for these extra expenses… For what? For the “national color” of my pictures, the national texture, the national humor. But to me the sham of all those qualities had been revealed long ago.

The power of a genuine thing, evidently, is that one high note is taken and held to the end. For a long time that note didn’t come to me, although it often seemed that I just needed to try once more and it would happen.

***

We often talked about Pirosmani [unique Georgian artist, died 1918, whose biography is now being filmed by another director], about how he ought to appear on the screen. I could see … a city of black oil-cloth—that very oil-cloth on which Pirosmani had drawn. And in this city rugs weep, hanging down from balconies and galleries. And people in cowboy shirts and pointed toe slippers carry an empty coffin through the side streets. And in front of the procession is Pirosmani. He smiles at the wine cellars and taverns. And in his hands he has—nothing. And at the cemetery a freshly dug hole awaits them… But Pirosmani goes away to where someone noble and rich is being buried, takes his portion of shilaplav and, as he eats the bitter rice, vanishes to everyone ‘s great astonishment…

When I was in Akkerman, I thought it would be good to dismember these walls of white, light-blue, and pink seashell-limestone, in order to recreate in the fresco manner the legend [zhitie] of [Prince] Igor and Yaroslavna. Probably, with a definite color plan and a clever use of lenses it would be possible to recreate the fresco truth—not a pseudo-historic texture, but historical feelings.

Somewhere in my desk there is a drawing. The cemetery of Pine Lachaise… Madonnas of all times and of all kinds—hunchbacked, red haired, starched, dark skinned, indigent, scrawny. And suddenly among them, among these Madonnas, a new symbol of the time, a new cross—forever dismantled and mute, a red propeller.

***

Hardly had I begun carefully reading Kotsiubinsky ‘s novelette on which Shadows was based when I wanted to direct it. I fell in love with this crystally-clear feel for beauty, harmony and infinity. A feel for that line where nature passes into art and art into nature. I already knew some material. Museums, books, drawings. There had been a film, Oleksa Dovbush [1959] about the Gutsul national hero. The creators of it tried to reveal the Carpathians, but once again in the framework of the old writing, the old visual culture.

They dressed Dovbush in red, which designated, as was obvious, the hero’s revolutionary spirit. They came to the Carpathians filmically educated. Most of all they were attracted by the exotic, decorative motif, and we could not recognize the Gutsuls in their film—we didn ‘t see their walk, we didn’t catch the charm of their speech, the course of their thought. When a Gutsul on meeting someone says “hello” instead of “glory to Jesus,” that is an untruth of life and an untruth of art.

I remember how we had once been struck by the beauty of Moldavia—those exotic hills, vineyards, grasses. But Savchenko taught us to absorb ourselves in the material: drink it in like a sponge, so as later to give back and organize that which is the most important part. “The cinema,” he used to say, “ is a man ‘s art. The truth of life is more profound and necessary than your fiction. But, after studying the subject, and coming to know it in all its nuances, you can vary them as you wish.”

Exactly so. I became convinced, when I was working on Shadows, that a perfect knowledge justifies any fiction. I can turn song material into action, and action into song—which I wasn’t able to do when I was shooting Ballad. I could translate ethnographic material, or religious, into the most ordinary and everyday. For ultimately they have one and the same source.

I could be reproached for certain deviations from ethnographic accuracy. The Gutsuls put on masks [melanki] at Easter, not at Christmas. They don’t have a ritual of the “yoke”: I violated accuracy, but it was suggested to me by the Gutsuls themselves. I had heard a song [kolomyika] about a husband harnessing his wife in a yoke—an allegory, designating, if you will, an unequal marriage. And, when my Ivan married Palagna, I performed the “ritual of the yoke” over him. And the Gutsuls who were appearing in my film did it just as seriously and beautifully as all their original rituals.

… After deciding to shoot the film, we left for the Carpathians hurriedly, one after the other. When I arrived on the spot and looked around, I was not exactly gripped by enchantment. Rather the opposite. The first thing that you noticed was connected with the most everyday modern life. I saw European shoes, asphalt, bicycles, high-voltage towers. The cliff where the Guteniuks fought with the Paliichuks is no more—it was blown up when a road was put through. Honestly, I was distressed by this strange combination of the ancient and the young. The buzzing of wires and the drawn-out grief of the horn [trembita]. Gold watches, crowding a sleeve with homespun embroidery… One window of my hotel room overlooked the Cheremosh [River], rapid and meandering, and the other overlooked the asphalt courtyard, across which an old woman once went to the market with her cow, and afterward returned alone, jingling the orphaned bell.

Fate took pity on me. I was moved out of the hotel to a common hut, and from that minute I really began to grasp the shape of that life that I wanted to tell about.

Shadows of Forgotten Ancestors (Sergei Parajanov, 1965)

No literary image is sensual material. You don’t get the humidity of grass, the odor of timber mold. My mouth to this day has the taste of water running from under the roots of a pine. After each gulp there are needles prickling on your lips… The mountains that previously had been seen, so to speak, on the horizon—a beautiful and cold long shot—now appeared in all their primeval intimacy. Travelling around the mountains, every hour we would discover little secrets: why does your leg fall through here or there, where do the springs flow from, why are the roots scorched? White sheep come out of the weeds all red—the undergrowth is full of bilberries. In the forest on the hills I find lost bells, casings from cartridges, bright feathers, many different tracks. On the wet mountainous soil the tracks don’t disappear for a long time… Each village could create its own regional museum, completely unlike the neighboring one, but you would succeed in feeling the difference very, very slowly. When I listened to shepherds playing on the jews-harp [drimba]. a string that they press in their lips and strike with their fingers, for a long time I couldn’t tell a sad motif from a happy one. That hurt the Gutsuls very much. And only with time did I succeed in figuring out or catching something.

We understood very soon that any cinematic imitation, any stylization—like the way that ancient Russia, ancient Rome, or ancient Egypt is often recreated—would be offensive here. And that involuntarily impelled us to an understanding of what was most important and most necessary: the Gutsul as a person…

Once we had the fortune to live several days next door to a famous old lady. No one knew how old she was—they said more than a hundred. She didn’t object… We were brought up and introduced to her… The old lady remembered Ivan Franko [Ukrainian writer of the turn of the century]: she had gone picking mushrooms with him. He had given her French perfume, and to this day she had saved it.

I dressed my actor “national-style” and brought him to show her. Johnny [Vania] Mikolaichuk comes from these mountains and easily transforms himself, entering into the role. He looks remarkably handsome, to a rare degree, as if he had been deliberately invented for this jacket with a border, this hat with grouse feathers… I brought him into the hut. “Mammy Aliona! Look here: it’s Dovbush. Oleksa Dovbush…” [a Gutsul national hero].

Time had stopped for her long ago. She attentively looked at Ivan, then turned away. “But you’re kidding, sir! When I came to this place, a Jewish tavern stood here. And Dovbush’s horsemen came to me. I know what he looks like. Dovbush is lame and hunchbacked, he has kind eyes…”

Truly simple and holy. For her Dovbush was the embodiment of kindness—in other words, humaneness—but not of handsomeness at all. She looked not at the clothes (they could have been completely modern), but into the eyes… We had lived a long time in Gutsulia, we had admired its people just the same as we had admired its nature—without seeing their eyes, without understanding their inner harmony. And suddenly I once happened to spot something that… without searching for a word… was sacred—you couldn’t call it anything else.

In the cool morning, a bit earlier than usual, I left the hut and turned toward the precipice… In the icy waters of the Cheremosh there stood, concealed up to the chest, He and She. A middle-aged married couple. They were standing almost motionless, without removing their hats, and with dark, emaciated hands rubbed their unusually white bodies. The world for a second appeared in all its primeval manliness and nakedness.

I recalled the gift watches that present-day Gutsuls wear so proudly. I was reminded of history. Under Francis Joseph [Emperor of Austro-Hungary until his death in 1916], the Carpathians were often visited by well-fixed tourists, lovers of folk exotica, and the Gutsuls willingly gave up their beautiful embroideries, decorative vessels and plaques for glass beads, copper city bracelets, cheap trinkets… And it wasn’t strange later to see a lad whose hat brightly glittered with a golden epaulet instead of grouse feathers. And a policeman whom we encountered in the mountains didn’t look at all strange either. He had a surprisingly local complexion [dark], and in addition the brim of his cap was adorned with a downy mountain Indian-pink flower.

To this day these people perceive their world freshly as a child does—as if it were the only possible one. And they themselves—just as they are—are the “only possible ones” in this unusual world. Everything created by them is suggested by nature and at once almost blends in with nature. Their wooden churches, made from mountain pine [smereka], are inseparable from the architecture of forests and mountains; the voices of their horns [trembitas] are the result of the echo that is somewhat unusual on the pastures [poloninas].

We once happened onto a Gutsul funeral. I was amazed at first—the Gutsuls didn ‘t know how to hold a shovel. They were digging the small hole as helplessly as could be. They awkwardly turned over the dirt, mis-shoveling every minute, then filled it in unevenly.

But it was worth taking a look at the agility with which they operate rafts on rapid streams, catch loose logs, inlay walls, and chop out huts. In one short night they restored a suspension bridge that had been completely carried away during a flood. For that reason they have so many songs about the ax, so many legends about it.

Their fusion with nature and their originality have not been killed by history. The Uniat Church [combination Orthodox-Catholic]. which was once forced upon them, with its baroque decorativeness, is hostile to the nature of the Gutsul. They haven’t renounced their pagan holidays: they greet spring, bid winter goodbye, festively mark the first departure of the sheep for pasture. The Gutsuls have gone through sufferings and have themselves experienced everything that fell the lot of my Ivan Paliichuk: servitude, solitude, humiliation. But nonetheless they have remained free—as you see them even today. And we wanted to make a film about a free man, about a Danko of this earth (Kotsiubinsky liked the young Gorky very much [one of whose early stories featured a legendary hero Danko])—about a heart that wants to burst, to free itself of the daily grind : from petty passions and habits, wants to deliver the body and the soul from them. This is a poet, who once lost his muse and is fated to live, not understood and not understanding…

Shadows of Forgotten Ancestors (Sergei Parajanov, 1965)

ITtwas Sunday. All dressed up, the villagers crowded at the Temple of Our Lady. Here, too, came some hucksters, bringing their Sunday merchandise onto the square. One of them, a somber Gutsul, dumped a huge bag onto the ground and opened it. In the bag were toy flutes. Country women, weighed down with children, came up to the bag and each bought several items, which they shoved into the mouths of the babies and older children. Soon the whole square resounded with a drawn-out, discordant howling…

A boy came up to the bag, pulled out a flute. quietly played it… and put it back in the bag. Took out another… again blew, turning slightly aside … and again put it back. The bag’s owner cast a sidewise frown at the top of his head. The boy picked out one more whistle… played it again… and already was reaching for the next one, but here the owner tore the merchandise out of his hand, threw it into the bag and shoved him roughly away with his elbow. The boy took a few dragging steps, stopped not far away, and for a long, long time looked at the merchant with calm, grownup eyes. And round about there groaned, buzzed, howled, and squished a many-voiced chorus of artificial-sounding flutes.

***

Ivan does not have the occasion to die together with his beloved. He remains on the earth—and even experiences a degrading, carnal love for another woman. But the poetry living in him cannot be reconciled with this. He wants a kind and creative passion—one that dawns upon man like inspiration or paradise. He wants intimacy and oneness with his beloved. Like Romeo, or Tristan, or Ferhad. And therefore salvation for Ivan is in death, in non-being. Only there, beyond the bound of presence, does he see the possibility of fusing with his love and muse. A similar motif was born among many peoples, and this theme, of course, has an international resonance. We tried to reveal the Carpathians for ourselves, not as ethnographic material. Love, despair, solitude, death—these are the frescoes from the legend of a man that we were trying to create. I was not surprised that the film, made as it was on very individual material, was well understood abroad—by the Spanish, the French, and in Latin America. Among all the possible souvenirs that I got in the Carpathians, there are several home icons—typical handicraft work. Religious cartoons. Depictions of the saints, very similar to playing-card queens and jacks… Once, about seventeen years ago, they were exhibited in all local museums. Then they fell under someone’s “high wrath”: a little campaign was started. The icons were smashed with hammers, burned up and thrown out. Now you can hardly find them even in the villages. Recently I was visited by a French artist who had come over with an exhibition. He saw the icons and became unusually animated. “Oh, you know, in our country these ‘Spanish primitives’ are also very popular. Friends brought us some pieces from Spain, but much, much worse ones…”

***

We really deviated from Kotsiubinsky in some places—and, most likely, couldn’t have done otherwise. We wanted to penetrate to the depth, to the sources of the novelette, to that element that gave rise to it. We intentionally gave ourselves up to the material, its rhythm and style, so that the literature, history, ethnography and philosophy would fuse into a single cinematic image, a single act. We wanted to convey the feel of time, for we saw the nature and people of Gutsulia a hundred years later than Kotsiubinsky did.

But the force of inertia is surprising. Even after going to the depth, even after reaching, it would seem, the bottom, we still began shooting in a way that was somehow very operatic, very traditional. “Movie” thinking, which was alien to the material, constantly came back to our minds. All the time we wanted to edit nature. But, fortunately, the Gutsuls who appeared in our picture themselves would not let us skip on the surface. They demanded absolute truth. Any falsity, any inaccuracy hurt them. They clothed themselves after finding out first what would be shooting. They were offended when they saw a manicure on an actress ‘ fingers or an alien detail in a costume. We brought them to the studio to record their playing on the horns [trembitas], but they refused to play until they had put on their clothing and attached fresh flowers to their horns.

I remember we were rehearsing the scene of the funeral of Peter Paliichuk, Ivan’s father. The coffin was set up and the Gutsuls were asked to carry out the prescribed ritual. The empty coffin did not provoke any desire in them to carry out our request. We laid a man in the coffin. The Gutsuls said nothing. “Why don’t you say sumthin’?” “He ain’t Petro, he’s Mihailo!” So I “get” Peter… “Nope, this un’s a very bad fella. No suh! “But time is passing. Finally the tractor driver Peter, just having gotten off work, lies down in the coffin—folds his hands, closes his eyes… And a mournful wail, seizing you by the throat, resounds over the meadow. “ Oh, Petey! Petey!…”

Shadows of Forgotten Ancestors (Sergei Parajanov, 1965)

We wanted to make a film about passions understandable to every person, and tried to convey these passions in a word, a melody, in every tangible thing. And, of course, in color. And here I really relied on painting, for painting has long since, and to perfection, mastered the dramaturgy of color—its organization, the possibilities of bringing it out. It seems to me that to refuse to use color now would mean to sign knowingly a confession of your own weakness. Literal colorlessness to some extent means also figurative colorlessness. We filmmakers must learn today from such mentors as Breughel, Arhipov, Nesterov, Korin, Leger, Rivera, from the Primitivists—for them color was not only a mood, a supplementary emotion, but a part of the content. It is essentially a question of all visual culture, which it is silly to regard as some kind of dressing-up or decoration, but which in itself has content and ideology.

I once read a beautiful episode from the life of Delacroix that is generally well known. A certain lady suggested to him a subject for a painting: the Duke of Wellington, apart. talking with Prince Metternich. She had observed this scene in an embassy. Delacroix, after making a bow, objected—“… for a real artist that was only a blue spot beside a red spot.” And the same Delacroix, when he was asked what object he had wanted to depict in the hands of a soldier, answered, “I wanted to draw the glitter of a sword.”

Not a sword, but the glitter of a sword. But. it goes without saying, it is not so easy to find such a form which has its own content. The artist, of course, needed to depict not just two different spots, red and blue, but two concrete spots, the only ones of their kind; not just glitter, but the glitter of a sword. Undoubtedly he would have depicted differently the glitter of a gun barrel, of glass, or of dew. We are supposed to recognize something both in these spots and in this glitter. That’s the main thing. Of course, it would have been simpler to draw (or rather, copy) a sword, but who would believe in it? In a drawn sword or in drawn generals?

***

We impoverish ourselves by thinking only in film categories. Therefore I constantly take up my paintbrush, therefore I prefer to associate with artists and composers rather than with colleagues in my own profession. Another system of thinking, different methods of perception and reflection of life are opened up to me. That’s when you feel that the cinema is a synthetic art. It is one of the opportunities to get away from yourself, from your successes and mistakes, to get away from the standard, from the established and habitual world…

I once saw a country woman whitewashing a stove, and along with it a very good, colorful fresco. And thus she did every spring, not at all worried about the previous drawing . Knowing that a new one would appear, in no way worse. If this is an allegory, then not at all of the ease of self-renunciation, but of its necessity.

Now Shadows of Our Forgotten Ancestors for me has become a world that must be left behind . Something I will take with me, but more, most likely, I will abandon… I am now to treat a new, purely urban theme.

I have long dreamed of shooting a film about Kiev. Kiev has already been on the screen more than once: historical, landscape-like, architectural, industrial, destroyed by war. But almost no one has looked into the soul of Kiev, or noticed its sorrow and desires, or noticed its humanity. There is the new and the ancient Kiev. And it is one and the same city. A city that with each generation acquires new beauty, without losing the old. The biography of modern Kiev is unthinkable without its childhood . And for that reason I so want to make a film about time—the great architect. who constantly reconstructs, restores, destroys, builds up.

Time is generous and just—it removes the flights of history and returns us to the primeval truth. It cleanses the memory, removes calumnies and insults from the condemned, resurrects the forgotten, judges the unjust.

…In a neighboring courtyard, one of the courtyards of my childhood, a scraping sound begins at four in the morning. An old potter is starting his “wheel”… One after another, clay twins are released from his hands. He hardly looks at the form, whistles something through his nose. His fingers slide habitually and in differently over the clay, straightening the future sides…

But here comes a new order. The old man runs the circle carefully, slowly. He stops every minute. Looks, get used to the unaccustomed outlines. The fingers anxiously feel the composition. Now he is crossing over, stepping across something… going farther and farther away… The new object is set up on the bench, immediately changing the whole surrounding landscape. Another puddle, another tree, other clouds, mountains, the sea… And this whole limitless, generous world.

Shadows of Our Forgotten Ancestors was produced by Dovzhenko Studios, Kiev, in 1964; directed by Parajanov, from a screenplay by Parajanov and Ivan Chen dey, from a novel by M. Kotsiubinsky; photography by Victor lIyenko; art direction by I. Lakovsky and F. Yakutovic; music by Y. Skorik; principal performers, Ivan Nikolaichuk, Larisa Kadochnikova, Tatiana Bestaeva, Spartak Barashvili; 100 minutes; Magicolor; Prize for best production, Mar del Plata Festival, 1965; participation also in San Francisco Festival , 1965, and Montreal Festival, 1966; distributed in the U.S. by Artkino Pictures.